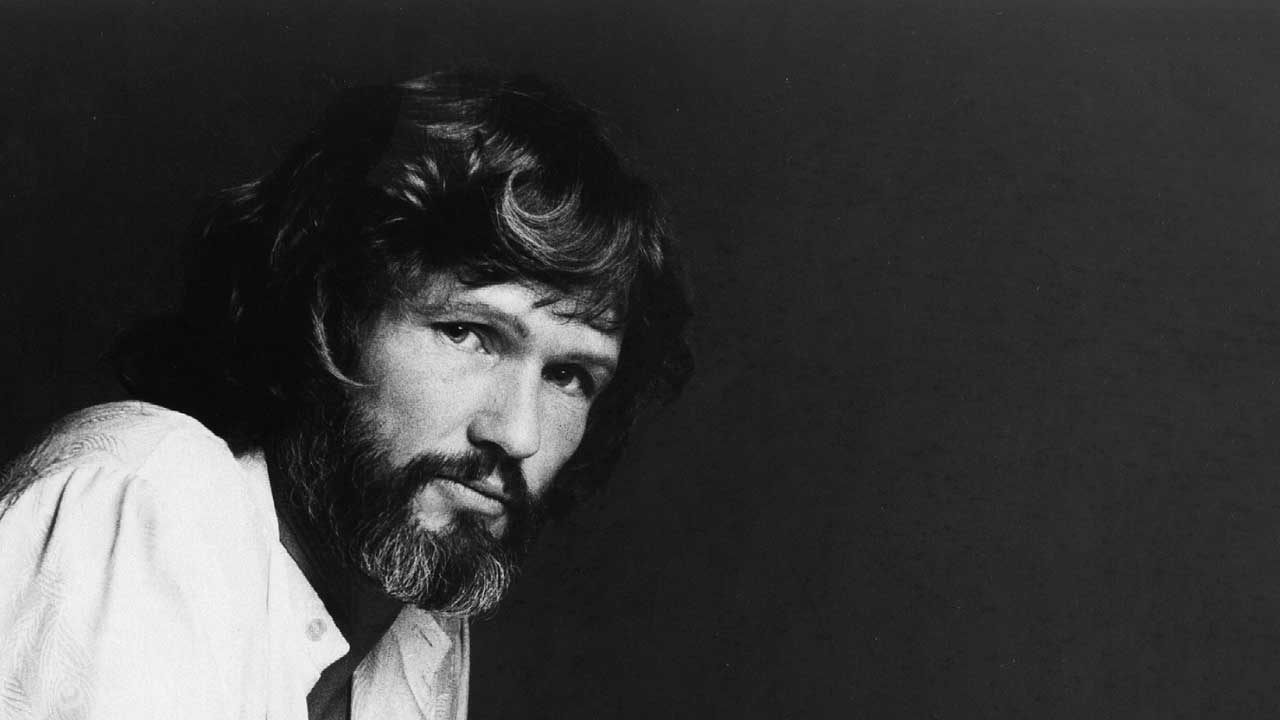

In 2006, the late Kris Kristofferson released an acclaimed new album, This Old Road, and spoke to writer Paul Sexton frankly about his life as an actor, country singer and songwriter.

The South By Southwest music festival of 2006 was, as ever, the playground of the rock buzz bands and artists of the day, from Arctic Monkeys to Corinne Bailey Rae. But its vast line-up of 1,400 acts also welcomed more than a few roots, country and Americana notables. Among them was a man about to celebrate his 70th birthday with an excellent new album, This Old Road, which only added to the almost mythological allure of Kris Kristofferson.

Short of hanging out with him in Nashville, in the bars of Broadway, there was something appropriate about meeting this outspoken frontiersman in the improbably liberal bolthole of Austin, Texas. Kristofferson grew up in the south of the state, which has since become one of the most Republican in the Union. He’s spent a lifetime using his charisma on record, stage and the big screen to challenge perceptions of himself, of America and of the whole world around him.

As he proved again on the Feeling Mortal album, released on his own label at the beginning of 2013, and on which he confronts his advancing age with fearless guile, he’s still doing it. Seven years ago, articulate, engaged and effortlessly cool, he would prove to be mesmerising company.

Kris Kristofferson beamed as he drew the direct connection between his largely unplugged, deliberately unembellished This Old Road album and the spirit that existed when the Texan first hit Tennessee back in the mid-1960s.

“It’s really going back to the way it was when I went to Nashville and wanted to be a serious songwriter,” he said. “The guys I hung out with, who also hadn’t made it yet, they were a respected clique of underground guys. They didn’t want to hear any good musicianship or vocalising, they didn’t care if you sounded like George Jones or Ray Charles. They wanted to hear the song, and what it meant.

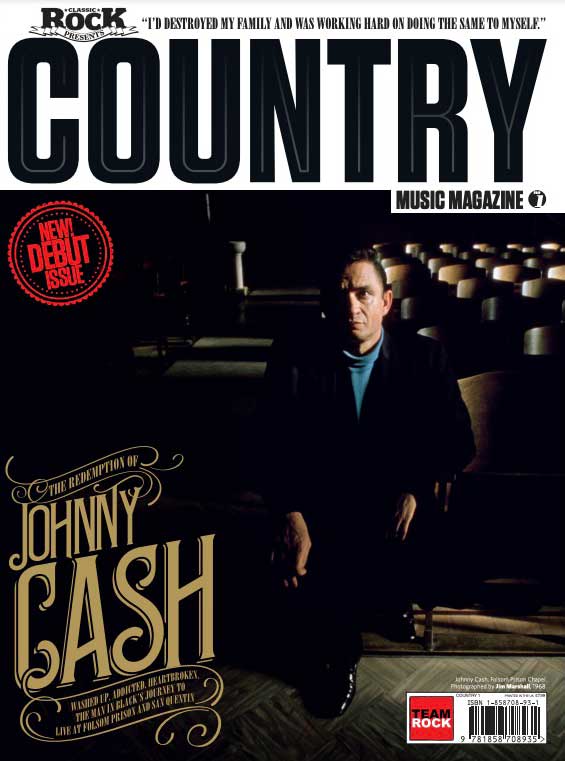

“It hasn’t been since maybe the second album, The Silver Tongued Devil And I, that I’ve had such a positive response. I think it might be in some part because of the ground that Johnny Cash broke with his stark stuff that he did with Rick Rubin. I really don’t know, but it’s gratifying at this end of the road.”

As we’ll see, Cash’s name would crop up often in our conversation. But ahead of that, we dug deep into Kristofferson’s early history, remembering the lesser-reported days of his mid-20s, chasing chart success on this side of the Atlantic.

After studying creative writing at college in California, Kris won a Rhodes scholarship to Oxford in 1958, and as a Texan reading Blake amid the dreaming spires, a pop career suddenly beckoned.

“I hadn’t paid any dues as a musician,” he said. “I had made a record with a friend of mine who used to play with me in college. A guy that worked in a music store took us in the back and recorded us. “Then when I got to Oxford, I remember that I read an ad in the paper that said ‘Just dial F-A-M-E’, and that was [placed by] Paul Lincoln, who had the Two I’s, the club where Tommy Steele and a bunch of other people got started. I went in there, and I guess he reckoned I’d be marketable as this ‘Yank at Oxford’. I had a bunch of songs. Looking back on them, they weren’t that good, but good enough that he got me a session with Top Rank Records.

“There were articles in the paper because I was boxing against Cambridge at the same time, and [rising English songwriter-producer] Tony Hatch, I think the first session he produced was mine. Then this guy that I’d recorded for, back in the States, heard about it and he threatened to sue.

“They didn’t figure I was worth getting sued over, I guess, so the record never came out, which was fortunate for me,” he chuckled, “because they’d already changed my name to Kris Carson. I think God protects fools and songwriters, and he was looking after me there, when I didn’t know what the hell I was doing.

“I remember Paul Lincoln said, ‘Kristofferson, that’s too many syllables. Sinatra was three and you can’t go any higher than that.’ I saw him afterwards. I went by some pub he owned, after I’d made it, and we laughed about how far I’d come. He probably thought I still couldn’t sing worth a damn."

He returned to the States, and his real name. “When they didn’t put that thing out, I kind of gave up the music idea,” he said. “I was already in the army; my active duty was just deferred during the Oxford time. I went through jump school, flight school and ranger school, and did a three-year tour in Germany.

“While I was there, I started doing music again and had a little band that would play in the clubs. My platoon leader had a relative in Nashville, a songwriter and publisher, and he sent her some of my stuff. She responded that if I was in the area, to come by. It was all the invitation I needed.”

He became a night-time janitor at Columbia Records’ studios in Nashville, meeting Cash for the first time, as well as George Jones and even Bob Dylan circa Blonde On Blonde. There was some early songwriting success, though, when his Viet Nam Blues went to No.12 on the country chart in 1966 for Dave Dudley, the prolific Wisconsin hitmaker of many a truck-driving song, best known for his 1970 country bestseller The Pool Shark.

“When I went to Nashville, people still called it ‘shit-kicking music’,” he told me. “I fell in love with the whole life; it was so different from the military or the academic world. It was people really creating stuff and knocking each other out every night, and staying up for a week at a time. They called it ‘roaring’ back in those days.”

He became a little too good at roaring. In addition to his night shift at Columbia, and while he wasn’t passing tapes of his songs to Cash or anyone else he could get close to, Kristofferson had a day job at Nashville’s Tally Ho Tavern. Years later, his fellow Highwayman Waylon Jennings would describe it as “like putting a fox in charge of a chicken coop”.

Kristofferson was signed as an artist by Epic in 1967, but although he was already 31, and despite going on to be championed by Cash and others, he would still be better known as a songwriter for the remainder of the decade.

In 1968 and ’69, his songs sold in versions by such artists as Roy Drusky, Billy Walker and Faron Young, who went Top 5 with his Your Time’s Comin’, and before the end of the decade, Roger Miller became the first star to chart with a version of Me And Bobby McGee, written by Kris with Fred Foster.

It was tough, but these were times Kristofferson remembered fondly in our meeting. It seemed, I told him, as though the competition in Nashville was a little more healthy back then.

“It was,” he said, “because the old guys hung out with the serious new guys – they weren’t standoffish at all. Guys like Harlan Howard would be encouraging, and Faron Young and Cowboy Jack Clement, they would all would listen to you.

“It wasn’t as competitive. There were a lot of good songwriters like Tom T. Hall and Harlan, but it was more about delighting in each other’s work. It was as nice to hear another good songwriter, almost, as it was to write your own. And they really weren’t into being dazzled by your footwork at all. They didn’t care if you could play the guitar real good, or sing good. They wanted to hear what the song was about, and that was good training.”

The trickle of covers would tide him over. “Even that trickle was better than the four years before it,” he remembered. “I felt I was making it then.”

1970 brought his first album for Monument, a self-titled set that sold slowly at first but truly established a song catalogue that was ever more in demand. Small wonder, when you remember that it included Me And Bobby McGee, Help Me Make It Through The Night, For The Good Times and Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down.

“Bobby McGee, I never wrote that for a girl to sing,” he revealed. “But Janis [Joplin], I can’t do it without thinking of her. It was all happening so fast back then. I was just amazed, from one [cover] to the other. Help Me Make It Through The Night, Jerry Lee Lewis cut it too and it was great, and Willie [Nelson] cut a great version.”

But when he got hot as a songwriter, the temperature really soared. Almost unbelievably, of the five songs nominated as Best Country Song at the Grammy Awards of 1972, Kristofferson wrote three of them, winning for Sammi Smith’s version of Help Me Make It Through The Night and being shortlisted for Bobby Bare’s version of McGee and Ray Price’s recording of For The Good Times.

Could there be one overriding favourite among the hundreds of interpretations from his songbook?

“No, there’s different ones, but it’s kind of like your kids, different ones meant something special,” said the father of eight. “Like Johnny Cash, when he made Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down into the record of the year, and Janis, unfortunately that was after she died, but I guess it was the biggest single record she had.

“I still admire the same people – Ray Charles, Hank Williams, Merle Haggard, Willie Nelson, Bob Dylan. I think Bob probably had as much to do with me going the direction I did as anyone. He certainly had a big effect on making people respect country music, because he had such respect for Johnny Cash, and he recorded in Nashville.”

In a fearlessly real approach that has few equals in all of country, and not too many beyond it, Kristofferson has never sidestepped difficult issues. Even at his commercial peak, his unflinching pen addressed taboos even as it created hits, confronting alcohol and drug dependency on Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down’, spiritual insecurity on Why Me and physical desire on Help Me Make It Through The Night in a way that female interpreters were also comfortable with, from Sammi Smith to Gladys Knight.

“Ever since I committed myself to this way of making a living, I thought it was my responsibility to tell the truth as I see it,” he declared. “Sometimes that made me unmarketable, particularly in country music. But I guess if you hang around long enough, they probably figure you’re entitled to say whatever you believe, and fortunately that’s what I’ve always been trying to do.”

By the time his own music career cooled, Kristofferson was a substantial motion picture star. “I never had an idea,” he said, “that in a matter of years, I’d be doing a film with Barbra Streisand [A Star Is Born] and my whole band would be in it too, and films with Marty Scorsese and Sam Peckinpah, and people I just admired from afar. It was a pretty good ride, for a long time.”

A wild one, too, complete with the rock’n’roll marriage to his sometime recording partner, Rita Coolidge, and another intimate relationship, with the bottle. Nashville writer Peter Cooper once said that Kristofferson had lived enough to play the parts of sinner, sage, fool, drunkard, hard-ass, villain and martyr from memory.

“I think I medicated myself with a lot of whisky because I’m still nervous going on stage,” he said, “as if I was going into a boxing match, until the first punch in the face.”

But the movies chose him, rather than the other way around. “My film work was getting a lot more attention. Unfortunately, the record company I was with was slowly sinking in the west, so my music wasn’t getting a bunch of attention, so people thought of me as a movie actor, especially after A Star Is Born. The truth is that for about 30 years there, I was either making a film or I was on the road with my band.

“For a long time, the films were supporting the music, but now the music is supporting the family, and the films are fewer and further between. Now, some of the audiences are so young, they just know me from the Blade movies.

“I felt I was really lucky to be doing both things, because from the time I started performing on the stage, I was doing films. The first club I worked was the Troubadour, and there were all these film people there. I remember Harry Dean Stanton brought me a script the first week we were there. I don’t think I really thought about it. Looking back now, it was a real roller-coaster ride, but at the time we were just enjoying it.”

Even by 2006, Johnny was gone, and Waylon was gone. Did Kristofferson ever think of himself as continuing some sort of outlaw line?

“Not really. I never really compare myself to John – to me there’s nobody like him,” he said. “I feel like I’m still true to the same things I admired back then – Willie, Merle Haggard, the guys who were serious about the music.

“I think there probably are other guys who can’t do it any other way, like I hope John Prine will always be respected. He was writing like an old man when he was a kid. And I feel there is a desire to hear that stuff now, because we’re all still working. Willie’s working every day.”

He had hope for the future of country, expressing approval of the likes of Gretchen Wilson and Keith Urban.

“I like a lot of those guys, but I’m so out of the loop that mostly I listen to the guys I listened to before. I’m still listening to Bob Dylan, because he’s still writing new stuff, and Merle, and Willie.

“Once, you were accepted, like Ernest Tubb or Roy Acuff, and you were allowed to go on forever. The first time I noticed that had changed was when Columbia got rid of Johnny Cash. But the response to John since he died, he’s sold more records now than he did alive – you see him everywhere.”

From the continuing political engagement of his lyrics on This Old Road, I thought that Kristofferson was unlikely to admit he had mellowed over the years. He laughed.

“No, Jeez… well, I think in some ways I might have mellowed, because you can’t go around getting in fights all the time. The older you get, you’ll get a little punished.

“But no, I had always heard that as you got older you got more conservative, and I certainly haven’t. I think I’ll probably still be outspoken till they throw dirt on me."

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock Presents Country (Issue 1, September 2013). Kris Kristofferson died on September 28, 2024.