Lately, Ian McEwan has found himself reading a lot of Ian McEwan. It’s not that the 74-year-old author has been struck by a sudden attack of solipsism; rather, he’s deep in preparation for a one-off performance with the BBC Symphony Orchestra at the Barbican. Backed by 80 musicians, the Booker Prize winner will deliver extracts from a career that stretches over 16 novels, from the psychological horror of 1978 debut The Concrete Garden to bestselling tragic romances such as Atonement and On Chesil Beach. Most recently, he published Lessons, a sprawling, semi-autobiographical look back at the sweep of history in his lifetime. Selecting which passages to perform from that rich material has been a revealing process. “It was like a review of a big chunk of my adult life,” says McEwan. “There were moments when my fingers twitched around an imaginary blue pencil and I thought: ‘I wouldn’t punctuate that like that now.’ Other times I was thinking: ‘Wow, that was good. Have I declined?’ It was a fascinating thing to do.”

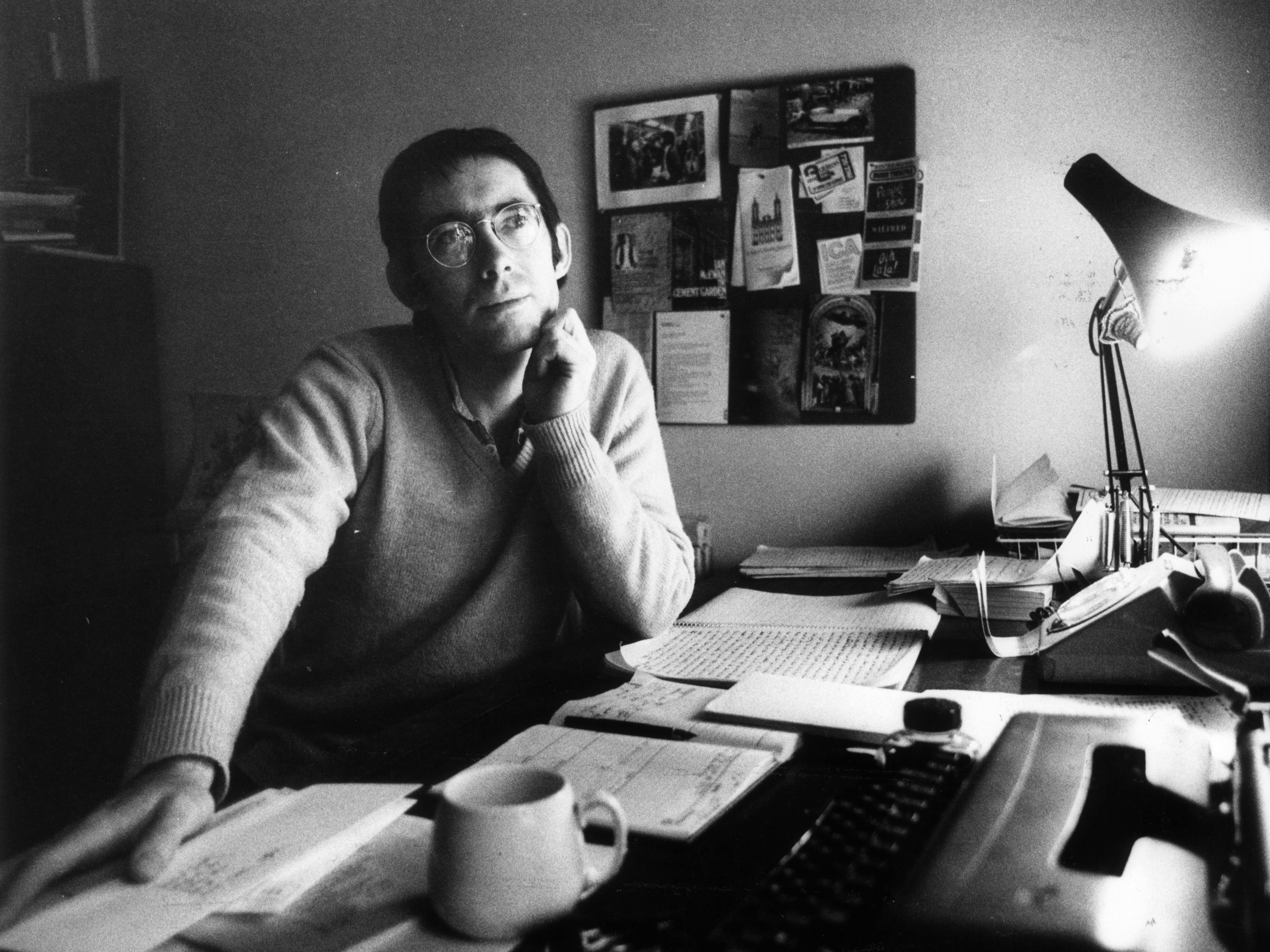

McEwan is talking to me from his Cotswolds home. Surrounded by books, he’s engaging and erudite; a deep thinker with a professorial manner. He also has a knack for swerving questions – indeed, ask him about JK Rowling, in support of whom he signed an open letter in 2020 after she received “hate speech” for her views on transgender issues, and he’ll bat you away, deftly steering the conversation back to, say, the troubling rise of AI. Certainly, he’s interested in talking about the way the internet has warped social discourse since he first arrived on the literary scene in the late Seventies. Back then, his dark, cerebral work quickly earned him the nickname “Ian Macabre”; the restrained realism of his prose style only made the perversities captured in his tales all the more shocking.

He got an early taste of notoriety in 1979 when the BBC abandoned a television version of his short story “Solid Geometry” over concerns about the Victorian antique at the heart of the narrative: a foot-long pickled penis. Yet while the editor’s pencil may have hovered in McEwan’s mind’s eye when it came to matters of punctuation, he has no qualms about his work’s subversive and often provocative content. He’s definitely never been tempted to seek the counsel of sensitivity readers of the sort who’ve recently overseen controversial edits to the work of Roald Dahl and Ian Fleming. “I don’t know whether I’m just lucky, but no sensitivity readers have entered my life, or even my private life,” says McEwan. “I keep reading about it, but I seem to have escaped that particular whipping.”

Although some of his peers have decried posthumous revisions to authors’ works, with Salman Rushdie calling them “absurd censorship”, McEwan argues there are more important things to get worked up about. “Life’s too short,” he says. “What boils my blood is the Russian invasion of Ukraine. One has to be highly selective on one’s blood boiling.”

McEwan has long been a keen observer of European geopolitics. At the Barbican he’ll read from a chapter in Lessons in which his protagonist, Roland Baines, travels to Berlin for the momentous day in 1989 when the wall came down. It’s an experience drawn directly from McEwan’s own life, including the British TV crew who mistook the author for an East Berliner crossing the divide for the first time. That exuberant moment of hope 34 years ago seems very far away today. “I chart my own political optimism-pessimism scale from ’89 through the Nineties, and then it begins to fall apart in this century,” says McEwan. “As I write in Lessons, there’s a distinction to be made with political moments between whether they’re gateways or peaks. I thought ’89 was a gateway to a whole new future, as did many of us, but it turned out just to be a peak. So yes, I feel rather depressed about the way things are, and have been for a while.”

McEwan finds little inspiring in politics closer to home. He has been a vocal critic of Brexit, publishing the satirical novella The Cockroach on the subject in 2019. While he unenthusiastically suggests that the coronation of King Charles in May could lift the public mood (“These things do. It’ll be fine”), he says he was not inclined to read Prince Harry’s recent memoir. “I’ve got to keep a lot of neurons spare and ready for other use,” he demurs. “I read some coverage. I got the idea.”

On the day we speak, the headlines are dominated by Gary Lineker’s suspension from Match of the Day after he criticised government immigration policy on social media. McEwan chuckles about the former footballer’s new-found place as a leader of the opposition. “Do you remember there was a survey asking, if Britain was a republic, who should be president?” he asks. “It was overwhelmingly Lineker! Well now, there he is! He’s walking on air, an angel for the centre left!”

McEwan rather likes the idea of a British republic, and says he was impressed by Irish president Mary Robinson in the Nineties. “I thought: ‘Why not?’ She’s a highly articulate trained barrister who can get her mind around constitutional matters,” he remembers. “One problem with the monarchy is that it more or less has to do what the government of the day says it must do, because it’s not elected. So the Queen signed, for example, to give her permission for the proroguing of parliament [ahead of Brexit in 2019]. I don’t think Mary Robinson would have done that. Should the government of the day have the power to suspend parliament at will? Probably not! I think she might have sent them packing.”

While his forthcoming Barbican performance will mark McEwan’s first appearance on stage with an orchestra, classical music has been a running theme throughout his life and work. Born in Aldershot in 1948, he spent his childhood wherever his army major father was posted, bouncing between countries such as Singapore, Germany and Libya. It was at 16, while at school in Suffolk, that he received a birthday present that would change his life: a reel-to-reel tape recorder. “I started a self-education,” he remembers. “I was so passionate about music generally. I recorded a lot of jazz, a lot of rock’n’roll, a lot of early Dylan. It was all available as I was at a very musical school, and it was great discovering things for myself.”

Music and musicians have featured in his work ever since, from the distraught mother in 1987’s The Child in Time, who spends hours each day practising Bach, to the celebrated British composer character he created for Amsterdam, which won him the Booker Prize in 1998. The Tallis family in 2001’s Atonement share a name with the 16th-century English composer Thomas Tallis, and he illustrated the mutual incomprehension between the newlyweds in 2007’s On Chesil Beach by making one a Mozart aficionado and the other a rock’n’roll fan. “When she listens to Chuck Berry, which he plays her very loudly, she says: ‘Well it sounds very sweet,’ and he knows she’s completely missed the point!” he says. “Music is part of my mental furniture, who I am and what I am.”

McEwan graduated from the University of Sussex with a degree in English literature in 1970. His breakthrough came just a couple of years later when the New American Review published “Homemade”, his short story about teenage incest. “Probably the biggest thrill of my life was being sent a copy,” recalls McEwan. “On the cover it said, all in equal typeface size: ‘Philip Roth, Günter Grass, Ian McEwan, Susan Sontag.’ I just thought: ‘Wow!’”

How old is Rupert Murdoch? These guys don’t die. I think there’s a rejuvenating hormone in power that keeps these guys out of the grave— Ian McEwan

This early success catapulted him into a burgeoning literary scene alongside the likes of Martin Amis, Julian Barnes and Christopher Hitchens. “We all met when we were about to publish our first books,” remembers McEwan. “We didn’t think about the future particularly. One doesn’t, in one’s twenties. It was enough to be publishing a book.”

That thrill has not yet left him. After the Barbican show, McEwan will return to the Cotswolds to get back to work on his next novel. “It’s too soon to speak about it now, I don’t want to blow it away,” he says cagily. “A lot of it’s not in words yet. It’s just a lot of hunches.” Like many of us, he’s also eagerly awaiting the imminent final season of Succession. “I’m backing Brian Cox [who plays octogenarian media baron Logan Roy], I think he’s going to go on,” he says with a smile. “I mean, how old is Murdoch? These guys don’t die. I think there’s a rejuvenating hormone in power that keeps these guys out of the grave.”

As for what this period of reflection has taught him, McEwan argues that the crucial difference between when he started writing and today’s publishing world has less to do with changing social mores and more to do with the advent of endless technological distractions in the form of the internet and social media. “There was more solitude in the Seventies,” he says. “There was more space for daydreaming, so it seems from this perspective. The world didn’t seem so crowded, noisy and intrusive. But I feel as free to write now as I did then. Nothing has got in my way.”

Ian McEwan and the BBC Symphony Orchestra is at London’s Barbican Centre on 31 March