I recently tried a game that generates NPC dialogue with an AI chatbot, and within minutes I was arguing with a hard-boiled cop about whether or not dragons are real. "Large language models" like ChatGPT are unpredictable, habitual bullshitters, which makes them funny, but not very good videogame characters. Hidden Door, a company founded by long-time AI developers, says it can do much better.

I didn't get to play Hidden Door's game, which is really a platform, but I spoke about it for an hour with founders Hilary Mason and Matt Brandwein at the Game Developer's Conference last month. What they say they have is a way to generate multiplayer text adventures set in existing fictional worlds—like Middle-earth, for example—that can respond to any player input and tell structured stories with surprises and payoffs that, unlike so many AI chatbot conversations, actually make sense.

How it works

It takes a lot of work to build a product around this tech. And a prompt is not a product.

Hilary Mason, co-founder

To emulate a fictional world, Hidden Door trains its machine learning system on the setting's source material, which could be all of the Lord of the Rings books and appendices, for example. (This would be something they've licensed from a copyright holder, or that's in the public domain.) With help from a general language model, Hidden Door could then generate Tolkien-esque text that would probably include lots of references to rings and orcs and hobbits. Without constraints, though, the bot might just say "behold!" a lot while telling you that the government invented birds. This is where the work of turning a predictive text generator into a storyteller begins, and surprise surprise, it requires human design and writing, just like any other game.

Using a combination of AI trained on public domain fiction and manual work, Hidden Door says it has created a "story engine" that can mix and match storytelling forms with situations and characters to produce dynamic adventures for multiple players, each of whom controls a character with text commands.

...Setups, payoffs, nested arcs, like subplots: they're explicit data structures that are tunable.

Matt Brandwein, co-founder

"We pre-generate, and handwrite in some cases, bits of narrative in the engine that are tropes," Mason told me. "So, we have one for a bar brawl. That trope, a bar brawl, often involves a found weapon, somebody who's inebriated. And so we're able to take that narrative, and then 'found weapon' becomes something that can bring in other bits of narrative, like what do you make a found weapon out of? You grab a bottle."

There are "tens of thousands" of these manually written or edited tropes, Mason says, and "they get pulled together dynamically" to build stories that, if all goes well, should feel like they fit into the fictional world being emulated, both in writing style and in the kinds of stories being told.

"We explicitly model narrative arcs in a variety of ways," said Brandwein. "So, setups, payoffs, nested arcs, like subplots: they're explicit data structures that are tunable. Is this a three act kind of author? Is this some other kind of author?"

In some cases, the system must be strictly constrained by the licensed material: SpongeBob is a vegetarian, Mason and Brandwein have learned, and so any SpongeBob story generator would have to respect that. Mason described "rules" or "laws of physics" that they define for the worlds. Until we can try it ourselves, we're taking her word that this actually works (it's not an easy thing to QA test, she admits), but as examples: "Is there space travel? Are there laser guns? If it's Star Wars, somebody has to say 'the Force' every scene, or it isn't Star Wars."

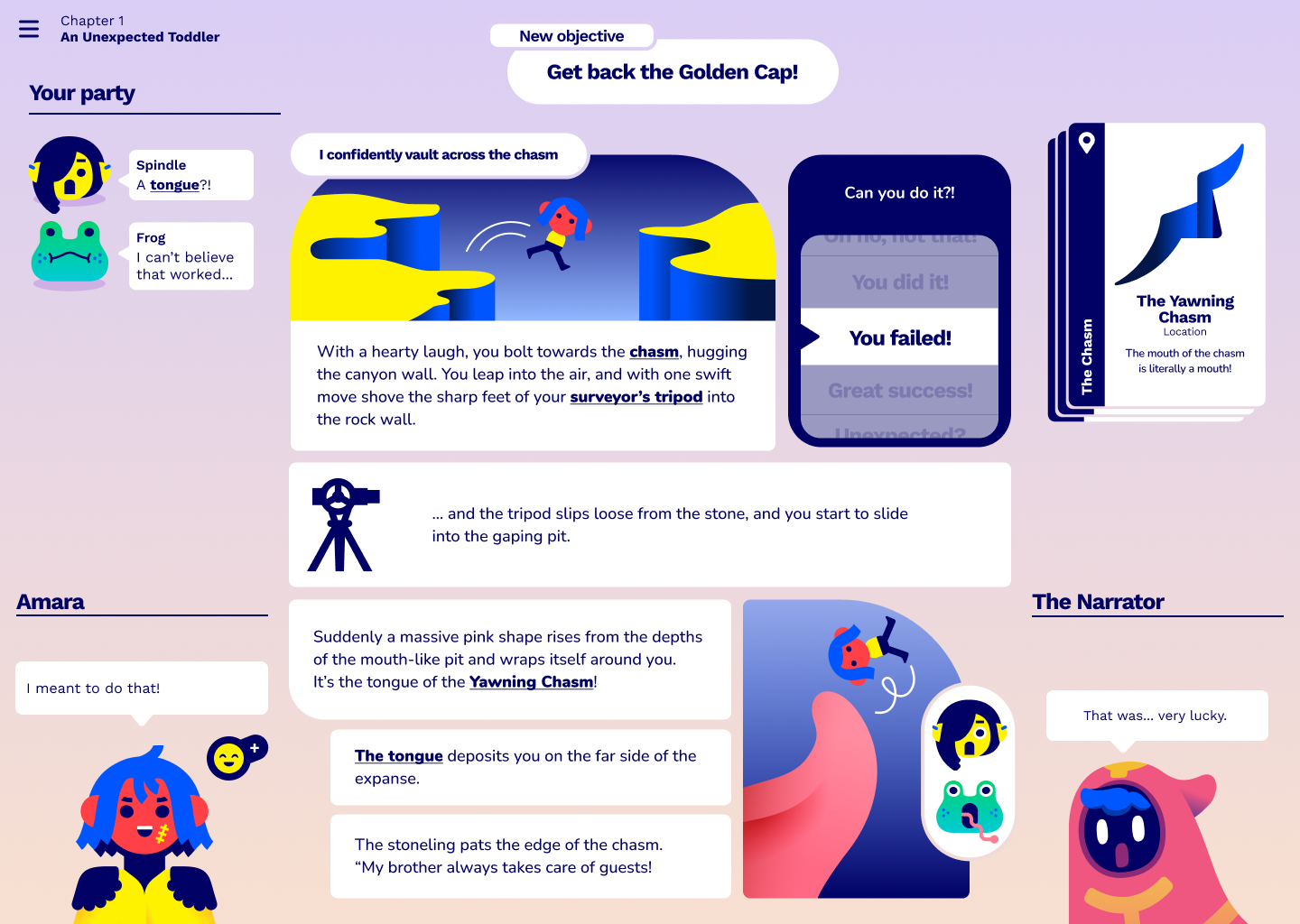

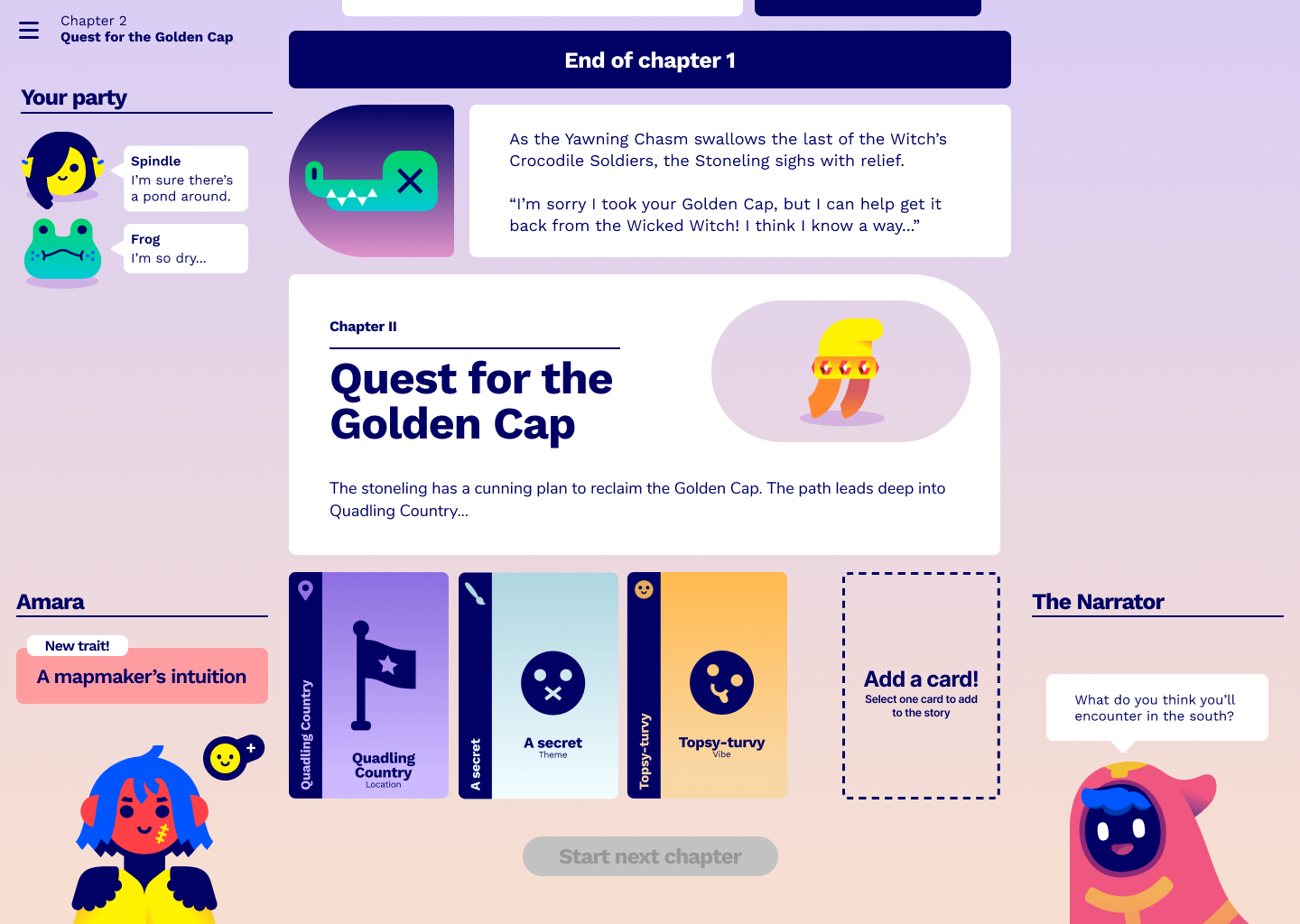

How it plays

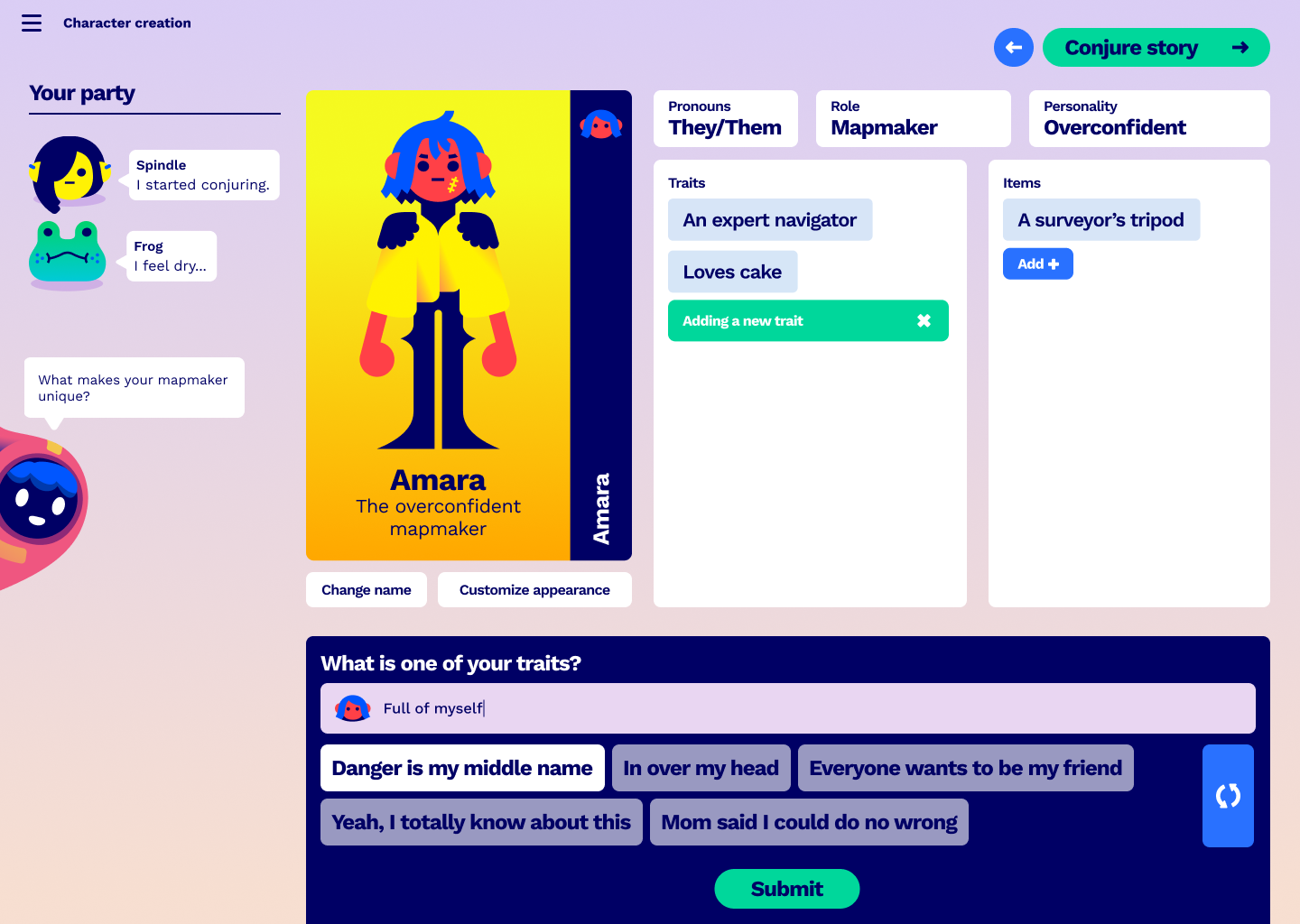

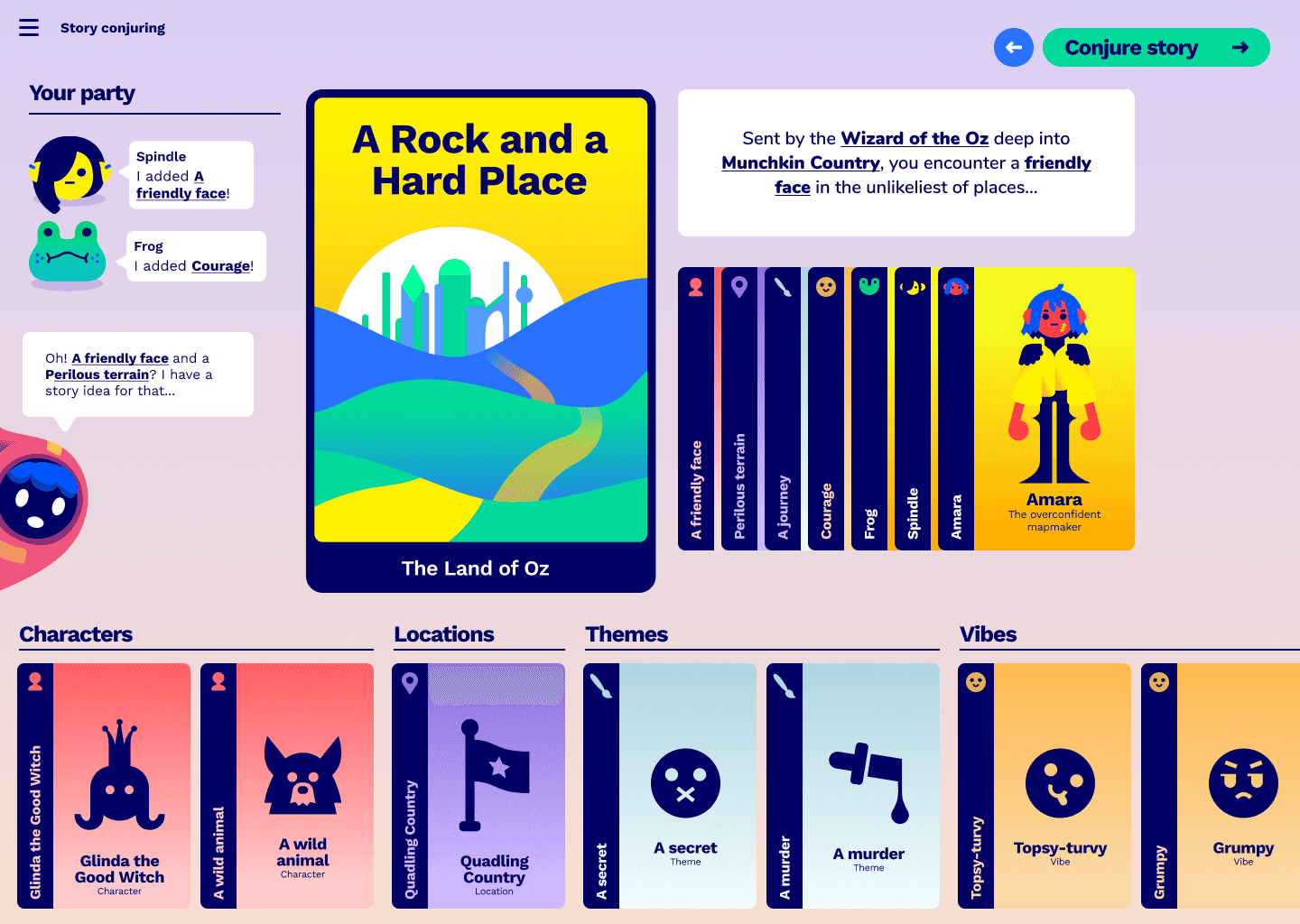

Players create characters by assigning descriptive traits—there are no stats—that will come into play as context dictates. The host can also customize the story that will be told with cards which represent characters, locations, themes, and "vibes," some of which may have been generated by a previous playthrough. A few examples of themes and vibes: "a secret," a murder," "grumpy," "topsy-turvy."

...Every couple of beats, there has to be a moment of surprise. How much surprise? How far out on the distribution do we want to go?

Hilary Mason

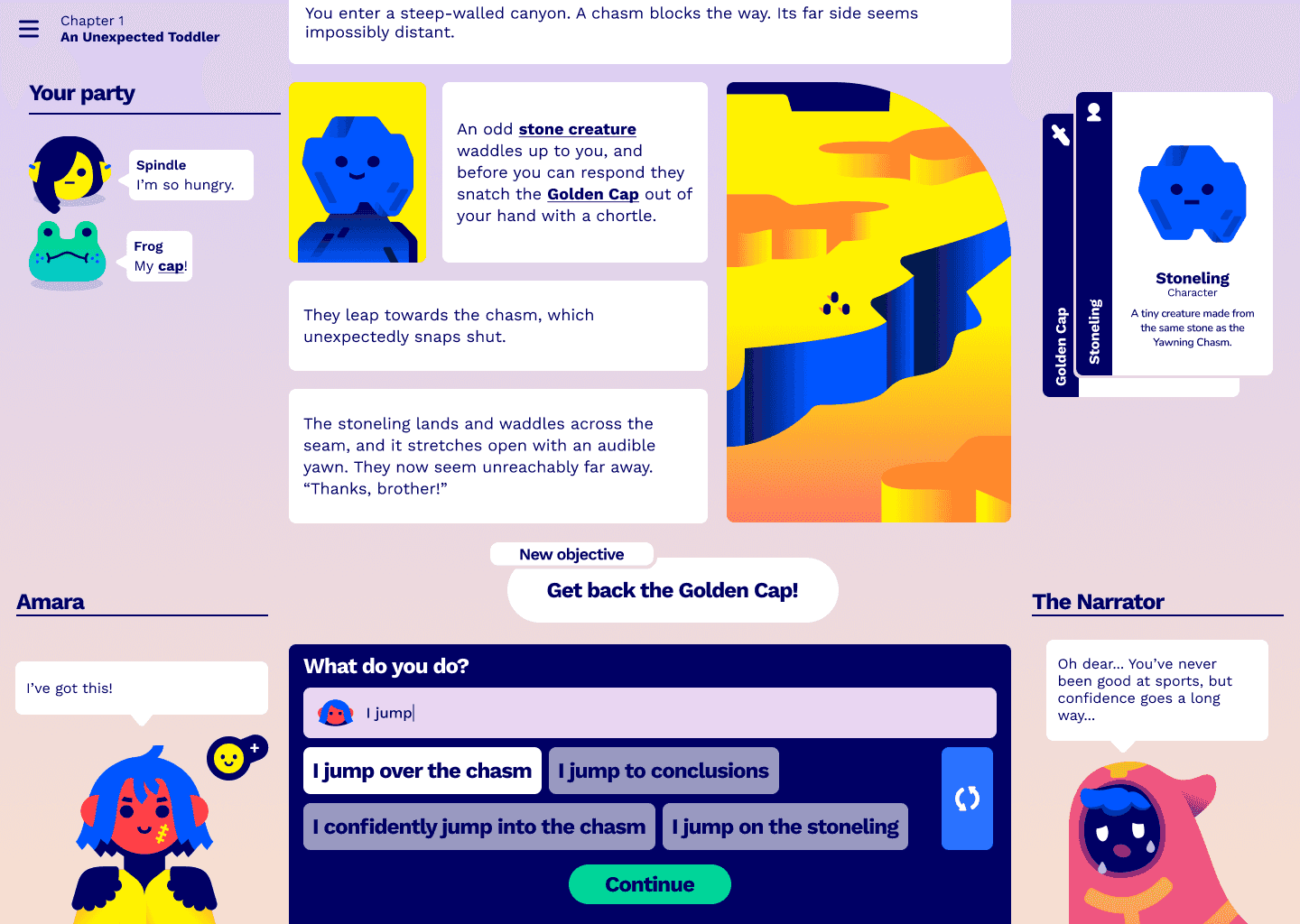

When the game starts, the story is told through short blurbs of text, like a DM describing situations, and players respond by typing into a search box and selecting a suggested snippet of input—similar to the way Google suggests search terms.

"Our system supports plain text entry, but we found out in testing, that's actually not a great experience," said Mason. "People have writer's block, or they can't spell stuff, so we've ended up with this interface where you can put in an emoji, you can put in words, and it will generate sentences out of what you're giving it that you play off."

The idea isn't to limit what players can do—they can do "anything," Mason tells me—but to help them come up with their next move by giving them phrases to toy with, some of which might surprise them. If everything works as described, the engine will respond sensibly to any input.

Because players can direct their characters to do anything, one of Hidden Door's big challenges right now isn't preventing the storytelling bot from going off the rails, but deciding how much it should try to keep players on the rails. A child playtester's response to encountering a mailbox was to tickle it, for example. Should the mailbox come alive and send the kid to a magical world of talking mailboxes? Or should it just be a mailbox?

"Right now we're very focused on making the story very compelling, and part of that is tuning," said Mason. "You could think of our engine, on the one hand, as something that can predict for any story what ought to happen next based on the underlying data. So we are therefore very well set up to create the most boring stories in the history of stories, because the most common thing would happen and happen. But we put a dial on that, so it's tunable. And something our game director spends a lot of time on is thinking about how, every couple of beats, there has to be a moment of surprise. How much surprise? How far out on the distribution do we want to go? If a player says something clearly indicating they have no interest in this story thread, do we drop it, or do we route them right back around to it again?"

AI hype vs reality

We believe people are creative. Machines are not creative.

Hilary Mason

Especially during this period of early ultra-hype, there's a natural skepticism around AI products that promise to do things computers have never done before. Finding the right language to describe them remains difficult—the phrase "artificial intelligence" itself is an enormous overstatement—and Mason says she's right there with the rest of us in thinking that all the hype is making things messy.

"There is so much hype around [AI] that people are speeding," she told me. "They think the first 90% has been done, and the last 10% is going to happen fast, and it's not. It takes a lot of work to build a product around this tech. And a prompt is not a product."

Today's machine learning research has also been generating ethical problems about as fast as fake selfies of our friends, and Mason isn't a stranger to them, either—she co-authored a book on ethics and data science that was published in 2018. Among the problems she's considering now are how to counter biases, which are inevitable in English language models trained primarily on American culture, and what kinds of content to allow or not allow on the platform.

One of the public's really big problems with AI right now, particularly when it comes to image generators, is the unapproved use of material on the internet to train them. Behind the scenes, Hidden Door does use a large language model that was trained on material available publicly on the internet. The ability to do that has been "taken for granted" for the past 15-plus years of machine learning research, Mason says, and she doesn't know where the world's going to land on it.

The identifiable stuff Hidden Door uses—writing styles, fictional worlds, visual art—will be paid for or come from the public domain. They do some art generation to represent characters in the stories, for instance, but it only remixes the work of their in-house artist.

"We believe people are creative," Mason told me. "Machines are not creative. Machines are an assistive technology to help facilitate that creation and that social experience."

Hidden Door's first game is based on The Wizard of Oz, and they hope to license contemporary fiction, and possibly work with authors to create original adventuring worlds. The company hasn't nailed down its business model yet, but its founders say the plan for now is to make the games free-to-play, possibly with paid enhancements.

Even if Hidden Door's games work as promised, it could turn out that multiplayer text adventures just can't attract a big audience with or without popular licensed settings. But fanfiction is popular, and hanging out in Discord is popular, and against all odds, D&D and other tabletop RPGs are popular in 2023. It might be exactly the right time for something like this, and I could see myself playing, say, Star Trek: The Next Generation missions with my friends, but only if they actually captured the tone of the show and involved entertaining problem-solving. A bad outcome for Hidden Door, I think, would be the games feeling like novelties rather than experiences that match the depth and imagination of tabletop roleplaying. Prodding a robot to see what it does is only fun temporarily.

Although Hidden Door's methods are new, the quest to build a software dungeon master is an old one. Procedural generation was used to create surprise and variation in some of the earliest games, such as 1980's Rogue, the game that roguelikes are like. With Left 4 Dead, Valve introduced an "AI director" to strategically, unpredictably hurl zombies at players. Dwarf Fortress generates an entire made-up history of civilization. Wildermyth, which we named the best RPG of 2021, tells procedurally-generated tales of adventurers who age, have children, and retire. Whether or not Hidden Door itself succeeds at using modern machine learning research to advance this quest for an artificial DM, it seems improbable that no one will, given the capabilities we've seen so far.

Hidden Door's first attempt, its Wizard of Oz game, will go into beta this year. You can sign up for the waitlist to try it on their website.