Everything can be traced back to Les Paul. First, consider that he invented the solid-body electric guitar. The Gibson model that has carried his name since the 1950s is one of the most iconic instruments in rock and has been favoured by guitar greats including Jimmy Page, Pete Townshend, Mick Ronson, Slash, Paul Kossoff… the list goes on.

A virtuoso player himself, Paul helped push the boundaries of the guitar with flash and finesse. In his hands it became a powerful new instrument, essentially taking it from a horse-drawn buggy to a sports car.

On a much larger scale, the whole idea of an album in the modern sense, as a studio production rather than a captured live performance, begins with Les Paul. He invented multi-track recording (along with effects units including reverb, echo and delay), the home studio and the very notion of the artist as a producer.

It’s not a stretch to call Les Paul the Thomas Edison of rock. Or as Slash put it: “Les was a total fuckin’ maverick.”

Paul was also a generous, personable guy who wore his legend lightly. Right up until his passing at the age of 94 in 2009 he was teaching seminars, gigging regularly, trading quips and licks with musician friends such as Keith Richards and Eddie Van Halen, and working on new inventions in his workshop at home in New Jersey. I was fortunate enough to spend a few hours with him on two occasions, and found him to be, for all his accomplishments, remarkably modest.

That modesty probably had to do with his Midwestern upbringing. Born Lester Polsfuss on June 9, 1915 in Waukesha, Wisconsin, he strummed his first guitar when he was eight. Shortly after, he dismantled that guitar.

“From the second I got my first guitar, I noticed things that could be improved upon,” he told me. “I corrected the obstacles and made it easier to play. While other kids were out ice-skating or playing ball, I was inside, trying to learn about how sound waves travel. I recognised I had a gift, but never did I get where I felt like I was better than anybody. I was just the kid who was always taking things apart.”

Soaking up the jazz, pop and country sound waves from the family radio, he soon became an adolescent one-man band. Performing under the name Rhubarb Red, he sang, blew harmonica, beat a washtub and played guitar at a local barbecue stand. By now he’d graduated from his Sears & Roebuck acoustic to a more professional Gibson L-5 hollow body.

He said: “One night I was playing, someone said: ‘Your voice is fine, your harmonica is fine, but your guitar’s not loud enough.’ I went home determined to find an answer. “First, I took a bit of steel railroad track and strung a string along it,” he continued. “Underneath I put the receiver part of the telephone. I hooked it up to the radio, and it worked.

"I went running to my mother and said: ‘I found it! She said: ‘That’ll be the day you see a cowboy on a horse playing a piece of railroad track!’ So that idea went right out the window. Next I tried a four-by-four plank of wood with a string stretched on it. That was the very first time I ever made a solid body guitar. Everything in the years after was refining that idea, or making a better block of wood with a string on it."

With his mother’s blessing, Les dropped out of high school to pursue music. By then he was performing on the radio on weekends in St. Louis. A year later he moved to Chicago and made his first professional recordings, dropping Rhubarb Red and shortening his birth name to Les Paul. Moving on to New York, he and his trio won an audition on Fred Waring’s popular radio programme. Suddenly, Les was reaching an audience of millions nationwide.

“It was the biggest break of my life, and a great education,” he said. As Les Paul’s profile rose, he continued to pursue the idea of a guitar that could “sustain for days”. Coincidentally, just a few blocks from his apartment was a new showroom and laboratory belonging to the Epiphone guitar company.

Paul introduced himself, and before long “it was no problem to get permission to use their machinery and equipment on Sundays, when the place was shut down”. As he’d done with other things as a boy, he took the Epiphone guitars apart, making notes about their construction, all in pursuit of his solid-body dream. He nicknamed his prototype guitar The Log, because, well, it looked like a straight piece of timber with strings, frets and pickups.

Paul recalled the first time he played it in front of an audience: “I took it to a tavern in Queens, and people didn’t even notice. There I was, flying up and down the neck… No response. So I took it back to the shop, added ‘wings’, fastening two sides on the log so that it looked like a guitar. The next week, the audience applauded. I realised then that most people hear with their eyes!”

From Waring’s show, Paul moved on to accompanying America’s biggest star, singer Bing Crosby. On their first hit together, the wartime ballad It’s Been A Long, Long Time, Paul played one of his most lyrical solos ever. It didn’t have any of the speedy pyrotechnics that he’d become famous for, but it remained one of his favourites.

“There was a case of you don’t have to play a lot of notes, you just have to play the right notes,” he said. “And that tells the whole story.” In 1946, while looking for a singer to front his own trio, Paul met a pretty young guitarist-vocalist called Colleen Summers. “She had the smoothest, sweetest voice I’d ever heard,” he said. The two quickly became partners in music and in love, and Summers changed her name to Mary Ford.

But in 1948, just as the duo started to gather steam, playing gigs and doing their first recordings, tragedy struck. On an icy winter road in Oklahoma they were in a car accident that left Paul’s right arm shattered in several places. He was in hospital for more than a year. The prognosis was that he’d never play guitar again. Rather than have the arm amputated, he convinced doctors to set the bone at such an angle that he could still strum and pick.

Decades later, he said: “That was an asset to be disabled that badly. You know, in the 1940s I felt as though I played the best I’ll ever play. I had a lot of dexterity and technique. If I thought of it, I could play it. But the accident forced me to stop doing everything I knew, and think about this concept for a whole new kind of music.” When Paul recovered, he began chasing that concept, experimenting with “sound-on-sound” recording in his garage studio.

“Bing Crosby gave me a brand new Ampex tape recorder in 1949,” he said, “and I immediately started thinking about how to modify it. With the multi-tracking, at first I didn’t tell anybody what I was doing. I just locked myself out there in that garage and said: ‘I’m going to make a sound where people will be able to tell me from anybody else.’ And it had to be different. Something that was brand new.”

He recalled the night he did his first successful multi-tracking experiment: “I’d asked Ampex for a fourth head for the recorder, and they just drilled a hole and put it in there. They had no idea what I was doing, and I didn’t tell them until five years later. As a test, we recorded Mary’s voice, then my guitar. Then we added harmonies. They were all there on the tape. I said: ‘By God, it works!’ Mary and I were dancing around the room. We were the two happiest people in the world.”

The Les Paul & Mary Ford sound was an elaborate layer cake. It featured Mary’s warm, effortless vocal harmonies at its centre, with Paul’s multi-tracked guitars zooming around, providing percolating beds and exquisitely arranged counterpoints. It sounded folksy and futuristic, smooth and strange. And it was all recorded at home, an unthinkable feat at the time.

Record buyers may not have understood what they were hearing, but they loved it. In the duo’s 10 years together they had more than 40 Top-40 hits, including classics such as How High The Moon, Smoke Rings, Vaya Con Dios and Bye Bye Love. And from their big bang, everything in recorded popular music followed.

More specifically, you can draw lines to many future points in rock, including the one-man vocal choruses of ELO and Todd Rundgren, the elaborate guitar orchestrations of Brian May and Lindsey Buckingham, the flashy leads of Jimmy Page and Eddie Van Halen.

Jeff Beck said: “I remember hearing How High The Moon as a kid. The sound was fantastic, especially the slap-echo and the trebly guitar. I had never heard an instrument like that before. It just leapt out of the speakers. It still sounds fresh today.”

Paul McCartney recalled that during The Beatles’ early days in Liverpool they kicked off every performance with that song. “That would get the crowd’s attention right away,” he said. “Everybody was trying to be a Les Paul clone in those days.”

As he and Mary became international stars, Les finally had the clout to realise his dream of perfecting a solid-body guitar. A few years previously, the Gibson company had dismissed Les’s prototype as “a broomstick with pickups”.

Now, with competitor Fender Guitars successfully launching a line of solid bodies, Paul said, “Gibson woke up and went, ‘Find me that character with the broomstick!’”

He recalled the meeting that led to his namesake guitar: “We all faced the fact that the dense wood would be too heavy, and we had to lighten it up. As for the shape, I had presented this flat-surfaced guitar to the chairman of the board at Gibson. He said: ‘Do you like violins?’ I said: ‘I love them.’

We went back to his vault and looked at the Stradivariuses. He said: ‘We could make a beautiful guitar with these kind of contours.’ And right there we decided to make the shape of the guitar like we did. The next thing that came along was how beautiful you could make it and what a great friend it could be. It turned out to be beyond anybody’s dream.”

The first Les Paul guitars debuted in summer 1952, with Les and Mary giving them a concert debut at the Paramount in New York. (For the stage, Les devised a black box called the Les Paulveriser that replicated his multi-tracked sound on records, an invention anticipating ‘looper’ pedals by decades).

The Gibson Les Paul’s solid body, and other design innovations like humbucking pickups and a tune-o-matic bridge, soon made it the favoured instrument of the new generation of rock’n’rollers. “The sustain, the ache and roar and ferocity and subtleness is just limitless,” Bonnie Raitt said of the Gibson Les Paul guitar.

Les and Mary’s chart run continued until they split in 1964. “We never stopped loving each other,” he said. “After the divorce was settled and the pressure was off, we became very close again.”

Mary remarried, stayed in California, and did occasional performances. She struggled with diabetes and alcoholism until her death in 1977. During the 60s, Paul went into semi-retirement, working as an A&R man for Columbia Records. He also began suffering from both arthritis and hearing loss.

Rather than despair, he re-taught himself to fret the guitar with two fingers rather than four – similar to the style of Django Reinhardt – and designed a custom hearing aid. In 1978 his old friend and guitar great Chet Atkins lured him out of retirement, and the pair recorded two acclaimed duet albums in Nashville: Chester And Lester and Guitar Monsters.

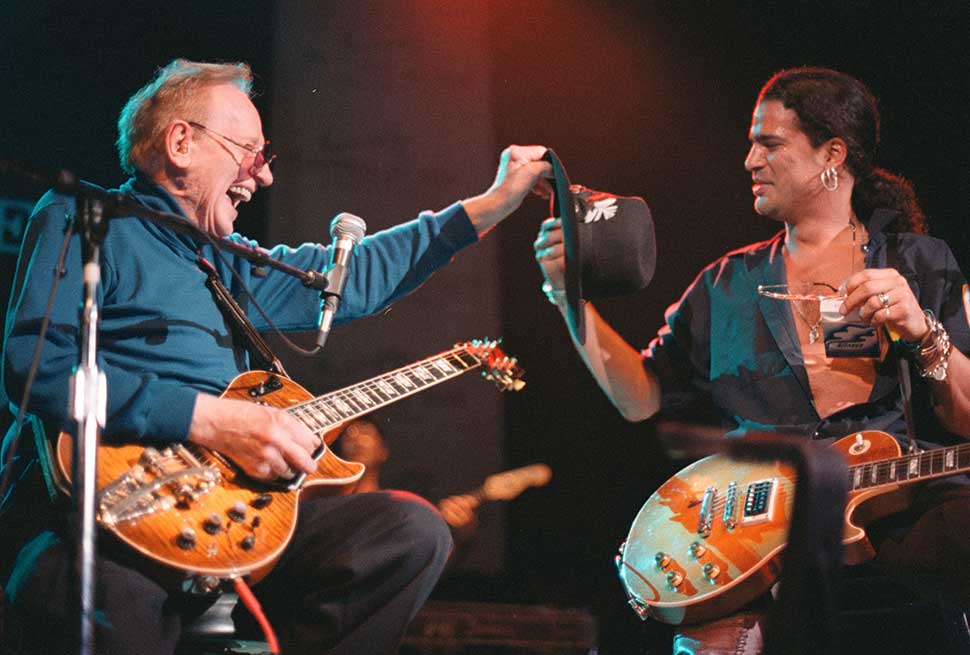

During the last three decades of his life, Paul held court with Monday-night residencies at two New York City clubs, Fat Tuesday’s and Iridium. The list of musical friends who sat in on these nights was like a Who’s Who of rock, including Paul McCartney, Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, Keith Richards, Brian May, Steve Howe, Peter Frampton, Steve Miller, Billy Gibbons, Mark Knopfler, Richie Sambora and Slash.

“It’s been a chance to stay active and make new friends,” Paul said. “Also, it makes me continue to learn. It’s great therapy for a ninety-year-old fella like myself. Much better than taking a pill!”

Appropriately, and maybe uniquely, Paul was inducted into both the Rock And Roll Hall of Fame and the Inventors Hall Of Fame, keeping company in the former with Chuck Berry and the latter with Nikola Tesla.

“Kids nowadays don’t even really know that kind of history,” Slash said. “But it’s important to have an understanding of that delay pedal that you’re using and where the original concept came from. Whenever you hear guitar harmonies recorded, like Brian May used to record harmonies on all of Queen’s records, that was all Les Paul stuff. He invented the technique where you could layer guitars. Before that, people just had to play live and that was it.”

“It’s hard to tell how many people he put on the path,” said Steve Miller, who was Les’s godson. “He was my musical guide and my main inspiration. And the most generous man ever. Just a wonderful, wonderful spirit.”

Les Paul was also the first famous musician to make it to 90 and still be active. His attitude on ageing remains an inspiration.

“You can’t be a sissy,” he told me. “It may not dawn on you until you’re in your sixties that you’re on the ass-end of the boat, but you have to face the fact. For me, I’m pushing a hundred. Every tick of the clock means something. There are times when I’ve got to sweep the fact under the rug, but the rug is pretty crowded. The way to handle it is to keep your mind occupied.

"Love your work. Otherwise you’re sitting around and drying up. I’m a person who says I can’t wait to get out of bed because I’ve got so much to do. Every hour that I’ve got, I’m busy. I look forward to tomorrow, no matter what.”