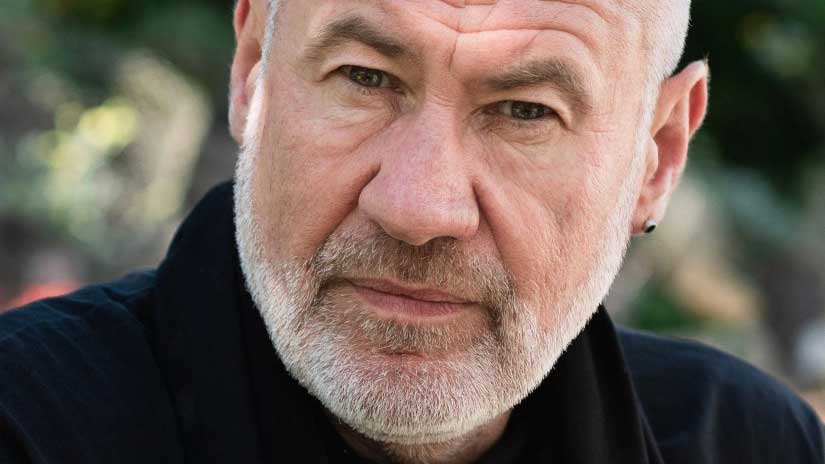

At the age of 66, Derek William Dick is still the same questioning, creative, bold-asbrass force of nature that he was at 22, when he moved from Edinburgh to Aylesbury and joined Marillion, and changed his name to Fish. He picked up the nickname as a teen because of his habit of spending hours in the bath, smoking cigarettes and singing along to his favourite rock music, which back then veered between Genesis and Pink Floyd.

Before Fish joined, Marillion were a mainly instrumental group whose love of complicated progressive rock was as yet unmatched by their ability to play their instruments. However, a 1980 demo did contain musical templates for Forgotten Sons, Garden Party and parts of The Web, as they became once Fish had written some lyrics and provided the Peter Gabriel-like vocals.

By the time their debut album Script For A Jester’s Tear was released in March 1983, Marillion had built up such a following that it leapt straight into the UK Top 10, bolstered by two hit singles: He Knows You Know and Garden Party. A year later to the very day, they did a similar thing with their second album, Fugazi, and two more Top 30 singles.

It was their third album, Misplaced Childhood, which went to No.1 in the UK in June 1985, that propelled Marillion to platinum status and Fish to a household name – loved by the tabloids for his unashamedly hedonistic lifestyle, but taunted like a bull by the typewriter matadors of the music press. The single Kayleigh went to No.2 in the UK and top 10 in several other countries, and follow-up Lavender did almost as well, hitting No.5 in the UK.

There was one final Fish-era album – their best yet, Clutching At Straws, in 1987, which reached No.2 in the UK. Marillion were now at their peak. Fêted in America, where Iron Maiden’s management offered to help them conquer the charts; adored by fanatical fans around the rest of the world; with a new publishing deal on the table for more than £1 million.

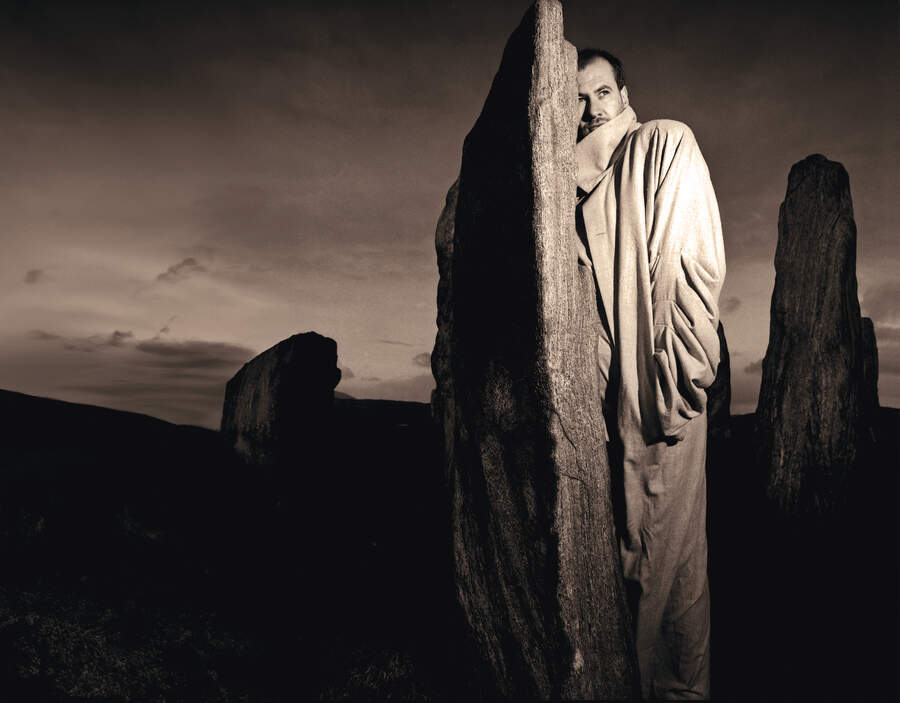

Then came the split. Fish walked out at the end of 1988, and returned to Scotland to build a new life as a solo artist. It began well, with his Marillion-like debut album Vigil In A Wilderness Of Mirrors in 1990, which made the top five in Britain and Germany. The follow-up, 1991’s Internal Exile, did not fare so well. A surprising mix of Gaelic folk and Celtic rhythms, it scraped the UK Top 20 then vanished.

There would be another nine solo albums of varying quality, from the cringe-fest of Songs From The Mirror, his half-good half-awful album of covers (Fish does T.Rex, anyone?), to his final and greatest album, Weltschmerz, in 2020. But no more hits, and only 1994’s excellent Suits making it into the Top 20 again.

This year sees the start of Fish’s official farewell tour and the re-release of remixed versions of Vigil and Internal. We have known each other for forty years, yet he always surprises me with what he has to say. He warns me: “I’m going to tell you right now, I am fucking bored with talking about music.”

Like all gentleman rockers of a certain vintage, however, we begin by discussing our various ailments. “At the moment I’m waiting on implants,” he says. He explains that when he had a bad tooth extracted recently the other teeth “all moved like gravestones in a swamp, they went all shoogly, moved to the side then the front.”

“Ooh, sounds nasty,” I say. But that’s just the start.

“I’ve got two replacement knees now. Had my shingles vaccination, my aortic aneurysm scan, then the bowel-check camera up the arse. The colonoscopy is lovely,” he deadpans.

But this is typical old-feller talk. More distressingly, he has also recently concluded that he is on the autism spectrum. “My wife Simone and I were both dealing with family issues where we were wondering why people were behaving a certain way. We started reading books on autism, Asperger’s syndrome, borderline personality disorder. I was going: ‘Wait a minute, I do that.’ That’s when I discovered that I was actually autistic, and I had no idea that I was before. I had managed to take all those issues and convert them into a way of life.”

This rings resoundingly true. The freak-outs over tiny details, the in-your-face personality, the seemingly impossible demands and behaviours. “You’ve seen me in this condition, I get very loud and aggressive. Not violent, but in an argument I will defend positions like crazy. I sit and think out every possible option, position, outcome, argument. Then I started to realise why I did that, because of the spectrum stuff. And that’s why I write so well, because everything I do, I find a lot easier to come to terms with if I put it down in words. It’s the only way I can reason it all out.”

So here we are once more…

On top of the farewell tour and your reissued albums, you sold your house and home studio this year and relocated to a croft on a remote Scottish island. Let’s start there. Why?

People say: “Why are you moving to this island?” Because the place where I live now, I’ve filled every nook and cranny, got every corner exactly how I wanted it. But now there’s no more building I can do. No more rooms, no more garden, no more orchard. I’m full. Up on the Croft, I have a huge blank canvas that I can do whatever I want on. I’m bored with the music business. I knew I’d done it in Weltschmerz. People were like: “How do you know it’s the last album?” Because I can’t take it any further.

Tell us more about your autism self-diagnosis. Mental and emotional instability are recurring themes in your work.

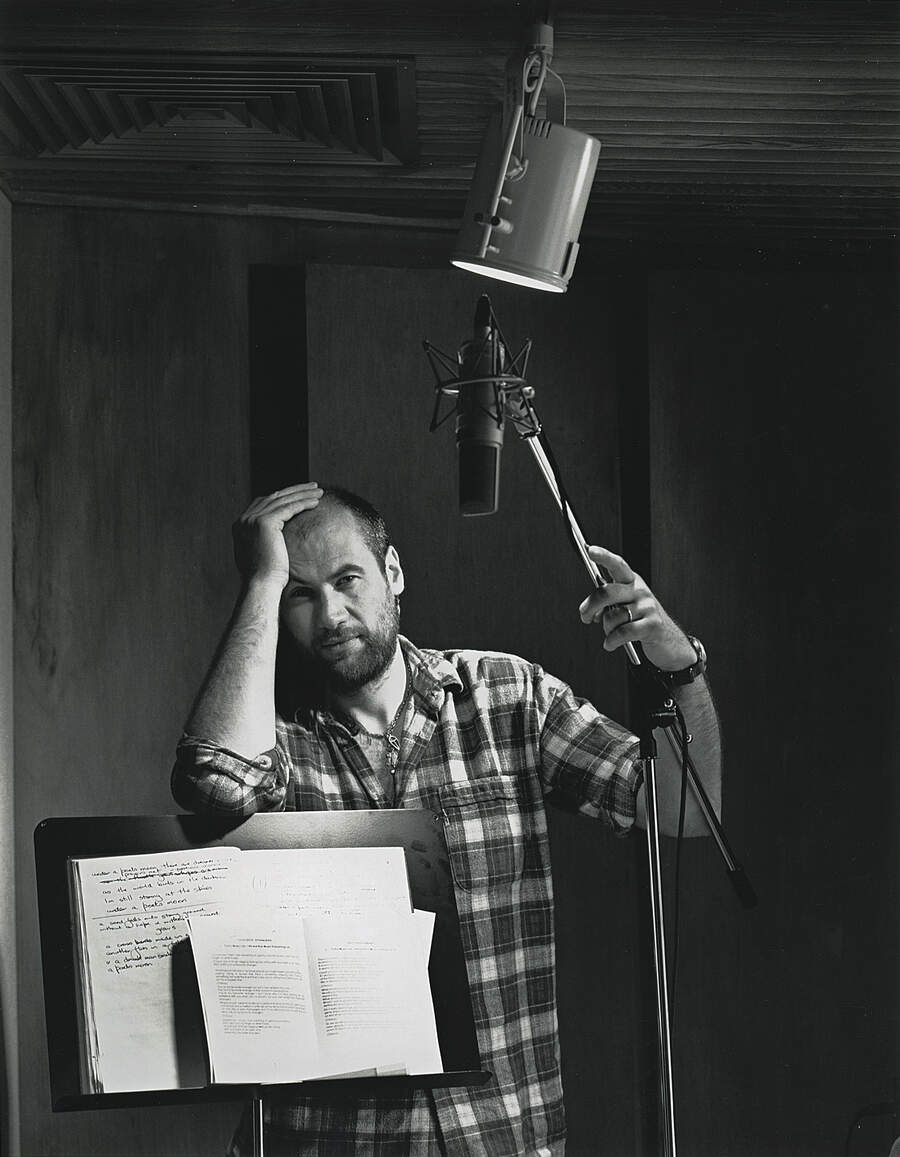

Yeah, exactly. I think people find it difficult to admit to depression. But everybody gets depressed. I’ve been very, very dark a few times, as we all know. But I deal with my black days in songs. There’s three levels of songs. The first level is your framework story. The second is your subconscious, what you’re trying to hide. Then your third level is the one that you discover way down the line.

A good example of that is Waverly Steps [the 13-minute-plus epic from Weltschmerz], which was about a homeless army veteran. He didn’t want to be institutionalised, so he stayed on the Waverly steps [the covered access to Edinburgh’s Waverley station]. When he died it made the papers, and I took that story and embellished it and created an entire character around it. Not an army person, but somebody that was suffering from chronic depression and had mental health issues and married the wrong person.

Then listening back one night, I went: “Fucking hell, that’s me!” I realised how much of myself I’d actually put in that lyric. I didn’t do it intentionally. It was third level. Again, that’s autistic as fuck. It came out of the blue, discovering I was on the spectrum, and there were parts of this new discovery, or this new sense of awareness, that got me down for a bit. Then it’s like, wait a minute, I’ve managed to make a career and a life out of mastering what some people see as a major problem. Because I didn’t know better. But once the curtain had been pulled back, I went: “I know why I do that now.”

That’s why I could shoot people in the head and walk away with no feeling whatsoever, because if you ain’t with us, you’re against us. It was my nature to deal with it and move forward and make it be successful. I left the band [Marillion] because I wasn’t allowed to do it any more. When we made Misplaced Childhood in Berlin, you and I sat in that hotel room near the studio, and you asked me about Kayleigh and I said: “It’s a hit. This is the big one.” And then we went on the road and it all started to happen.

That’s when the gang mentality started to break up, and then it was down to money. It was difficult to handle. Coming off stage and being faced with forty people you don’t know who all wanted to shake your hand. Then [the band] all started to move apart and it suddenly wasn’t a gang any more. You realise that people are only looking out for themselves.

You actually made Marillion cool: NME and the broadsheets covered you. After Kayleigh it was Blitz magazine and the tabloids. I recall us going to see David Bowie together at Wembley Stadium in 1987, and you were surrounded by your new best mates Tony Hadley and the boys from Spandau Ballet, and Roger Taylor and Brian May from Queen. But not Duran Duran, who I think you still considered satanic.

[Laughs] Yeah, well they were to me then! But Blitz magazine and the NME would want to interview me just to slag me off. I stood my ground. I was a target back then, but I could give back whatever the fuck they gave.

You weren’t uncomfortable in that company. And that really helped sell Marillion as more than just a retro prog band.

It’s strange. I heard some of the early stuff, when Marillion and I first got together, and I heard the energy from our Reading festival show [in 1983], and the attack, the energy, it was punk prog. There was a lot of venom. I think that’s why I made some friends along the way that you would not necessarily expect me to make, that had a certain amount of respect for the way I approach things. But I had to leave. I remember thinking at the time: “If I don’t leave I’m going to end up sitting in a fucking mansion with two Irish Wolfhounds, with a massive cocaine habit and drinking cognac until I was a bright blue flame in a crematorium.”

What prevented that happening?

I think a fuse blew. It was too easy to take the fucking money. And money never drove me. The one thing that really rankles me is [Marillion keyboard player] Mark Kelly saying I always wanted more money. “Fish wanted fifty per cent of the live thing,” he said. That’s bullshit. I didn’t want more money. What was getting to me was the people that were taking advantage of our better natures and especially my better nature.

I’d been naïve and caught out by giving money away, people I’ve been ripped off by because I trusted them. It hurt me when [Marillion drummer] Ian Mosley in his book basically implied that the only reason I had the band as best men at my wedding [in July ’87] was as a publicity exercise. The reason they were asked was because I thought they were my best friends.

There was a bus driver I had on one of my solo tours, he’d also driven the bus on some of the last Marillion shows I did. He said he’d overhear the band talking about who they were going to get to replace me. Nowadays I don’t fucking care, because the best thing I ever did in my life was to leave that band. I would not be the person I am now if I hadn’t left that band. Seriously.

Let’s talk about the new mixes of your albums Vigil and Internal Exile that you release later this month. Were you unhappy with the originals?

Not Vigil. But Internal was the very first album that was recorded here in my studio, and it didn’t work. It was a half-finished Rubik’s cube. [Scottish producer, keyboard player and long-time Fish collaborator] Calum Malcolm remixed it, and it is stunning. Incredible! Poets Moon and Carnival Man [originally bonus tracks on the remastered 1998 edition] have been moved inside the album and Lucky has been moved up, and the whole pace sits perfectly now.

When you first went solo and moved back up to Scotland, it seemed counter-intuitive at the time. Wouldn’t you have been better off career-wise moving closer to London, to be closer to the music business power base?

I would have fallen into a rabbit hole if I’d done that. I had to extricate myself, to rebalance myself. I would have been in danger of turning into that character in Incommunicado.

You mean the ‘rootin’-tootin’ cowboy’ with ‘an allergy to Perrier, daylight and responsibility’?

Yes. And I knew that. I’ve had to empty the attic here. Lo and behold, I came across the handwritten letter that I wrote and had photocopied and sent to the band. I found it very interesting to read as my present self. It was a classic example of autism-spectrum shit. Some of it was not great. But I wrote it after I sat and did a forty-four-ounce bottle of Jim Beam. I was so highly tuned into this problem that it was completely consuming me. I was fucking lost. I didn’t have any really good friends outside the band. I was completely adrift when I wrote that thing. I was lonely, I suppose.

So there was nothing else keeping me down there. On top of that, I knew if I stayed I was going to lose my marriage, and my marriage was the only thing I had left. If I’d been so money-orientated I would’ve stayed in the band, signed the million-pound publishing deal, taken a huge chunk of that away with me, and dealt with the fallout of that when I did leave the band. That was what the cold, calculating, smart machine would’ve done. I just went fuck it, I can’t deal with these guys any more. But I was busted. I was in Soho singing for M&Ms adverts, for two hundred pounds, because I had no money. They stopped my wages. It was like, sell the house, move up here.

Fish returns to the ‘Why leaving Marillion was a good thing’ thread throughout much of our conversation. Enough to let you know he’s thought about it ever since.

“I wouldn’t change anything from back then,” he insists repeatedly. “I have done so much outside the ranks of that band that I would never ever have accomplished.”

At the same time, he insists, “the person I was back then was really different. I was talking to Simone about this. We met years ago, but we finally got together in 2010. She said: “What would have happened if we’d met back in 1984?’ I said: “It wouldn’t have worked because I was a different guy.” I’ve had to evolve and mature. The guy that left the band in 1988 was a very different guy to who’s talking to you now. I was dangerously impetuous at times. But in the early days of a band, having that impetuosity is a positive thing.

“I’m a lot happier with myself now than I was back then. I’ve got thirteen sheep, a tractor, we’ve resurrected a twenty-five-year-old croft on a beautiful island. It’s myself and my wife, and we’ve got a lot of really good friends up there now. And that’s where I want to be. I’m not really interested in the old pizazz, razzmatazz.”

So no regrets, professionally?

I’m not a control freak, but I need to know what the fuck is happening. It’s difficult to talk about, because there were a lot of things that happened back then that I took very personally. Now I accept them. I get upset when people in their biographies start writing things about why I left the band, why I did this, how I did that. I’m freshly raw, because I’ve been writing up the Internal Exile and Vigil sleeve-notes – twelve thousand words each – and I’ve had to go back and think about it all again.

Your name popped up as well, right? I was writing about the Lockerbie charity show [in 1989], when you came up here to do the first ever interview I did as a solo artist. With Internal Exile, I say that I thought the ‘difficult second album’ syndrome only happened once in your career. I didn’t know that it applied to a solo career as well as a band career. I’d just come out of the Marillion litigation. I was building a studio. My first wife was pregnant. I was financially taking an absolute kicking, and I was trying to write an album.

Did you gain any new insights from writing those sleeve-notes?

I think if you put together Vigil and [the first Marillion album after Fish left] Seasons End, you would get what the next Marillion album would have been. I mean, Easter [from Season’s End] is a beautiful track. And I’m incredibly proud of Vigil. I am leaving behind a great collection of songs. It might not be that I sold anywhere near Taylor Swift’s numbers. I’ve not sold anywhere near Genesis’s numbers. I don’t give shit, because I’m proud of the songs I did. I’ll stand by them. They’re not all worldwide hits, but it’s a great collection of work and I’m really proud of it.

You’re bowing out in February next year with a show at the London Palladium. How do you think that is going to feel?

It’s going to be weird. My great grandfather was in the music hall, him and his brother, one a musician, the other a singer. That’s what Raw Meat [from 1994 album Suits] is about. That was inspired by my great grandfather. He would have loved to have played the Palladium, so one thing I definitely know is I’ll be playing Raw Meat at the Palladium.

Mid-September we start rehearsals for the farewell tour down near Redditch. Then we’ve got the European leg, and then we’re up to the croft to live permanently from mid-December through to February 2025. Then we’ve got the UK tour that takes in February, March. And in the middle of all that our thirteen ewe lambs will be starting to lamb, and our thirteen will hopefully become at least twenty-six.

The thirteen ewe lambs all have names – Heriot, Brownlie, Schaedler, Stanton, Black, Blackley, Edwards, O’Rourke, Gordon, Cropley, Duncan, Hamilton and Hazel – which is the full thirteen squad players of the famous [Eddie] Turnbull’s Tornadoes, the 1972 Hibernian football team that beat Celtic two-one in the Scottish League Cup that year.

Then I’ve got to sort out the potential licensing of my entire back catalogue, which will happen next year, and potentially a best-of album that might be coming out at the end of the year in the middle of all that and dealing with all the other shit. So I’ve got that. And I’ve still got to learn to drive a tractor.

I am so well-trained now. I feel like some sort of special forces officer, right? Simone and I both stopped drinking and smoking on the first of January this year. Because we both said there’s no way we are going to get through this year if we’re drinking. Even if we’re only drinking once a week.

Well, I’ve got to say, I’ve never seen you looking so well. You look relaxed, even without your teeth. When Shane McGowan died last year I thought of you. If you’d gone through door number two, as it were, that could have been you, couldn’t it?

You got it. I sold all my Marillion royalty streams. Which is like my pension. My royalties come in twice a year, every year. An American company came in and said we will buy all your royalties and give you ten, fifteen years’ worth [of royalties] at once. Not only did it pay for the croft, but because I pay my tax [in Scotland] a lot of the equipment I need for the croft is tax-deductible. I’m able to buy the tractors and all that stuff.

Maybe you should do a [Jeremy] Clarkson’s Farm and turn it into a reality TV show.

I turned down two offers from TV stations to do that. Because this really is going to be our sanctuary, it could be taken the wrong way by other crofters. You don’t want to be that guy. Instead what we are doing is spending a bucketload of money basically resurrecting the croft properly. The first thing we said to the people up there was it’s not a holiday home, this is a move, we’re taking it seriously. And the community’s taken us in, they understand.

Simone and I are creating something there that’s really special. And with everything going on, we should be able to retire. I wouldn’t say comfortably, but we can retire, and for four weeks a year, maybe, when it gets dark and shitty up there and the wind’s getting really high and we do like everybody else and leave the island for a while, I can do [his special fan shows] Fishheads Club, or I can do a stand-up show, or a reading tour where I take one of the episodes of the [still unfinished] autobiography. There’s a lot of things I can do. Simone says she’s never seen me so peaceful and so at ease as up there.

You’ll love this story. It was Simone’s birthday and we went out to a ceilidh [pronounced ‘kayleigh’]. I’d never been to one before. I thought it was just Highland dancing, but it’s a whole coming together, could be ten people, could be a hundred and ten people. It was near a beach. There was a band playing Runrig and Eagles songs and Highland dance music. Drinking whisky. There was a raffle with fucking farm gates as the prize. All in aid of the air ambulance service. The sense of community, the friendliness, the openness was just outstanding.

Then Simone and I were outside talking to a bunch of people. There was a girl there, I asked her name and she goes: “Kayleigh.” I said: “You’re kidding me. I’m meeting Kayleigh at a ceilidh?” I said: “Was your dad a Marillion fan?” She said: “No, my mother fancied the singer.” We were all laughing.

Fish’s Road To The Isle tour starts in October, with UK dates beginning on February 18. Fish’s first two solo albums are out now, and can be ordered from his webstore.