Citizen Sleeper—the original one—might be one of my favourite games ever, and it's for a lot of sentimental reasons. I played it right before getting this job, moving into a new apartment, and starting what is essentially a new life for myself, and boy did it hit dead centre.

For the uninitiated, Citizen Sleeper sees you occupying the body of a sleeper—a synthetic, failing body in a universe where AI is outlawed. A sleeper has a real person's consciousness uploaded to it as a legal workaround, plonking a living, feeling being into a body to make them work until they fall apart. So, naturally, you run away.

It's a game about carving out a home for yourself in the unfamiliar and hostile, and I love it dearly. Which is why I'm both delighted and baffled to say that my favourite thing about Citizen Sleeper 2 so far is how it's going to feel almost completely different.

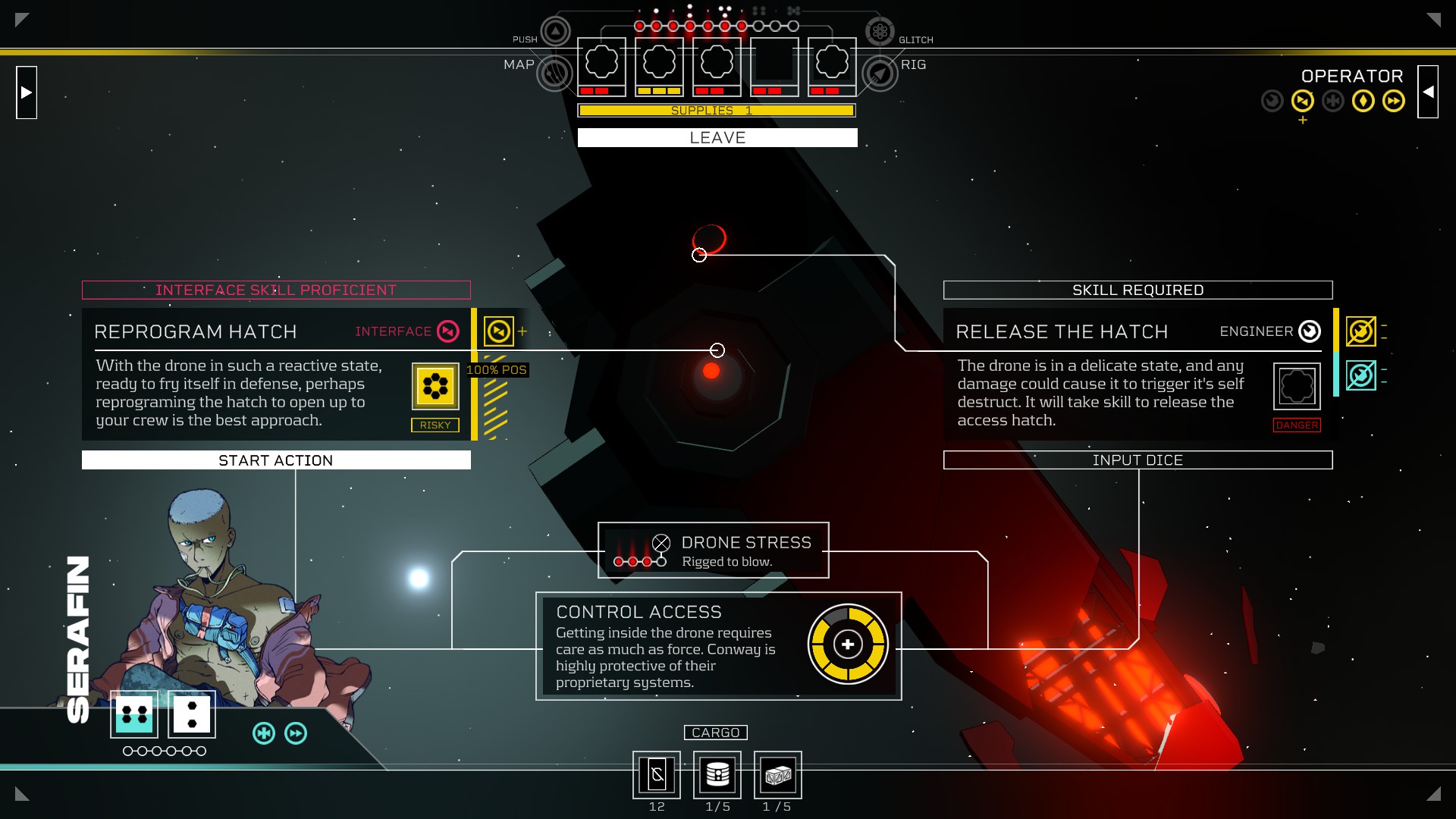

I was able to play a short demo and talk to the game's creator, Gareth Damian Martin from Jump over the Age. In it, I assembled a crew, took my rig out to a defunct drone, and spent the next half an hour with my heart in my mouth juggling stress and trying to disarm it.

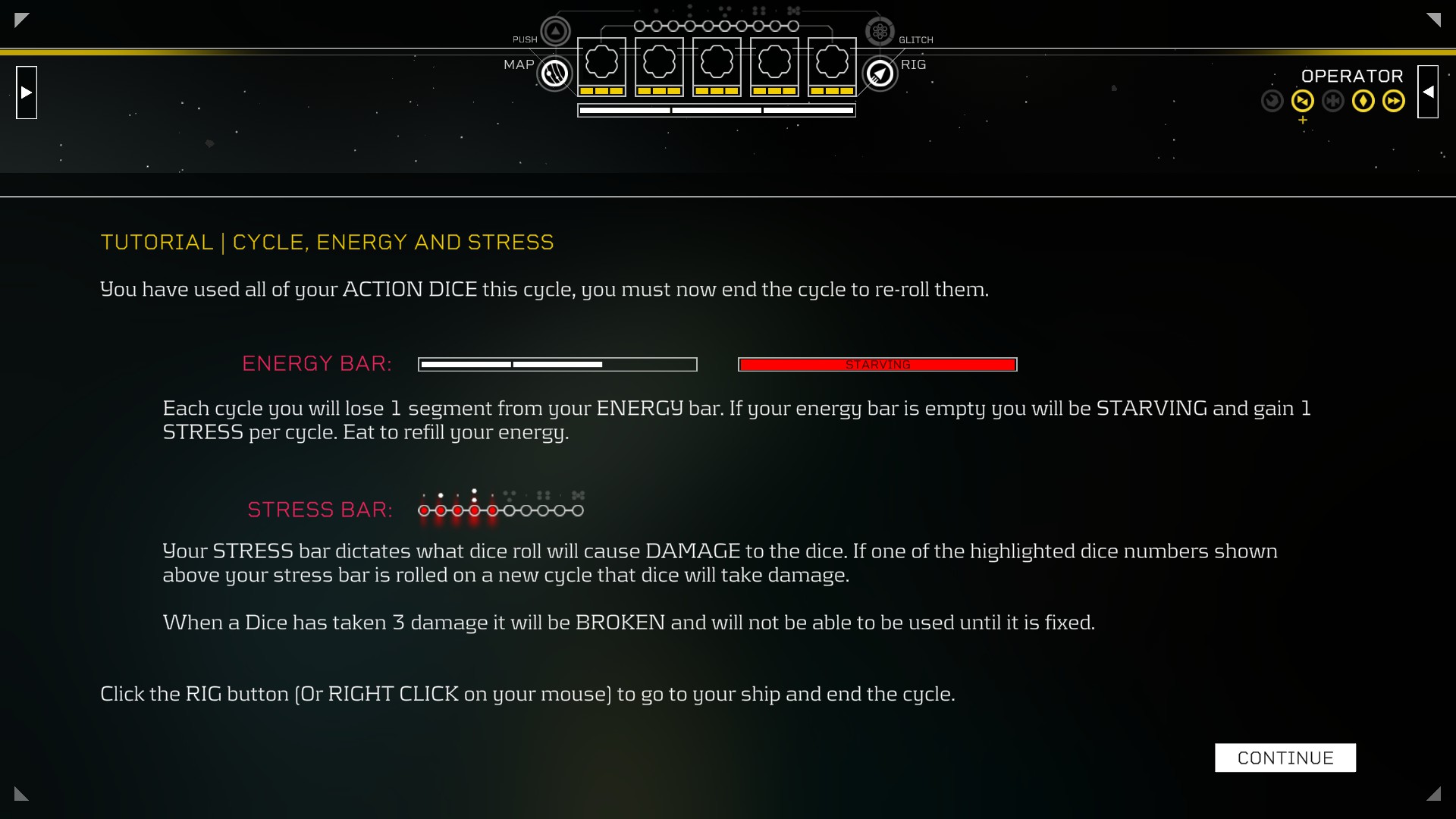

There are two major inclusions to talk about with Citizen Sleeper 2—Stress, and contracts. The newly-incorporated Stress mechanic essentially works as follows.

Failure states and ending cycles while starving can build Stress. The more Stress you have, the bigger chance you have to damage your dice: "[On] full stress, if you roll a [one to five on the die] you take one damage," Martin explains to me. "When you empty the health bar there, it breaks the die, and the die can't be used anymore." This is a problem, because your dice are your means of interacting with the world of Citizen Sleeper—if you can't roll a die, you can't do a thing, and you'll fall further behind.

The goal with Stress, primarily, is to encourage players to take devil's bargains while out on contracts. Contracts are small missions that form the "meat and veg" of Citizen Sleeper 2: "It's much more unpredictable, and stress is all about pushing your luck"—literally. Each class in the game comes with its own "Push" mechanic, which lets you gain stress for a boost.

I had exactly that kind of experience in the demo. My Sleeper was able to gain a point of Stress to reroll their lowest die. While out on my first contract, I was one bad roll away from disaster (contracts also have Stress bars, and when you fill those out by beefing it, you fail the entire mission). However, I still had my own personal pool of Stress to spend—all of my dice were pretty damaged, but I took the gamble and turned one of my dice from a one to a six, which gave me an assured win. If I'd rolled low, I would've been just as screwed with only more Stress to show for it.

These contracts play out a little like the DLCs in Citizen Sleeper 1 did—they're bite-sized, but they allow the game to set limited stakes that completely box you in: "They're kind of like episodes in a show like Cowboy Bebop and Firefly," Martin says, adding that: "Stress is more of a problem during contracts—when you go on a contract, you can't recover stress … when you come back to the station, you're much more in recovery mode."

This is really fascinating to me, since one of Citizen Sleeper 1's strange qualities was that, despite the overbearing and dystopian situation, you can still get comfortable. This sequel, however, means to keep the pressure on: "You might actually get to a stable point where you start to feel like you're really handling contracts, and then you might slightly misjudge your luck or get overconfident—it's very easy to enter a death spiral and end up in a really difficult situation."

That's not to say disaster will lead to death, though: "You'll have to recover from that, the game is not gonna be like 'game over, don't worry, try again' … I like to keep players playing, I don't want to give them game overs, I want to keep the story going because I think that's most interesting."

Having played with some contracts, I can already see that intention working out spectacularly—and while I'll miss the first game's gradual drift into comfort and homeliness, I think that Citizen Sleeper 2's emphasis on smaller, but more intense mechanical dramas is both incredibly compelling and a breath of fresh air.

See you, space cowboy...

"I'm not really interested in just making more of Citizen Sleeper," Martin says of the contract system, which they believe helps them tell a "fundamentally different" story. They add that the sequel "felt like an opportunity to bring a few more of those really cool tabletop mechanics that we know and love into videogames, where they should already be."

As someone who has played a lot of TTRPGs in my time, I can't agree more with Martin here—most RPG systems that have made their way into games are a lot more combat-focused, which does make a ton of sense. They're a lot easier to translate than narrative-based rulesets, because you're essentially just plugging in a set of mechanics that make the fighting go smoothly, which is something a videogame RPG already needs to have. Baldur's Gate 3 is a 1:1 translation (with some funky homebrew magic items and tweaks), while almost everything good about its narrative mechanics come from Larian Studios itself, rather than the system it's built upon.

I'm not really interested in just making more of Citizen Sleeper.

Gareth Damian Martin

Still, there's so much untrodden ground—and that's exactly the kind of space Citizen Sleeper 2 is trying to walk. Martin tells me that they've taken inspiration from the dark fantasy heist game Blades in the Dark, the sci-fi horror TTRPG Mothership, and Heart, a game about delving into a nightmarish undercity, among others: "I had so many more things I wanted to do," Martin adds. "So I was like—okay, let's make a sequel and see how it goes."

It's not all going to be cosmic horrors and pressure-cooker stakes, though—Martin says that "the game is also gonna have an end-game state like Citizen Sleeper did, as well … as the game goes on it opens up, and you have a lot more freedom to pick and choose, and fly around where you want to."

'I won't give you the dragon money, then'

The TTRPG lifeblood, of course, runs just as thick with Citizen Sleeper 2 as it did the first game: "When I approach [designing] RPGs," Martin notes, "I try not to think too much about videogame RPGs—I try to think about how I run tabletop games, and the things I like there."

That's not to say Martin doesn't look at video games at all—both for inspiration, and for things to avoid. "Mass Effect 2 is like an anti-reference for this game," they add. "I really like Mass Effect 2, but there are a lot of things I really dislike about it as well."

Martin outlines a general malaise with the 'you're so special, you're the boss' power fantasies of mainline RPGs—and I can't help but find myself nodding along. I mean, don't misunderstand me, I like being the chosen one just as much as the next guy. But failure, pressure, and struggling is also really compelling—it's why horror RPGs like Darkest Dungeon and Fear & Hunger have found their respective audiences.

The problem is it's like—do you wanna be a cop, or do you wanna be evil. Like—that's not a choice. That's not a binary in the real world.

Gareth Damian Martin

"I think with Mass Effect, my problem's always been the kind of military hierarchy of [the game] … You're kind of everybody's boss, and you can also order them to go on a date with you, basically? There's lots of very dodgy stuff." Chiefly among the things that bothered Martin was the Paragon/Renegade system, which they describe as offering a choice between "agreeing with authority" and "bad": "The problem is it's like—do you wanna be a cop, or do you wanna be evil. Like—that's not a choice. That's not a binary in the real world."

Martin, however, is also happy to point out when games buck this trend: "I think my favourite quest in all of the Witcher 3 is the old guy who says that he's seen a dragon. And you're like—you can't have seen a dragon, and he says 'I definitely did', and then you go and you find a wyvern. You come back and you say 'it was a wyvern', and he says 'oh, well I won't be paying you the dragon money, then.' And my game is just… all of those quests!"

This phrase, which I will be stealing, comes from a desire Martin has to create interesting scenarios out of denying the player what they want—a kind of "no, but" style of design. "I guess it's the GM in me that I'm naturally oriented to not always giving people what they want … and so especially as the whole game is that 'I won't give you the dragon money' type thing, I also don't, well, want to give people the dragon money."

The dragon money eats its own tail, though—as that redirection of expectations leads us right on back to TTRPGs: "One of these things that was so exciting with Citizen Sleeper 1 was just getting people on board with these systems that had been tried and tested in tabletop games, but people in videogames haven't played them before … like yeah, you can do this! And there's loads of it—there's so many things like this and they're all really interesting … Knowing that there is an audience [now] gives me a lot of energy to mess with it, in a way."

Ultimately, I get the feeling that Martin wants to give people a way to—in the same way that anyone who has played a breadth of TTRPGs will tell you—try something other than D&D: "I want people to say I finished Baldur's Gate 3, and I want them to say 'play Citizen Sleeper 2'. That is what I want, I want to engage that audience … I think we're having a really great moment for the interaction of TTRPGs and game RPGs, and I'd really like to say: 'Hey, look, Citizen Sleeper 2 is right here, and it's doing all of this stuff'."

As a long-time D&D DM who has just started to really dig into alternate systems these past couple of years, I can't help but agree—even if Dungeons & Dragons is your favourite game, you'll get better at running it by looking at what other systems are doing, too. It's my hope that games like Citizen Sleeper 2, which'll be releasing sometime next year, will have a similar effect on the videogame RPG landscape as well. I, for one, can't wait to be stressed out of my synthetic mind.