Imagine you are a single father living in a housing commission flat in New South Wales, and a case worker from the department knocks on your door.

You answer, and the case worker tells you she needs to come in. She got a call and report from your daughter’s school. It really is not that serious, but she will have to ask you and your daughter some questions. She also needs to talk to your other child, and she will need to take a look around the house, just to make sure you have everything you need. That’s fine with you, right? Reluctantly, with fear, you let her in. You don’t verbally say yes, but you nod your head. You are actually speechless that the department has rocked up to your place.

You watch her take notes as she opens the kitchen cabinets and refrigerator door, counting the food products available, looking at the bread to see if it’s gone out of date. You see her come across the number of beer bottles left in the refrigerator. You hesitate – should you explain to her why they are there, should you let her know people have been over? But then you fear this means overcrowding and neglect in her eyes. Should you let her know this? She has moved on, though, smelling smoke. You ask yourself, should you let her know that windows are open and the neighbours smoke next door and it sometimes comes in? The case worker begins to dramatically step over the toys that the kids and your nieces and nephews have thrown around the living room. She scribbles in her pad, taking notes as she walks by the sink, which is full of dirty dishes that you have not had time to clean – and, yes, there’s not much dish soap left because it is expensive and your payday is in a few days.

She walks into your bedroom, then your kids’ room in the housing commission flat, and then the bathroom, taking notes the whole time. The house is messy. You struggle with this. The case worker calls your daughter into the bedroom and asks you to instruct her that it’s OK to speak alone and that she should follow the case worker’s instructions and answer any questions she might have. Nine-year-olds may not feel comfortable speaking with strangers, of course. You follow these instructions, worried. You don’t even know your rights, but you are fearful by this point and walk back to the kitchen table. Your daughter then looks at you to see whether this is OK. She listens to her dad, always.

What choice do you have, really?

The case worker finishes with your daughter and now calls in your 11-year-old son. You want to ask what is going on, if you are free to go or better still if she would just leave your family alone, but you are scared that what happened to your other family members – like the stories of your own nan – will happen to you too. When she is finished speaking to you and your kids, the case worker leaves and tells you that you will hear from her soon.

It’s now upon her to determine whether your children are taken or not. This is what happens when the department begins to surveil your home, and this is still happening to low-income First Nations families in Australia today.

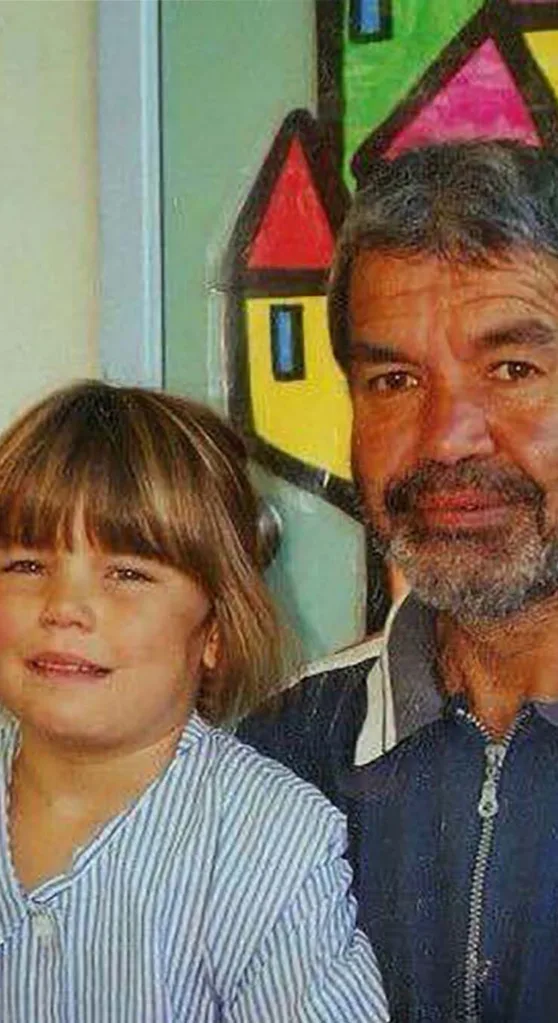

In this story, I am the daughter, and the father is my dad.

Living Under The Department’s Watch

The department intruded on my family without invitation from the moment I was born. And this intrusion persisted for years. In fact, 10 and a half years.

It involved unexpected visits and calculated surveillance, which ultimately led to my removal. Every observation and note taken was weaponised against my family, in court and beyond. The case workers assumed the role of professional storytellers, narrating tales that often went unchallenged and were accepted as truth in the legal process.

Even when I had very rare visits to see my family, it was under surveillance. I remember when a stranger arrived at my mum’s Elphinstone Road housing commission flat in Coogee. This stranger observed my family and every room, making notes on whether I “looked” safe in my own mother’s home. I came across the “assessment” when I was 25 years old. The notes were awful and discriminatory towards my parents and continued to argue that my best interests would be served by me remaining a ward of the state.

Case workers are entrusted with the responsibility of upholding the state’s child welfare laws. However, it is concerning that many of these individuals lack significant experience and are making crucial final decisions regarding whether to dismantle families, punish them due to their poverty, or provide support. These actions are mandated in NSW by the Children and Young Persons (Care and Protection) Act 1998 and through other legislation throughout the different states and territories in Australia.

As tools of the state, these case workers are tasked with investigating every report of child maltreatment, regardless of its source, through the state’s ROSH (risk of significant harm) reporting processes, despite the racism that often leads to these reports, or the racism in the bias, prediction and action to make “emergency” removals. These investigations often involve searching the family’s home, just like the search I have described. These individuals, who are essentially strangers, enter homes without clear, prior informed consent and hold the authority to disrupt the fundamental rights of family integrity.

They possess statutory power to either remove children based on their own authority or facilitate emergency removals or the implementation of court orders, resulting in children being taken away from their families and placed into foster care, residential facilities, hotels with strangers or, in horrific cases, prison. This can lead to the permanent severing of family relationships through the termination of parental rights, drastically altering the futures of children.

From the age of 10 and a half to 18 I had my childhood stolen from me – a significant period of time in a child’s life.

As I reflect on this time, it brings me immense pain. I am reminded of how the system deprived my family and community of crucial moments, those times when memories are made and stories are shared between parents, children and their community. All of that was taken away from me.

A Lasting Effect

In 2023, our communities united to protest against the forced closure of the National Centre of Indigenous Excellence, a significant place for many of our children that was already experiencing the effects of gentrification and isolation. Our advocacy efforts were consistent, with the entire community actively participating. However, amid this collective action, I had a distressing encounter. An Aboriginal case worker, who had taken me away years ago, recognised me. She played a big role in stealing me and harming my community. She approached me and my daughter and remarked, “That baby looks like Alby … Vanessa, you also resemble your father.”

I immediately identified her and felt a wave of sickness. When she attempted to embrace my baby, I firmly said, “Do not touch my child. I am not prepared to face you or be in this moment with you.” Unaware of the trauma and heartache she had caused, she seemed puzzled by my response.

I continued, “You took me away from my father, and he’s no longer here. You are not the hero in this story or a good person.” My partner, Ellia, sensing my distress, suggested we leave, and reassured me, “You are safe, bub.” I disclosed to him, “That woman took me.” The last memory I’d had of her was when she knocked on our door all those years ago and stole me.

It is concerning that the case worker thought she had the access and right to be in contact with me, to have a conversation, that she even felt in any way we were on any kind of terms, and – the most triggering and harmful thing – that she attempted to interact with my child.

This incident highlights that many case workers are unaware of the lasting harm caused by their actions. She probably thought she did the right thing, and that’s the problem. One reactive decision, instead of proactive, or one racist decision, to remove an Aboriginal child from their family, community and place, has worse long-term consequences.

When I reflect on this as an adult, I wonder how she sleeps at night, knowing that she ripped an Aboriginal child from her family.

How does one sleep knowing your job is to break families apart? Knowing that you are contributing to greater harm than love? Knowing that while a fast decision has been made, that there are serious long-term consequences to be had?

How does one sleep knowing that you have created more barriers for families? That you are about to drag a family, most likely a struggling family, through courts and systems, and subject them to more racism?

When Case Workers Define ‘Neglect’

Resources in the current child welfare system are often disproportionately allocated towards child removal and out-of-home care. Redirecting those funds to support community needs aims to address the urgent number of child neglect cases by shifting the system’s resources – and therefore its focus.

When it comes to department intervention, neglect is often given as the foundational reason for removal. This often keeps it ambiguous as to what the neglect actually is. Recognising that neglect is often the result of systemic issues – such as poverty, lack of affordable housing and limited access to healthcare – means that policies and interventions should prioritise providing families with the support they need to overcome these challenges.

This could involve offering financial assistance, housing support, quality healthcare, and mental health services and support. By investing in community liberation and emphasising prevention, we can work towards creating a more equitable and proactive approach.

If there is allocated funding for removal, it will be used for that. This results in the overemphasis on removals we tend to see. The same goes for incarceration. If there are new prisons built, the beds will be filled.

The focus on child removal and putting children and young people into out-of-home care places significant strain on families and perpetuates a cycle of trauma. The current system often fails to address the root causes of neglect, resulting in high caseloads for social workers and limited resources for preventative measures. If we allocate those funds directly to the needs of the community, shifting our focus away from removal and punitive responses, we will begin to see changes. Redirecting funds towards prevention and early intervention initiatives allows for a proactive approach in addressing child neglect.

If governments invest in community-based programs that provide education, parenting support, mental health services and access to basic necessities, families can receive the necessary tools to prevent “neglectful” situations as identified by the state. In other words, anything that can be provided to support the family and not result in a removal, so their definition of neglect cannot be used against the family.

Shifting resources from child removal and out-of-home care to community liberation presents an opportunity to meet urgent community needs. It is an investment in the wellbeing, stability and liberation of families, leading to better outcomes for children and our communities.

How Can The Court System Truly Support Child Welfare?

The court system plays a crucial role in the out-of-home care sector, serving as the ultimate arbiter in determining the fate of children and families involved in child welfare proceedings. Judges and courts must be educated and culturally aware, understanding the impacts and biases at play between the state and the family. By promoting fairness, equity and cultural sensitivity in decision-making, the court system can contribute to positive outcomes for families and promote the preservation of cultural connections. I am seeing a change in how the rights of children and young people are met in the courtroom, but we have a long way to go.

The primary goal of the court system should be the preservation of families whenever possible, ensuring that the removal of children from their homes is a last resort. Judges should be committed to understanding the dynamics of family systems, recognise the impact of separation on children and actively seek alternatives to out-of-home care.

The state simply cannot be a parent. The state knows no love. It will never nourish the beings of the little people, especially when its roots begin in the history of a nation built on stealing kids.

This is an edited extract from Long Yarn Short by Vanessa Turnbull-Roberts (UQP, $34.99), out now.

This article originally appeared on Marie Claire Australia and is republished here with permission.