When Triumph re-formed briefly to play 2008’s Sweden Rock festival, there was just one problem: they’d barely spoken to each other in 20 years. Collecting gongs at an awards ceremony had brought the Canadian power trio back into each other’s orbit, but now Rik Emmett (guitar), Mike Levine (bass) and Gil Moore (drums) had to unpick a Gordian knot of bad blood and hurt.

“Initially it was awkward as shit,” Emmett tells Classic Rock today, at home in Burlington, near Lake Ontario. “We met at a coffee shop, with a mediator, and he was like: ‘If you guys can bury the hatchet, I can get you into the [Canadian Music] Hall Of Fame.’

“But the big catalyst for me was that my younger brother Russell had died in 2007,” Emmett continues. “Just before he passed, he said to me: ‘Rik, nobody in the world is a bigger Triumph fan than me, and I would love to see you guys back together.’ I thought: ‘You son of a bitch, Russell! You’re dying of cancer, and now I have to try this!’”

As documented in Banger Films’ 2021 biopic Triumph: Rock & Roll Machine, Emmett had broken his bandmates’ hearts when, seeking new musical challenges, he left in 1988. Burying that hatchet wouldn’t be easy. “Each of us had grown to believe our own anger and bitterness,” he says. “Then you think: ‘That’s fuckin’ stupid. Let it go.’ Pretty soon it was as if we were on the road in Iowa again, just hanging out and cracking jokes.”

Sweden Rock, meanwhile, proved great fun. And when Brian Robertson, formerly of Thin Lizzy, approached Emmett to tell him how much he liked Strung Out Troubadours, Emmett’s 2006-formed guitar duo with fellow Canadian Dave Dunlop, high jinks ensued.

“This big sweaty German guy had interrupted us really rudely with about fifteen albums to sign,” a smiling Emmett says. “Then later on Robertson noticed him asleep on a couch in our hotel lobby, and he goes: [decent Scots accent] ‘I’m gonna get that fucker!’ So the German guy’s snoring, and Brian sneaks up and writes ‘C*NT’ on his forehead with a sharpie. Poetic justice!”

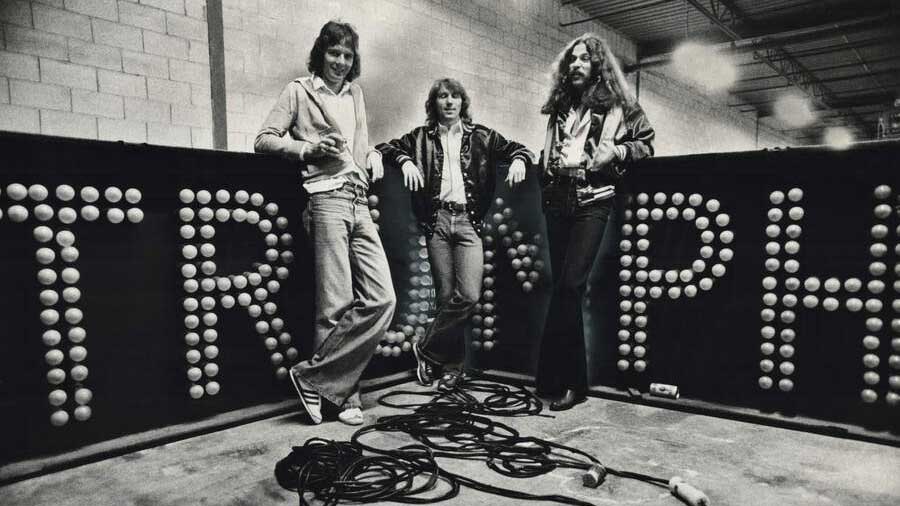

Prior to Triumph forming in Mississauga, Ontario in 1975, Mike Levine and Gil Moore had played in a less succinctly named group. When Abernathy Shagnaster’s Wash And Wear Rock & Roll Band imploded, the ambitious pair decided to form a trio, and began scouting for the perfect foil. Blonde, square-jawed, a noted and versatile guitar-hero-about-town, Rik Emmett was in King Crimson and Gentle Giant-influenced prog band Act III at the time. Like Moore, he also had a great high-register voice, and they would go on to share lead vocals.

Levine’s recording engineer background and Moore’s long-standing PA-hire business showed their enterprise, and by the time they head-hunted Emmett they had somehow secured a sizeable Attic Records’ advance, which they waved under the guitarist’s nose. Emmett, still living with his parents, needed the dosh so that he and his girlfriend could rent somewhere together. He threw in his lot with the sharp-talking Levine and Moore, and Triumph was born.

From the outset, they put the ‘show’ into ‘showbiz’. Moore knew all about pyrotechnics – “Triumph would come to your town and blow shit up!” Skid Row’s Sebastian Bach has said – and used aircraft landing lights to bring early classic The Blinding Light Show to life. Moore would also hype up audiences with statements of intent. The very hirsute Levine, Emmett recalls, “looked biblical”, while Emmett himself, often shrinkwrapped in white or red Spandex, had ice-hockey pads on for protection.

“I’d injured my right knee in high school playing [American] football,” he says, “so I needed the pads when I was doing my Pete Townshend power-slides across the stage.”

On the record front, things weren’t initially so spectacular. 1976’s In The Beginning and 1977’s Rock & Roll Machine didn’t do that much to distinguish Triumph from party hearty also-rans. But by 1979’s Just A Game, Emmett’s writing in particular had become much more sophisticated. Rich in layered vocal harmonies, Triumph’s fine, gold-selling breakthrough took a year to make, and its title track called out the music industry’s ivory-tower dwellers. In the US and Canada, two more Emmett-written gems – Lay It On The Line and Hold On – quickly became drivetime radio faves.

Gil Moore’s straight-ahead rocker American Girls was great too, but its ‘I know how to treat a lady, who knows how to treat her man’ sentiments were more crotch than cranium. Emmett was no prude, and liked an American girl as much as the next guy, but he also sought purpose in life.

“I would look at people going apeshit at our concerts and think: ‘What are we offering them?’ If we’re going to be called Triumph, we need to give them some inspiration, something positive. When I wrote Hold On it was like: ‘Okay, maybe this is why I’m doing this. Maybe I can write songs that make people feel better about themselves.’”

It was this compassionate streak that led Triumph to be seen as “the good guys in an era meant for dirtbags”, as celebrity fan Danko Jones put it, recalling Triumph playing to 300,000 metal fans at 1983’s massive US Festival in San Bernardino, California. Dressed all in white that day, Triumph seemed to be the angelic antithesis of such celebrated dirtbags as Mötley Crüe, who were also on the three-day bill.

The perception that Triumph’s music was fairly wholesome – unlikely to contain backwards-masked messages advocating devil worship – was further cemented by another brilliant Emmett song from 1981’s Allied Forces. Fight The Good Fight mentioned ‘The good book’, while its altruistic, ‘take courage’ message was manna for Triumph fans facing all kinds of adversity. The song also suggested that Emmett might be a man of faith, a believer. True?

“My mom was a very religious person,” he says. “I was steeped in Christianity until I was about twelve, then I thought: ‘Wait a sec. I’m not buying into this idea of the Resurrection and an afterlife – I don’t want to be a hypocrite.’

“When I opted out it caused a big fall-out with my mom. I was her golden boy, singing first soprano in the church choir. My aunt Joan was actually dying of cancer when I wrote that song, and we talked about St Paul saying to The Corinthians you gotta fight the good fight. But my take on that was that it needn’t necessarily be a religious thing.

“These days I’m a secular humanist,” Emmett sums up, “but I still believe the human spirit is a very powerful thing. Question is, are we going to use it like Putin uses it, or are we gonna use it like, say, Nelson Mandela used it?”

By Allied Forces, Triumph were huge. They’d also made it over to the UK in support of their previous album, 1980’s Progressions Of Power. That album’s I Live For The Weekend remains the perfect precursor to Friday-night revelry. It was also Triumph’s first and only UK-charting single, peaking at No.59. This writer saw them at Glasgow Apollo that November for a thrilling night of retina-scorching spectacle. But Emmett’s memory of the tour is that they didn’t quite translate.

“The critics kind of hated us, and Kerrang! gave us a bad review,” he says. “We were a glitzy North American act with lasers. People went wild for that in America, but in the UK it seemed a little too much for some sensibilities [laughs].”

There was also the matter of that ‘other’ Canadian power trio. Triumph were endlessly compared to Rush, and Emmett understood why, but really, the two bands were very different animals.

“I think Triumph were reaching for the charts more,” says Emmett. “We worried less about recreating what we did in the studio when we played live. Rush were also more tight as friends, I think. Geddy and Alex had known each other since school, and in Neil they found a guy who shared their artistic vision. Triumph were friends too, of course, but it was more of a business relationship.

“I suppose the slight irritation that remains for me is that Rush were so huge and so unique that you just couldn’t compete with them,” Emmett adds. “Also, Rush had a fourth guy: their manager, Ray Danniels, whereas we managed ourselves, and that was always going to lead to problems.”

Prior to 1984’s Thunder Seven, a contractual dispute with RCA records resulted in Triumph buying out of their deal for three million dollars and releasing the album on MCA. The Sport Of Kings (1986) wasn’t plain sailing, either, with intra-band relations having deteriorated to the point that Triumph weren’t writing together. Accordingly, producer Ron Nevison was hired to try the ‘lets bring in outside writers’ approach that had been so fruitful when he produced Heart’s 1985 Top 10 smash What About Love.

“Ron wanted me to sing the songs,” recalls Emmett, “but Gil was like: ‘What? That’s not gonna happen in my band.’ I agreed with Ron, and felt that as the voice behind Lay It On the Line and Magic Power I was our best shot at getting back on radio, but that was never going to fly given band politics at the time.”

Pretty soon, Nevison was sacked from the project, and production of The Sport Of Kings was credited to Mike Clink and Thom Trumbo.

Triumph limped on for 1987’s Surveillance before Emmett jumped ship – “I knew we were going nowhere fast and I had to get out,” he says of the whole debacle. Levine and Moore then made the group’s 1992’s swan song Edge Of Excess with (then) hip young shredder Phil X, later of Bon Jovi.

Even today, Rik Emmett is careful to take care of business. After many minutes of Triumph chat, he briefly steers his conversation with Classic Rock towards his excellent new solo compilation Diamonds: The Best Of The Hard Rock Years 1990-1995, stating, not unreasonably, that “this is the reason you and I are talking today”.

Now 70, he’s in the process of putting radiation treatment for prostate cancer behind him. He also has arthritis in his hands, he says. “And that’s tricky, because it’s really cramping my style both literally and metaphorically.”

Following his time in Triumph, Emmett’s career opened up into broader, more imaginative channels. He made solo albums that explored jazz, folk, flamenco, and swing music as well as rock. He started writing for Guitar Player, was a cartoonist for Hit Parader magazine, and taught songwriting and music business at Toronto’s Humber College.

Emmett’s 2021 poetry collection Reinvention, meanwhile, marked him out as a guitar hero with different sensibilities to, say, Ted Nugent, and he has a second volume, Leaning Into It, on the way. “But the poetry is a bit like when I release a jazz record,” he says, smiling. “You’re immediately shrinking possible sales down to the smallest possible demographic.”

He also published his memoir, Lay It On The Line, last year. “I was never in it for the sex and drugs…” he writes at one point, again shrinking his demographic, but the book’s still a fine read.

What did he learn about himself while writing it?

“Maybe that for all the showbiz bullshit that’s gone down in my life, I adhere to a philosophy of humility more than anyone might imagine, while watching old footage of me in Spandex!” he says, laughing.

Now Emmett pauses, something occurring to him. “I remember meeting one of my heroes, Chet Atkins, in Nashville in 1979. A genius guitarist, obviously, but also the A&R guy who signed Elvis to RCA, and you can’t beat that. He was lovely, very humble. I thought: ‘When I grow up I want to be like Chet.’”

Rik Emmett’s Diamonds: The Best Of The Hard Rock Years 1990-1995 is out now via Deko Entertainment.