Alan Schaller’s photography journey began while he was still pursuing a career in music production. However, he decided to express his creative vision through the camera lens rather than a mixing desk.

Alan Schaller’s Metropolis book elevates cityscapes to an art form, playing with light and perspective. It features 150 black-and-white images from some of the most visited cities in the world. Metropolis is published by teNeues, priced £75 /$100.

With a precise sense of light and composition and a keen eye for capturing fleeting moments with a narrative, Schaller soon established himself in the industry. Starting with a series of images taken on the London Underground, he later photographed people on the streets of cities such as New York and Tokyo.

As one of the co-founders of the Street Photography International Collective (SPi), Schaller is passionate about promoting talented and unrepresented photographers. He enjoys sharing his knowledge with aspiring photographers through his YouTube video tutorials, giving an insight into various techniques. We met up with Alan to find out how to capture that perfect moment and also spoke to him about the inspiration behind his new book Metropolis, published by teNeues, in which Schaller uses minimalistic images of urban architecture to visualize the idea of being isolated and lost in the modern world.

Interview

Street photography is known as an unpredictable genre but how unpredictable is it in your opinion?

Yes, it’s unpredictable – but I think the more experienced you get, the more you can try and, not necessarily predict, but pre-visualise what might happen. I tend to try and control as much of the image as I can. There are controllable factors, for example, where I am standing to frame the scene. I always ask myself what could happen – or what is it I want to see happening? As I progressed through my career, I’ve learned what I want and what I don’t want. It helps cut down the randomness of the street and gives me a better chance of achieving a decent picture as well as some sort of consistency. For example, let’s say we’re on the London Underground, there’s a lovely stairway and the lighting is perfect. I’ll stand there and wait for a person to enter the scene. If the wall is white, I am waiting for a person wearing dark clothes, if the wall is dark, I will wait for someone wearing light colors to arrive.

Have you ever missed capturing the moment? Or do you always carry a camera with you?

I used to joke that the only places I wouldn’t go with the camera were in the sea or in the shower, but now I have a waterproof one, so I can do that too. Sometimes, I go out and don’t even plan to shoot but it ends in capturing stuff that happens. However, it’s not a burden, I love it. I’ve always said that I’m extremely lucky that I’ve made this into a career and if it wasn’t, I would still be looking for these things.

Being with non-photographers on the street is a slightly different matter. I always have a Kindle in my bag to give them something to do in the meantime, and to show them that I’ve thought of them. My camera is always there, always on – it’s not just for show. I keep it on and pre-focus to 1.2 metres. I identify the scene first and then I do something I call fishing. It’s like being a fisherman instead of a hunter. I drop the line in and wait for the big fish, whereas a hunter would stalk around. It’s always worth having the camera there.

What are the kinds of things that trigger your photographic instinct?

I remember when I was younger I was on a date and this lady was not very happy with me because I was obsessed with this table next to us. It was interesting and had really nice lighting, so I feel I’m aware of everything that’s going on around me. It’s hard to explain but once I start seeing it, I am focused and driven to it.

I use a lot of everyday objects in my photography, so there is a lot that can make me stop and trigger the thought that there is a photo here. I think it’s a skill to observe and analyse the surroundings like that. That’s what has become clear to me as I am getting into fashion photography now. However, sometimes it’s funny what gets me to press the shutter button.

When I was in India, we were going to a spectacular temple, but the best scenes I captured were on the way there and on the way back. It’s the most unexpected times, the little moments that happen. The same happened in Paris at the Eiffel Tower. I was at a hotspot from where everyone photographs the tower. I turned around and there was a staircase so I took this picture. It has nothing to do with the Eiffel Tower but it’s my favourite shot that I’ve taken there.

What was your first camera when you started the journey?

One of my first cameras was a Canon 70D. It was a cheap option but it had too many features. Then I made the decision to get a Leica – for me, that’s the ultimate camera brand. I’m interested in things that are well-made, regardless of what it is.

I couldn’t really afford one at the time but managed to get enough money to buy one. It was such a crazy thing to do. I’d just got a mortgage and then spent like £9,000 on a camera and lens for a hobby. I felt sick, like actually physically sick. I didn’t open the box for a couple of days so I could still take it back. I was worried and wanted to earn the money back.

I thought I could help with a few weddings – but I wasn’t thinking about making a career. But it turned out to be probably one of the single best decisions I’ve ever made in my life. After that, things started going quickly for me and it was all organic. I was doing as much photography as I could while I was still working full-time in music. I bought a Leica M Monochrom Typ246, then an M10 monochrom and now I’m working with the M11 Monochrom.

What is the best part of photographing with a monochrome camera?

I’ve got used to the Leica M’s stylish shooting. I’m spoiled with my monochrome sensors – color sensors don’t really do it for me, or at least, it’s a fight. I’m used to this way of shooting. Having the tonality, the black and white look but also the highlight retention is what I like. It’s a huge thing because I do a lot of backlight shooting, so it gives me different options on how to expose a scene.

On digital, you have to nail this and under-expose a lot, whereas film reacts a little differently. When the subject is backlit, you get some lower levels of contrast compared with digital and when a scene would suit that more than I am doing it. It’s not essential but it’s the things to consider to fine-tune the look I want.

Would you say that it is essential for a photographer to be in total harmony with their equipment?

Some people say the camera isn’t important, that it’s all about the photographer, but I think this is a stupid way of looking at it. Ask a professional chef if being dropped in a random kitchen is good for them, probably not. Anyway, it’s that kind of thing. Yes, I can produce my look on any camera, but I’d much rather have my setup because I understand

it better. For example, with my 24mm lens, I understand its characteristics, when it will flare, when it won’t and I know how to focus without really thinking about it. I’ve shot with the 24mm and 50mm for about six years now and sometimes I’m still surprised by some things, so I am still learning. Learning what it’s all about and bonding with your gear makes a difference in capturing the final moment.

What was the visual aspect you were aiming for when creating the images for your new book Metropolis?

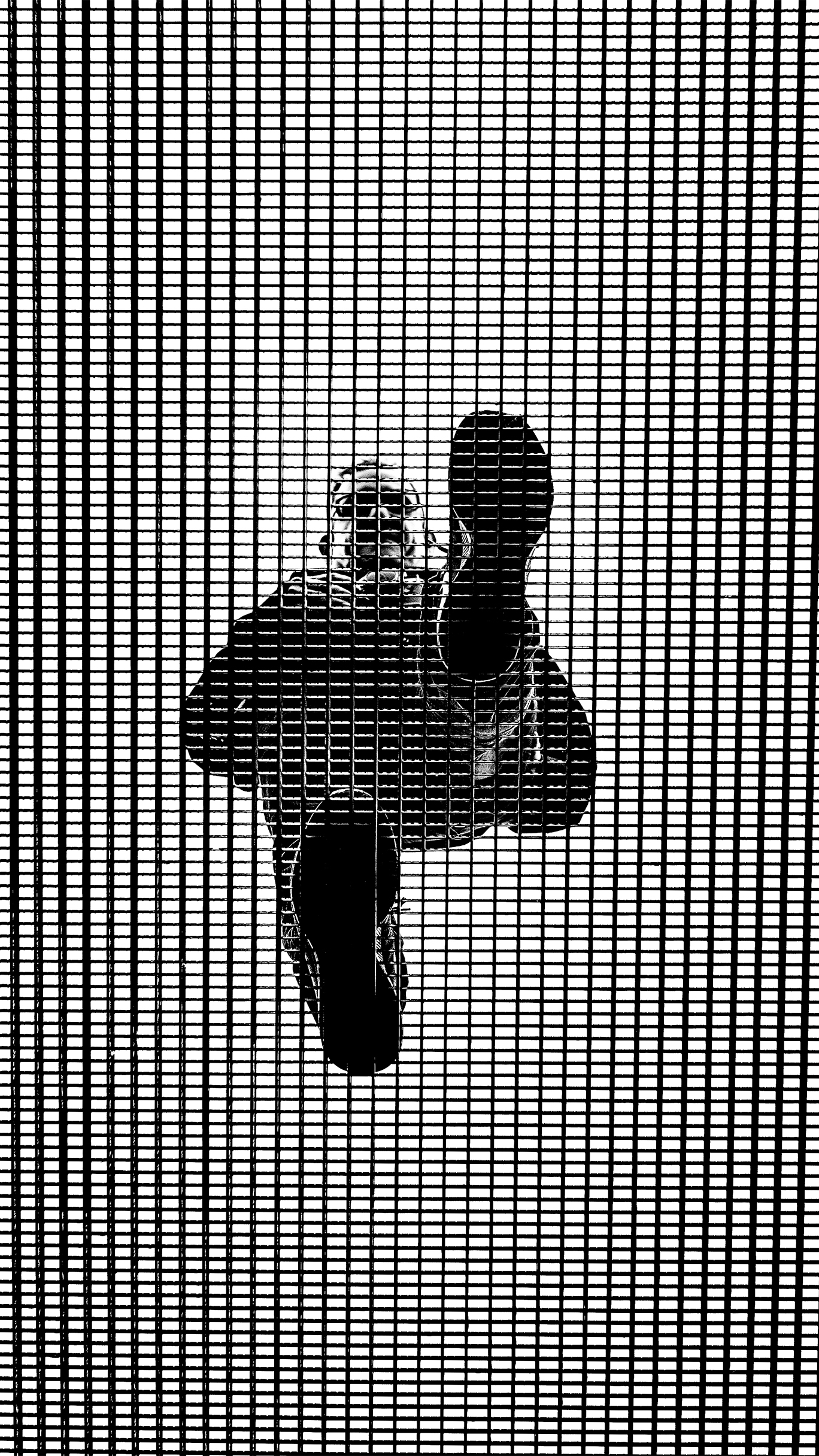

It has a particularly strong style. The book is themed around urban isolation, so I chose images that expressed this feeling and atmosphere. I wanted to convey the idea that we’re more connected than ever, through things like the internet, but at the same time less connected. Big cities especially can be very isolating places. I felt that many people can relate to being in a busy place but feeling alone and that everyone feels this but pretends to be fine about it.

I used to do this thing where I printed about a hundred small images and I put them in a shoebox. I’d put them all out on the floor, look at them and group them into sets. Eventually, one of those sets was five images that had been shot over a year between them showing a lot of black negative space. I hadn’t shot those on purpose like that, it was just an idea, so I pinned these up and I was like, ‘Right, I’m going to try and make another five’, and so on. A friend of mine came around and I asked him what he thought. He said that these pictures look like people dwarfed by the world around them. They look tiny, it’s like they’re being oppressed by the architecture. I was like ‘Thanks! That is it!’ I felt that I could identify with the message.

So how much were you involved in the layout of the book?

I don’t think I’ve talked about this but the layout and curation were done in a special way. We created a tonal graduation throughout the book. It starts off with the darkest images, ends with the lightest ones and, in the middle, it’s kind of grey. The publisher teNeues said that they don’t think anyone has done that before. I don’t know much about bookmaking honestly, but I’m learning. There are so many things around photography to learn, like doing exhibitions or choosing printing paper but also the business side of it, licensing, contracts and more. It’s a never-ending process and I love it.

Do you have any tips or advice for photographers who want to work on a longer series or even a book?

It’s important to have a theme that’s relatable. I think photographers often make work for other photographers. It’s like ‘Look at the silhouette I created’ but the average person won’t care about this silhouette. But if you use a silhouette to tell a story that’s interesting to the viewer, they can understand and appreciate the technique.

There is a saying that one single picture can say more than a thousand words and I like the fact that you don’t need to always understand everything. Even though a lot of those pictures for the book were taken with a photojournalistic edge or with the intention of telling a story, they still just scream something on their own.

Hopefully, this is a piece of work that, 50 years from now, I can look back on and be like, ‘Yeah, that is how I felt back then’. However, maybe next time, I’ll do something a little more cheerful.

Schaller's camera history

Canon EOS 70D

Leica M Monochrom (Typ 246)

Leica M10 Monochrom

(now) Leica M11 Monochrom