As frontman with occult metal pioneers Mercyful Fate and, later, as a solo artist, King Diamond is one of the most influential musicians of the last four decades. In 2016, the Danish singer looked back on supernatural encounters, near-death experiences, Metallica’s approval and run-ins with Gene Simmons.

February 1984. It’s a freezing night in Copenhagen, Denmark. Under heavy snow, the streets are silent. In a rooftop apartment, something weird is going down.

King Diamond, the singer with Danish heavy metal band Mercyful Fate, is entertaining four guests: Timi Hansen, the band’s bassist, and his girlfriend, and Metallica’s Lars Ulrich and James Hetfield, who are in Copenhagen to record their group’s second album, Ride The Lightning. It’s been a long night, and all of them are drunk. For hours they’ve been sitting in the living room, talking and soaking up the heavy vibes from old records by Deep Purple, Black Sabbath and Blue Öyster Cult. In one corner of the room is an altar: a table draped in a black cloth, lit by tall candles and decorated with a figurine of the pagan idol Baphomet and occult books The Satanic Bible and The Necronomicon, the centerpiece a human skull.

King Diamond is an avowed Satanist. His obsession with the dark arts is expressed in Mercyful Fate’s songs and in his theatrical image: his face painted white and black, like Kiss, but with an inverted cross between his eyes. This occult shtick is of no interest to Hetfield and Ulrich, they just like the guy and love his band. But what is about to happens on this night at King’s place scares the shit out of Hansen and his girlfriend.

“I remember it clearly,” King Diamond says now. “At one point we left Timi and the girl alone in the living room, to have some fun. Lars and James and I went to my bedroom to play a game of table football. And then we heard a gigantic bang. I rushed back into the living room and both Timi and the girl were sitting there with faces white as sheets. Everything from my altar was spread across the floor. Timi said he’d felt himself being lifted up and thrown back down.

“I said: ‘It’s them. Don’t worry.’ I put the things back, and it was fine. But then the girl went off to the bathroom. After a while we could hear her crying in there. And then she screamed out: ‘Something’s growling at me! I can’t get out – the door’s locked!’ I took the handle and opened the door. She was sitting there in tears, dumbstruck.”

As King remembers it, Lars and James were too drunk to really absorb what had happened. But he was certain. “It was a visitation,” he says. “You could hear how they left – out through the bathroom window.” And he claims it was one of many such occurrences. “There were other experiences I had in that place. I remember once I felt a touch on my cheek… That place was haunted. So many people experienced stuff in there, not just me.

“In my life I’ve seen a lot of things,” he says. “Supernatural things. I’ve seen the place between heaven and hell.”

In his long career, both with Mercyful Fate and as leader of the band in his own name, King Diamond has remained a divisive figure. To some he’s a cult hero, a master of theatrical heavy metal, innovative and influential. To others he’s no more than a clown, a Halloween bogeyman with a singing voice like Rob Halford being boiled alive. What is certain is that he is a survivor. Not only a survivor of more than 30 years in the music business, but also a survivor of multiple heart attacks that almost killed him in 2010.

At the time when Mercyful Fate rose to prominence in the mid-80s there were many heavy metal acts with an over-the-top image. There was Venom, the original, devil-worshipping black metal band; Manowar, muscle-bound warriors from New York declaring ‘Death to false metal’; Thor, a former bodybuilding champion from Canada, whose stage act included breaking concrete blocks on his chest.

King Diamond appeared as much a caricature as any of them. With his masked face and satanic songs rendered in that mock-operatic shriek, he was frequently ridiculed in the music press. And yet there was something that set him and Mercyful Fate apart from bands such as Venom and Slayer, who posed as Satanists purely for shock value. King Diamond was entirely serious about this stuff. He was a scholar in the dark arts, and a member of the Church Of Satan, the organisation led by Anton Szandor LaVey, author of The Satanic Bible. And in Mercyful Fate’s music there was a depth and power that went far beyond the primitive bludgeoning of Venom and early Slayer. The band’s style of complex, heavy riffing was an inspiration to James Hetfield, who has stated that “Mercyful Fate was a huge influence on Metallica”.

Over the years there have been hard times for King Diamond. In 1984, in an interview with Kerrang!, he was branded a hokey Satanist, a fraud. Later came rumours that he was going to be sued by Kiss for infringement of their image rights. For long periods his brand of music was out of sync with the changing times, but through it all he has retained a loyal cult following and has continued to tour and make albums both with his own band and in a number of reunions with Mercyful Fate.

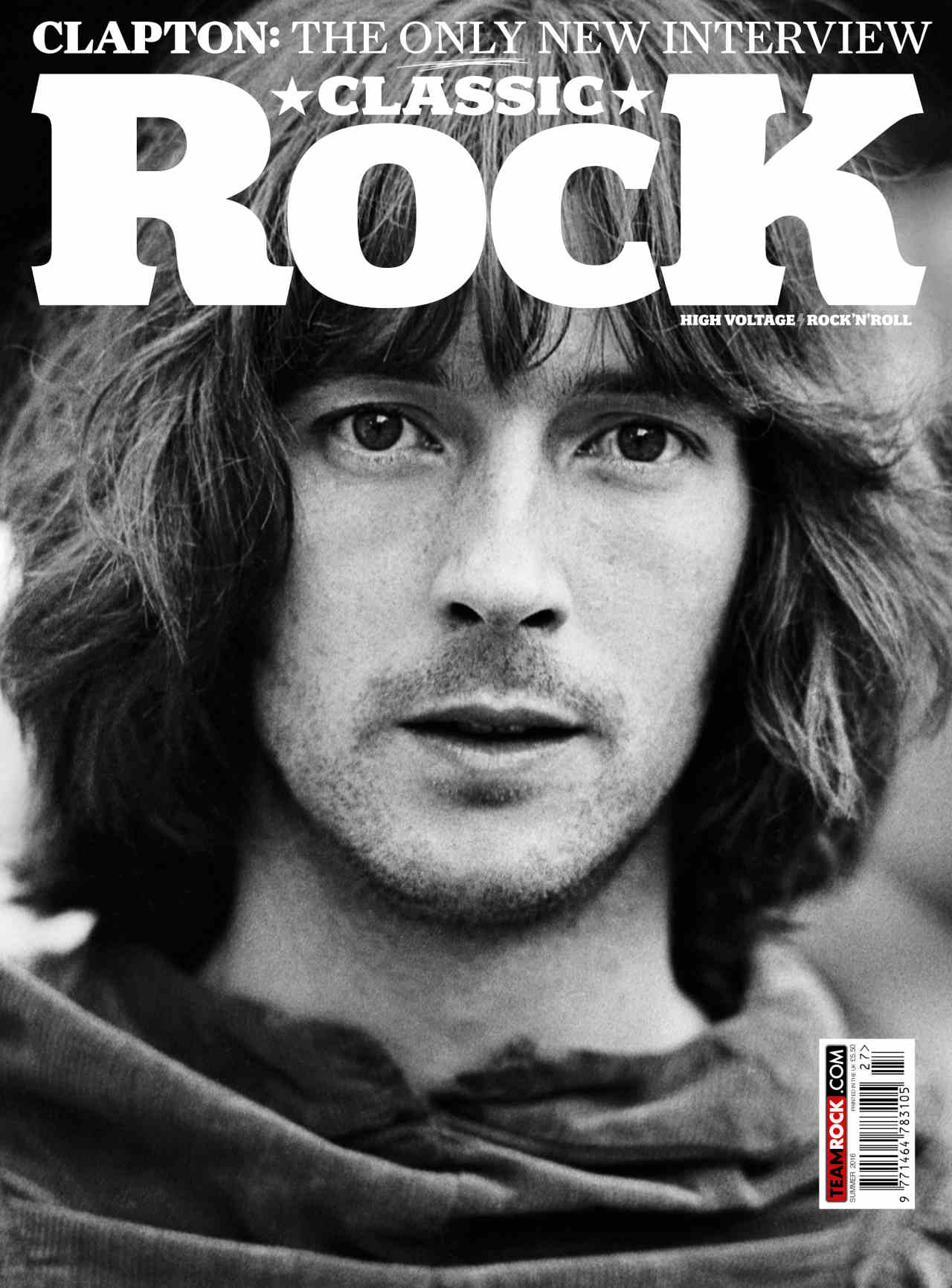

When he speaks to Classic Rock at his home in Texas he is in buoyant mood. “Right now things are good for me,” he says. The years he has spent living in America have softened his Danish accent. In talking about his life and career, our conversation extends to more than two hours. And he begins at the point of transformation – the moment when a bright working-class boy called Kim Bendix Petersen was set on the path to becoming spooky satanic rock screamer King Diamond.

It was in 1970 that the path opened up, when 13 year-old Kim heard a sound that would change his life – the sound that Jimmy Page conjured from his guitar in the solo on Led Zeppelin’s Dazed And Confused. “I was mesmerised by the way that music danced around,” King says now. “It was mind-blowing.”

He had what he describes as “a very normal childhood”. He was born on June 14, 1956 in Hvidovre, a suburb of Copenhagen. His father worked as a foreman at a storage facility, his mother was secretary to the city’s mayor. He had one brother, Viggo, a year older. There was strict discipline in the way the boys were raised, but “nothing religious whatsoever”.

What drew him to the dark side was not rebellion, but a curiosity informed by Black Sabbath albums and what he read about Jimmy Page’s interest in the infamous occultist Aleister Crowley. This led eventually to the work of Anton LaVey. “When I read The Satanic Bible,” he recalls, “it presented to me a life philosophy. It doesn’t tell you that you must believe in a god, it’s about the power of the unknown – which is the best word for these things that I believe in.”

What also had a profound effect on him were two rock concerts he attended in Copenhagen in 1975. The first was Genesis, on their final tour with singer Peter Gabriel. “It was a very visual show,” he recalls, “with Gabriel in his different costumes and make-up. I was bombarded with emotions.” The other concert was Alice Cooper on the spectacular Welcome To My Nightmare tour. “I was right at the front, and I felt that if I could have reached up and touched Alice’s boot then – pfft! – he would disappear into thin air. It seemed so unreal.” Entranced by the larger-than-life personas of Gabriel and Alice, teenaged Kim Petersen said to himself: I want to do that.

His entry point was not as a singer, but as a guitarist in his first band, Brainstorm, who played generic heavy rock. On stage he wore make-up in basic, experimental designs. He also adopted the name King Diamond – of which, he says, there was “no significant meaning”. It was in his next band, Black Rose, that he was the singer. He discovered that he could scream like Rob Halford and Ian Gillan. “I had no idea what ‘falsetto’ was,” he says. “I’m not trained musically. All I knew was that this sound coming out of me was fantastic.”

In Black Rose, King’s make-up also became more defined. He had not yet developed as a songwriter and lyricist. Nor was he making money from the band. To earn a living he worked as a laboratory assistant at a medicine testing facility. He quit the day job after leaving Black Rose to join a band called Brats that had a major-label deal with CBS. Brats were a punk band, whose guitarist Hank Shermann dubbed himself Hank The Wank. Shermann was growing bored of punk, however, and wanted to play heavy metal. As did King. “I joined Brats on the condition that we wouldn’t play any more punk songs,” King says.

This new version of Brats didn’t last long. CBS hated their new heavy metal direction, and demanded a more commercial style of music. As a result, Shermann and King quit, along with the group’s second guitarist, Michael Denner, to form Mercyful Fate in 1981. Completing the line-up were bassist Timi Hansen and drummer Kim Ruzz. Their goal was simple: “We wanted to be the heaviest band in the world,” King says.

Influenced by Black Sabbath, Judas Priest, Yes, Jethro Tull and Uriah Heep, they created classically styled European metal with a progressive rock flavour. Their music had a dark aura. The stage was set for King Diamond to go deep into the mysteries of the occult.

“I read a ton of books about Satanism,” he says. “But that’s not the way you find the real knowledge. The first time I had an experience that I simply could not explain, I knew something was there, with us, to help and protect us. And those experiences were what I wrote about in Mercyful Fate.”

Mercyful Fate recorded their first demo tape in early 1982. At King’s apartment, he and his brother Viggo and Kim Ruzz opened a case of beer and listened to it for the first time. “Suddenly,” King says, “my brother’s glass – full of beer – rose about a foot in the air, then went down on to the coffee table. For two minutes nobody said anything. Then I said to other guys: ‘I know you both saw that.’ They nodded. It didn’t feel scary in any way, but it was very strange. It felt like someone was saying: ‘Hey, we’ll be with you.’”

A four-track EP, Mercyful Fate, released in late ’82, proved to be controversial. Despite King’s intellectual approach to Satanism, that EP was crudely sensationalist. In one song, jokingly titled Nuns Have No Fun, his lyrics were gleefully violent and profane. ‘Upon a cross a nun will be hanged/She will be raped by an evil man… C.U.N.T… That’s what you are…’ On its cover of was a sexualised image of a semi-naked nun being crucified.

“We didn’t set out to be shock rock,” King claims. “But for sure, that song, and that cover, were done to create a controversy.”

To that extent the plan worked. A Danish priest called for a ban on the record. What followed was a debate between King and the priest on a rock radio station. “The priest hated us,” King says. “He said we were filth, disgusting, that we corrupting the Danish youth.” But King had done his research. “I said: ‘Yeah, that cover depicts a nun being burnt at a cross. But that happened for real back during the Inquisition – and it was you guys who burnt non-believers. This is a drawing you’re freaking out over, but you did this to real people!”

There was no ban on Mercyful Fate. On the contrary, the EP made the band a leading name on the underground metal scene. A deal with new independent record company Roadrunner followed and Mercyful Fate’s debut album, Melissa, was released in 1983. Kerrang! writer Malcolm Dome proclaimed the album “a masterpiece”. Songs such as Evil and Curse Of The Pharaohs evoked vintage Black Sabbath. King’s esoteric lyrics and bizarre vocals created an eerie atmosphere. And at the heart of the album was Satan’s Fall, a monolithic, 10-minute track incorporating 16 different riffs.

The band’s second album, 1984’s Don’t Break The Oath, was so dark and heavy that Mercyful Fate held ground amid the onslaught of thrash metal. King’s stage act was also becoming more elaborate, with a mic-stand fashioned from human bones. “A thigh bone and a shin bone,” he says. “I got them from a doctor who taught biology.”

It was while promoting Don’t Break The Oath that King was called out as a fake in Kerrang!. But as he says: “That didn’t really harm us.” What led to the demise of Mercyful Fate was pressure from within. By 1985, Hank Shermann had grown tired of playing satanic rock, just as he had tired of punk. “We were writing for the third album and there was extreme disagreement,” King says. “Hank was listening to funk music – Mother’s Finest and stuff like that. He wanted to incorporate that into Mercyful Fate. But that is not what I feel inside.” King realised that a split was inevitable when Shermann turned up for a band rehearsal wearing a pink jogging suit. Shermann and the other three musicians formed a new band, Fate, playing commercial hard rock. King went to the opposite extreme.

King did not mourn Mercyful Fate. “I went beyond it,” he says. “As an artist, I went deeper.” For his King Diamond band he recruited a gifted guitar player, Andy LaRocque, and powerhouse drummer Mikkey Dee (who would later spend 20 years in Motörhead). The music was more ambitious than Mercyful Fate’s – as illustrated by Abigail, a concept album based on a horror story set in the 19th century.

This and subsequent albums were as grandiose and experimental as they were heavy. “We did have a very unique sound,” King says. “And it was very visual. We used so many instruments to create different moods: cello, violin, harpsichord, and the good old Hammond organ in the style of Deep Purple and Uriah Heep. That’s what created the atmosphere, the gothic feel, on those albums.”

Most important of all, King says, was what those albums represented in terms of his personal philosophy. “King Diamond [the band] is way more satanic than Mercyful Fate was ever close to,” he says. “In Mercyful Fate I was talking about myths and legends. King Diamond has the entire satanic philosophy – to the max. And mixed into that, my experiences of the occult.”

A defining moment for King came in 1988 when he was granted an audience with the man whose writing had done so much to shape that philosophy. During an US tour he visited The Satanic Bible author Anton LaVey in San Francisco.

“I got to spend an hour and a half with LaVey in the ritual chamber at the Church Of Satan,” he recalls. “I asked to be the first to talk when I met him. I didn’t want to be some little puppet nodding at what he said. I spoke first, so I could tell him what I feel. I talked for forty-five minutes, and when I finished he took his Baphomet symbol off his jacket and pressed it into my hand. That said everything to me.”

King declines to reveal exact details of his conversation with LaVey, and describes it only in broad terms. “I talked with him about life philosophy,” he says. “I know how serious he was about how he saw Satanism, what it meant to him, the master plan. Those were things he told me about. And it will never go further.” He later received a hand-written letter from LaVey. “It was amazing the things he wrote,” he says. “Really nice things. To this day I always carry that letter with me.”

It was also in 1988 that King was reportedly threatened with a lawsuit by Kiss. At that time Kiss had been out of make-up for six years. But, Kiss being Kiss, had their image trademarked. On his 1988 album Them, King had his face painted in a design that bore a strong resemblance to that used by Gene Simmons.

“They might have wanted to sue me,” he says. “But lots of people used make-up before Kiss, and they were not the ones that inspired me. It was Alice Cooper and Peter Gabriel. But I don’t hate Kiss; I still listen to them.” In the end the lawsuit never materialised. King believes he knows why. “I didn’t have much to be sued for,” he says, laughing.

For King – always by definition a cult act – there was never a fortune to be made. Black Sabbath, for all their devilry, had a zinging three-minute pop hit in Paranoid. Alice Cooper played the bogeyman, but had School’s Out. Even Metallica, King’s friends and former peers, would go mainstream with the Black Album. King, with his scary face and banshee wail, was never going to cross over.

What he has had instead is a successful career in the margins. Over the course of 30 years he’s had big-selling albums – Them sold 200,000 copies in the US. He also received what he calls “a nice bonus” in the late 90s from Metallica’s two-million-selling covers album Garage Inc., which included a medley of five classic Mercyful Fate songs. In that album’s sleeve notes, Lars Ulrich described the evil genius of Mercyful Fate: “They were doing this wild Purple-meets-Judas Priest thing with a more progressive element. Really insane stuff.”

Mercyful Fate also had a major influence, along with Venom, on the Norwegian black metal scene of the early 90s. Not only for their heavy music and satanic vibes, but also for King’s image, copied in the ‘corpse paint’ worn by bands such as Mayhem and Emperor, which defined the whole aesthetic of black metal. King acknowledges the influence that he and his band had on black metal, but he recalls his shock at the genre-related events in Norway in 1993: the burning of churches, and the brutal murder of Mayhem leader Oystein Aarseth by rival musician Varg Vikernes of Burzum. “These were sick, crazy, twisted things,” he says.

That leads him to address the great conundrum in his life. To distance himself, and Mercyful Fate, from the horrors of Norwegian black metal, he states: “I don’t think anyone could have misinterpreted what we were doing.” And yet in the very next moment he admits that he has been misunderstood for his entire adult life. “I’ve tried to explain this so many times,” he says. “People ask me: ‘Are you a Satanist?’ To answer, I have to ask them a question first: ‘What does that mean to you?’ If you think it’s someone who sacrifices animals, or worse, no. Are you insane? I would never harm an animal. If you think that’s it, you’re crazy.

“What I will say is that there are powers that I have experienced. What they are exactly, I don’t think anyone can say. That is why they are unknown. Nobody can prove that they believe in the only true god. It’s a matter of personal belief.”

King Diamond turns 60 this year, and feels lucky to be alive. In November 2010, following a series of heart attacks, he had triple-bypass heart surgery. He had been a heavy smoker since he was a teenager. “A pack a day. Now, I haven’t had a drag for more than five years.” Most days he power-walks for five miles. “I take nothing for granted,” he says. “I got a second chance and I’m grateful for it.”

He lives in Frisco, a suburb of Dallas, with his wife of 13 years, Livia Zita, a former singer, born in Hungary, and their two cats. “No kids,” he says. “Not yet. But I’ve not given up. It’s hard when you have the life I have, being away on tour so much. But I would love to see kids grow up.”

At this stage he is still contemplating a final Mercyful Fate reunion. “I will never say that it’s finished,” he says. “Hank and I still talk. He wants to do the Mercyful Fate masterpiece, as he calls it. I would love to do that too.” For the immediate future, King’s focus is on a new King Diamond album. He plans to start writing with Andy LaRocque later this year. It will be, in the classic King Diamond tradition, a concept album. And it will be recorded in his new home studio. “With no time restrictions,” he says. “I can do forty-part vocal choirs if I so desire. I can make everything perfect.”

His aim, in his words, is to make “the ultimate King Diamond album”. And in creating it he will have, he says, a little help from his friends. His home in sunny Texas is so far away from the apartment he left behind in Copenhagen all those years ago. But now, as then, King Diamond senses around him the power of the unknown. “In this house there are four hotspots,” he claims. “It’s not often that things happen, but they happen.”

They are, he says, still with him: Them

Originally published in Metal Hammer issue 225, June 2016