Within guitar culture, some individuals achieve legendary status but somehow remain under the radar.

Examples may include the elusive pickup maker and guitar builder ‘Over The Pond Guy’, renowned restorer Clive Brown, the late Les Paul replica builder known as Terry Morgan, and amplifier designer Howard Dumble.

These aren’t the type of people who engage with social media or even have websites, and a common phrase used in relation to them is ‘if you know, you know’. Most don’t – and a low profile combined with a high reputation and a shortage of solid information tends to foment fable and intrigue.

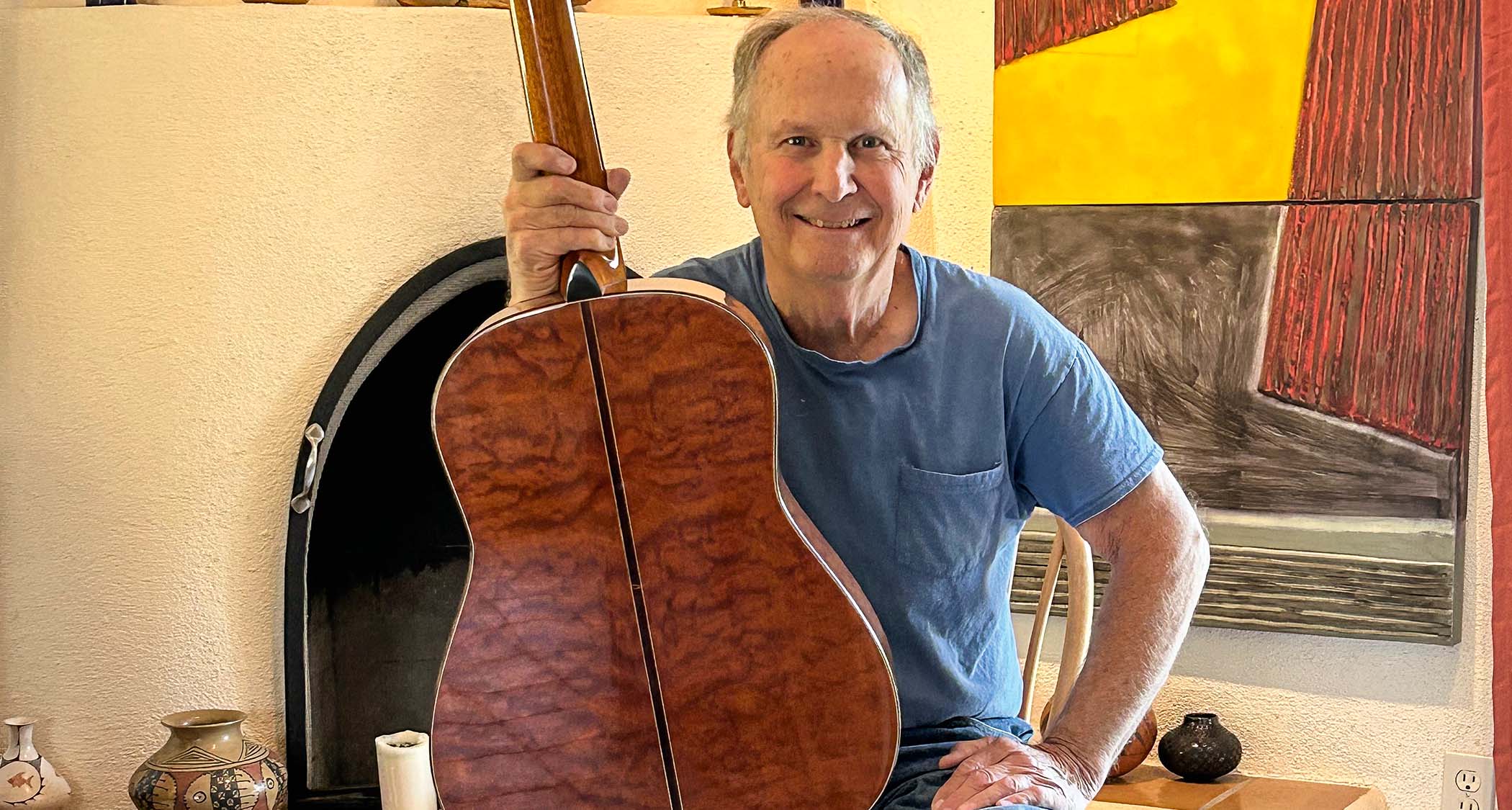

In the US, there’s a renowned acoustic guitar maker who fits this profile and his name is Don Musser. He doesn’t have a website and never advertises, but since the mid-1970s he has been quietly building guitars played by the likes of Bob Dylan, Tom Petty, Neil Young and even Eddie Van Halen. When the idea of a feature article was first mooted, we hadn’t even anticipated being able to talk to Don in person.

More in hope than expectation, we contacted Dream Guitars in North Carolina to ask if they could put us in touch and shortly afterwards we received an email from Don himself including his phone number and an invitation to call any time. Needless to say, we took Don up on his offer and found him to be friendly, forthcoming and fascinating.

The Backstory

Naturally, we wanted to know Don’s background as a luthier and guitarist. “My dad used to make replicas of early Colt firearms and he was a master machinist and a do-it-all wizard,” Don recalls. “He had a workshop with an incredible amount of tools and he quickly noticed that he could set me a task and I had the ability and dexterity to execute it. That’s where my interest in handwork and machine-level precision came from.

“I didn’t get interested in guitars until I went into the army in the early 1970s,” Don continues. “Fortunately, I wasn’t sent to Vietnam and instead I was assigned to Germany, and in the last six months I was there I started to learn to play the guitar. When I got home to Reseda [Los Angeles] I wanted to buy a 12-string, so I went to a store downtown that had a Martin. As I was trying the guitar, I flipped it over and sighted along the backstrip and the neck and I noticed it was a bit off centre.”

“It was a fine guitar, but my machinist eyeball led me to wonder if there were any custom makers who could perform every aspect of the construction with more precision.

“I looked in the phonebook and found the name Mark Whitebook, so I visited his workshop and placed an order. I pestered him a bit too much with visits and questions, and eventually he told me he was refunding my deposit and it would be a good idea if I built my own guitar.”

Without internet guides and books to help, we ask how Don set about the task.

“To build a guitar all by yourself is a daunting task because there are so many stages and there’s so much to learn about the woods” he points out. “I was really fortunate because Mark shared a workshop with another luthier called David Russell Young in a shop down in Topanga Canyon, and they were marketing their guitars through a shop called Westwood Music.

“They were getting a lot of success with very prominent musicians like James Taylor, Gram Parsons and The Stones.

“David lived around the corner from me and he wrote a book on building custom acoustic guitars [The Steel String Guitar: Construction And Repair]. I learned a lot from him and another builder called Roy Noble, and they were really agreeable for someone who wanted to pick their brains.

“I got that first 12-string guitar together, but it was not a marketable instrument and I knew I had a way to go. After another two or three guitars I felt I had got the finishing and playability down and I took a couple of guitars down to McCabe’s Guitar Shop in Santa Monica.

“I looked at a Martin on the wall there that was retailing for $1,000 and to make 100 per cent profit I offered them my guitars for $500 each. They didn’t even blink and they bought them and then sold both within a week. One went to Peter Fonda and the other to Tom Rush, who toured with that guitar for the next three decades.”

Although Don was only a semester away from graduating in chemistry, he quit college to concentrate on guitar building. He’s refined his methods over the years, but many of the things he still does came from his early mentors David Russell Young and Mark Whitebook.

Braces, Finishes & Glues

“On my guitars the top braces are radiused, rather than flat, so my tops end up domed. This withstands string tension better and it’s a stronger construction method,” Don insists.

“Another critical thing is humidity control. If you glue braces to a top at 40 to 50 per cent and then let the humidity rise to 70 per cent before glueing the top to the sides, you’ll have problems.”

We wonder if Don has some special bracing method. “I’m still doing a basic X-brace,” he assures us, “and having experimented with scalloped bracing early on, I realised I didn’t care for that. I like the notion of the top as a diaphragm, so the flexibility needs to be a little bit greater.

“I taper my braces and I use another little brace behind the bridge plate because one of the problems with factory-made guitars is that they belly and some of the string tension is dissipated into deforming the top.

“Supporting braces for the brace just above the soundhole are glued onto the sides. That was one of David Russell Young’s innovations and I always liked it because of the leverage of the neck under tension around the 20th fret. Having a fairly substantial brace there that’s linked into the sides of the guitar counteracts the leverage that can deform the top. I’ve found that anything you can do to make the neck less flexible produces more sound and enhances the sustain of an instrument.”

I have always done nitrocellulose lacquer. A lot of people have gone to all kinds of exotic finishes, but they’re hard to touch up and difficult to use

Don has refreshingly straightforward preferences for adhesives, too. “I’ve always been real trusting of aliphatic resin glue, and for some things, such as inlay, I might use epoxy, but for wood on wood it’s Titebond Original. I used to use epoxy to glue steel reinforcement rods into necks, but I’ve been fitting adjustable truss rods since around 2000 when I started selling guitars in Japan. They have extremely dry winters and a very moist rainy season, and this causes neck fluctuations, and the top and back will shrink and swell.”

As for finishes, Don prefers to keep things old-school. “I have always done nitrocellulose lacquer. A lot of people have gone to all kinds of exotic finishes, but they’re hard to touch up and difficult to use for one reason or another. I’ve been very protective of my health and always used a respirator. I’m 75 now and I haven’t suffered any consequences.”

Timber Tales

Don has spent periods as a timber merchant to the guitar-making industry, and a couple of finds have been particularly significant.

“Back in the 1980s I was living in Northern California and I was contacted by the partner of a woman who lived in Reno, Nevada. She had a stash of Brazilian rosewood imported in 1948 that was of incredible quality. The top dollar then was $40 per board foot and people had been offering her $10.

“When I walked in and saw the quality I said, ‘$40, no problem.’ I sawed it up and sold some of it, but I kept the best stuff. To this day I still have some of that wood and I’m looking forward to making more guitars from it. I was also able to purchase several quilted mahogany boards that were cut from a Honduras mahogany tree that has become so legendary it’s known as ‘The Tree’.”

Moving Forward

We can’t help wondering if retirement is on the horizon, but Don clearly still has the lutherie bug.

If somebody wants one of my guitars, Norm’s Rare Guitars and Dream Guitars usually have some in stock

“These days I’m still making guitars on commission, but I’m also selling guitars that I build for my own interest and enjoyment,” he tells us. “I used to make eight to 12 per year, but these days it’s more like five or six and I’m slower and more deliberate. If anything bothers me, I’ll just redo it. I’ve always been perfectionistic and now that I don’t have financial pressures, I’m even more so.

“I’ve got some things in the back of my mind for next year. I have a couple of necks from ‘The Tree’ and I want to use those for some guitars with quilted mahogany tops from the same tree. I have never built one of those mahogany-topped guitars before. If somebody wants one of my guitars, Norm’s Rare Guitars and Dream Guitars usually have some in stock, or they can contact me directly.”

- To get in touch with Don, use the following details: dmussergtrs@yahoo.com / 001 575 388 4804