Stories about flawed young women have been favoured by the publishing industry for some time now. Bad Girl novels proliferated in the wake of Gone Girl and The Girl on the Train, while Sad Girl novels have evolved from the comic haplessness of Bridget Jones in the 1990s, to more sobering ground with Sally Rooney’s introspective bestsellers.

Sad Bad Girl novels combine the best – or should I say the worst? – elements of these narratives. Titles like My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh, Luster by Raven Leilani and Animal by Lisa Taddeo all feature disaffected or disturbed young women acting out, or wilfully sabotaging their lives.

Despite the impressive writing of authors such as Leilani, Moshfegh and Taddeo, too many of these stories fail to keep up with their own ideas. Trauma is sensationalised, damaged characters are diminished and complicated, and challenging situations are compressed into marketable entertainment. Sometimes this is alarming, but mostly it’s just disappointing. It also means the Sad Bad Girl was a trope from the outset.

Typically in her late 20s or early 30s, the Sad Bad Girl is insecure and adrift, seething with self doubt and drowning in denial. Her family is dysfunctional if not abusive, she drinks too much, makes terrible relationship choices, resents her boring job, and dreams of becoming a successful creative. Her friends, if she has any, act as sounding boards or barometers for her emotional messes. She is self-obsessed, self-serving and self-destructive, and I’m afraid I’ve had enough of her.

Read more: Friday essay: beyond 'girl gone mad melodrama' — reframing female anger in psychological thrillers

It’s not that I’ve had enough of stories about women. Far from it. As a writer, I have spent most of my career focused on female narratives. I have challenged the misrepresentation of women in the music industry, explored essentialist ideas about the female psyche and confronted the diminished antiheroine of thriller fiction.

But the one thread connecting my work is a call for more complex stories about psychologically nuanced women.

So as a reader, I’m cynical. I’m frustrated by the proliferation of stories about two-dimensional women behaving badly when there is such rich potential for transgressive Sad Bad Girls.

Green Dot’s lost millennial woman

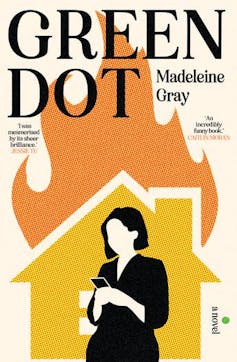

Unfortunately, the much-buzzed-about Australian debut novel, Green Dot, with its tale of a young, white, messed-up woman searching for meaning in all the wrong places, fails to break new ground.

If you haven’t already heard about Green Dot, you will. The buzz is growing and the book is set to be a huge summertime success. Sharply observed, funny and tender, set between Sydney and an unnamed British city, it’s a likeable enough narrative. Fans of Dolly Alderton will probably love it. But take a closer look at this frothy, sassy story and you might begin to question the appeal.

Put simply, Green Dot is the tale of an office love affair between 24-year-old Hera and Arthur, her older, married colleague. The unique pain and pull of first love is beautifully depicted at times, and Gray is a competent writer. “I am aware that a past version of myself, one who is not so embroiled, would likely see this all with much greater clarity,” thinks Hera, when she can’t get hold of Arthur. She reflects that the old Hera “would likely stick up for herself more, would find Arthur’s entitlement galling, or she would never wait around in the first place.”

But for much of the novel, the tone is trite and the characterisation, although astute, is patchy. While this starts out as a fun page-turner, by the midway mark the singular theme of Hera’s yearning for Arthur begins to weigh.

Conforming to the trope of lost millennial woman, Hera brims with fragile confidence and pernicious self-doubt. Disaffected, cynical, irreverent to the point of positively irritating, she inhabits her story with wit and humour. But her relentlessly interior perspective lacks self-reflection.

There is nothing much in the story to alleviate this. Hera’s friends, Soph and Sara, exist mainly to let the reader know Hera has friends with opinions about her behaviour. Other characters function mainly to witness Hera’s affair or remind her that she misses Arthur.

As for Arthur, a charmingly uncool intellectual from England, he is essentially a prize who offers Hera self-validation in the form of her own emotions. “What I really wanted was feelings to protect,” she confesses. “And here they were.”

Self-abasing ‘almost for the sake of it’

Long after her affair has run its course, Hera realises “my dedication to this relationship was in fact a dedication to my belief in myself”. Yet this declaration, which appears at the start of the story, doesn’t afford her any insight beyond the fact Arthur once represented comfort, and the promise of a life “which didn’t require me to make decisions anymore”.

Hera makes Arthur sound like a pet rock she has tried to use to orient herself. Gray makes him sound like a cliché. An English man who manages to combine “a high-powered job with the nervous shyness of someone who was bullied in high school”, he resembles an early-career Hugh Grant, bumbling around in cargo pants and “chemist-bought sunglasses”.

But for all his awkward British sensitivity, he avoids the subject of his marriage like the plague, which renders him spineless.

The plot is littered with oversights that raise questions about the editing process. For example, when Hera moves to a strangely unidentified city in the UK, seemingly on a kind of vengeful whim, the entire episode is treated with remarkable gloss.

In a country where work and accommodation are notoriously hard to acquire, Hera finds both with miraculous speed, and once there, does nothing except sleep with lots of terrible people and moon over Arthur. This, together with Gray’s painfully inaccurate stereotyping of British culture, including “trash” British coffee, pretentious British art students and small-minded British pub-goers, continues for 50 pages, while Hera’s emotional arc remains stagnant.

When COVID hits, lockdown and isolation ensue, and again, Hera traverses these with ease. Weirdly, she makes no friends in the UK and her flatmate, Poppy, barely a whisper on the page, inexplicably comes and goes sporadically despite government restrictions. Despite being entirely alone overseas during the outbreak of a deadly virus, Hera continues to be preoccupied with nothing more than missing Arthur.

Another example occurs when Hera and Arthur find themselves in Hera’s estranged mother’s neighbourhood. By coincidence that feels contrived, Hera spies her mother outside a restaurant. But Gray skims past this detail, opening and shutting down a valuable plot opportunity within two paragraphs, making you wonder why it was included in the first place.

Gray’s writing is intelligent and effervescent, and this is an entertaining debut. But at almost 400 pages, given the one-trick plot and skinny characterisation, it’s far too long: which seems to be another editing issue.

Hera is amusing, but far too preoccupied with herself to be in touch with her vulnerability. She asks questions of herself that she doesn’t bother to answer. She is self-aware but unable to think analytically. And while her flaws are central to her character, like too many Sad Bad Girls, she is self-consciously self-abasing almost for the sake of it.

Read more: My Year of Rest and Relaxation: 'sad-girl' fetishism or 'cuttingly funny' feminist satire?

Insightful exploration of a traumatised woman

By contrast, Lucy Treloar’s new novel, Days of Innocence and Wonder, explores the search for meaning and connection with depth and sensitivity, from the perspective of trauma.

This is the author’s third book and her first foray into contemporary fiction. It refreshingly defies familiar genre categories, being neither a straightforward thriller nor crime. Needless to say, this is not the story of a Sad Bad Girl, but an insightful and sensitive exploration of a traumatised woman.

Protagonist Till is a 23-year-old woman on the run from a devastating childhood experience that continues to bleed into the present. Angry, haunted and scared, she’s not so much flawed as scarred. Disrupting ideas about safety and refuge, unsettling the boundaries of space and time, this is a story about how the past shapes the present. Ultimately, Till must learn what this means for her and what she can do about it – or not.

Written in response to the ongoing problem of male violence and misogygny that propelled the 2021 women’s March4Justice movement across Australia, the novel poses questions about reckoning and the loss of innocence. Occasionally led by an unidentified first-person perspective that breaks through the narrative with leading questions, it also raises the issue of shattered identity. The final page responds to this in heartbreaking fashion.

At the start of the novel, Till is newly terrified and flees her parents’ home in Melbourne, driving with no destination in mind, finally stopping at the fictional ghost town of Wirowie in South Australia. Here, she sets up camp in the old, crumbling railway station and, despite her wounded, defensive, suspicious disposition, slowly begins to find a sense of community among the scattered inhabitants.

But the deserted township, with its dusty streets and abandoned buildings, harbours dangers of its own, forcing her to choose between running again, or claiming her precarious ground and facing down the threat.

Elegantly written, the novel possesses a dreamlike quality reminiscent of Kate Hamer’s mystery novels,though at times the evocative atmosphere can feel disorientating. Perhaps this is a conscious decision, designed to pitch the reader into Till’s fractured psyche – where hazy memories blur the line between dreams and fleeting impressions of the past.

Certainly, in its depiction of psychological trauma, and the ways children adapt in order to survive terrifying experiences, the narrative is astute and considered.

Addresses structural misogyny

There are inconsistencies. For example, I found it wholly unfeasible that the guarded and mistrustful Till would invite shopkeeper Ken into her home within minutes of meeting him. And without providing spoilers, the way Till’s past continues to track her is hard to believe and not adequately explored or explained.

While this preserves a mysterious quality, it leaves too many important questions unanswered, and too many loose threads hanging. Just a few more well-placed beats would have made all the difference.

Overall though, this is a moving novel that addresses the structural misogyny in Australian society, as well as the ways it intersects with the persistent issue of racism. It constitutes a quietly powerful response to these things in the form of a psychological suspense novel that refuses the heightened drama of conventional thriller territory.

Though set in a dilapidated rural area around a tiny community impacted by tragedy, the story avoids the trappings of outback crime and heroic metropolitan detectives.

Instead, like Emily Maguire’s An Isolated Incident (which was shortlisted for both the Miles Franklin and the Stella Prize) Treloar’s novel foregrounds the female experience of violence and trauma considerately and thoughtfully. It confronts the legacy of male brutality without sidestepping the horrors or overdramatising them.

A slow-burning tale about the power of female self-agency, Days of Innocence and Wonder carries a quiet sense of hope and the promise of a protagonist who is finally able to grow up. And that, in itself, sets Till apart from the Sad Bad Girls.

Liz Evans does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.