When Thomas Barnes was 23, he was convicted on low-level drug charges. He never went to prison, but for years he was serving a life sentence anyway – one that affected nearly every aspect of his experience – because he had a felony on his record.

In 2003, police broke into the house where he was staying in the Detroit area. There, they discovered small quantities of marijuana. The drugs weren’t his, but he wouldn’t offer up those close to him to the police.

“I was unwilling to testify against friends and family,” he said.

He was offered a plea deal that would keep him out of prison in favour of probation, but leave a felony on his record.

“I was grateful that I wasn’t in prison, but still confused as to the ramifications of what this felony charge meant. I had no idea,” Mr Barnes, now 42, told The Independent. “I was still a kid. I was still living at home with my parents. I didn’t know what this meant.”

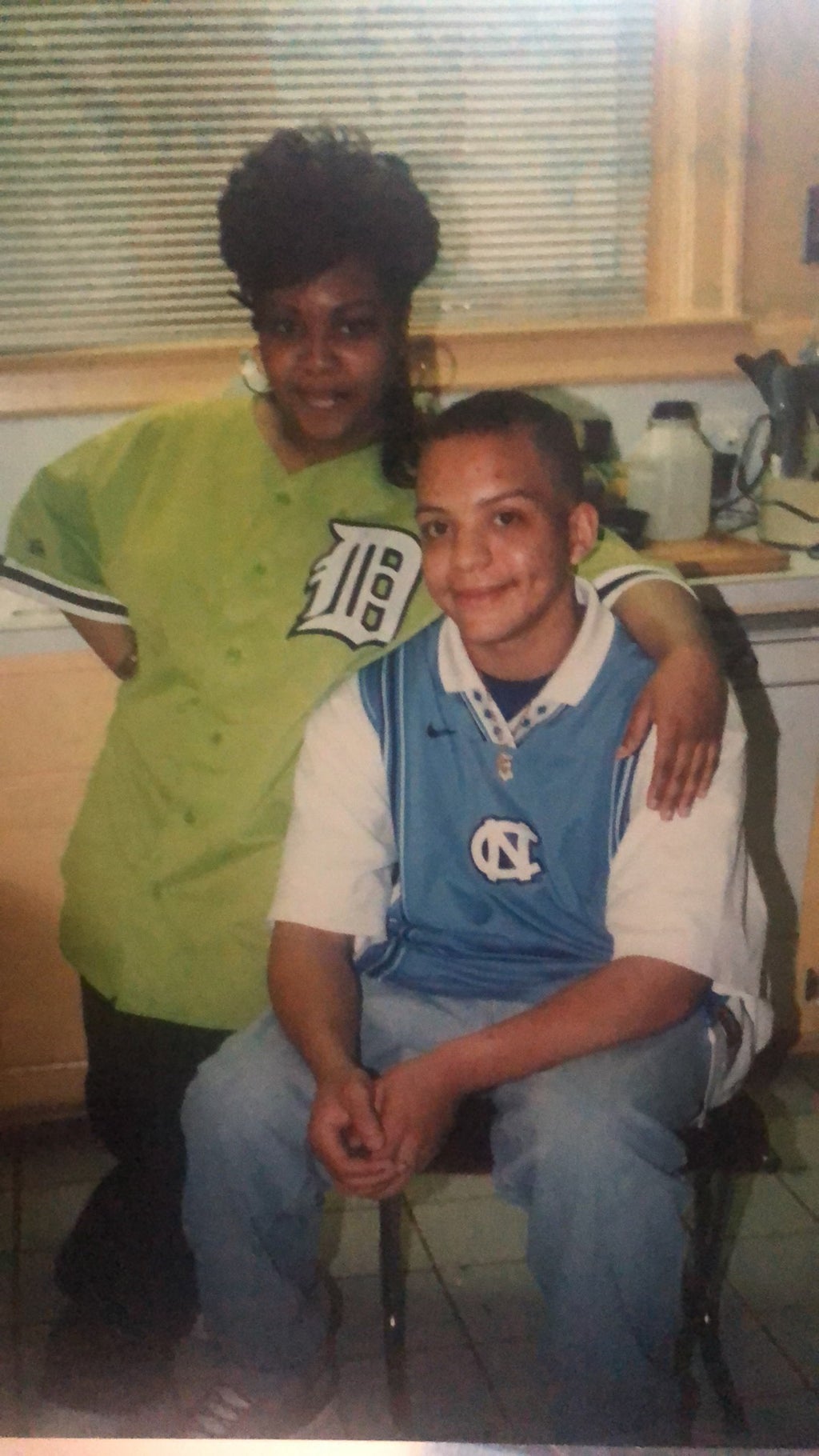

After successfully completing his sentence, Mr Barnes went on to work in youth mentoring in the city of Mt Clemens, Michigan, helping kids avoid getting into the trouble he found himself in, but his record remained a barrier.

Even though he worked with kids every day, he often was barred from working inside schools – or even going on field trips – because of his convictions.

“As I’m trying to go on field trips for my kids’ school, you have to fill out a background check. You have to check the box if you’ve been convicted of a felony or not,” he said.

“We can’t get an apartment because we’re being discriminated against because of my felony charge. The obvious one is, I work with some kids in some dangerous neighbourhoods. Everyone has a gun and is carrying a gun except for me, the felon. If I carry a gun it’s another felony. All of these things are happening. It’s like man, I wish I could get this expunged.”

Nearly two decades after his conviction, and after years of trying to better himself and the community around him, he would get his chance for legal redemption.

In 2020, Michigan became the third state in the country to adopt a so-called “clean slate” law, which uses technology to automatically expunge criminal records after a certain period for a wide-range of non-violent crimes. It was the first state to include felonies on that list, and to keep the process open for those with unpaid legal debts.

“I said, here’s my opportunity. Here’s my open door to have these felonies expunged off of my record,” said Mr Barnes, who had his convictions expunged in 2020 through an expanded court process under the law. (Full automatic expungements begin in 2023.) “It’s been pretty amazing.”

Some 78 million people, or roughly a third of the working-age US population, have some kind of criminal record, with disproportionate numbers in communities of colour. Even in states that allow people to clear their records after a certain period of time, the process is often slow, confusing, and expensive, resulting in far fewer expungements than convictions each year.

However, a growing movement of justice advocates, businesses, and bipartisan allies are pushing to make clean slate policies the norm. There are millions of Americans who have finished doing their time and are ready to start over, they argue. But a confusing, and often punitive world, of policies, assumptions, and barriers stand in the way of them doing that. A massive corrective, they suggest, is needed to put things back into balance.

“It hits everybody. It’s very close to home,” said Sheena Meade, executive director of the Clean Slate Initiative, a national advocacy group. “It’s not just a criminal justice issue. It’s definitely a workforce issue. It’s an American issue where we can bring people together and say people should have an opportunity to move forward, have a second chance, and live a decent life, and have access to stable housing, employment.”

It would be difficult to overstate just how many things having a criminal record makes extremely difficult, Ms Meade says, regardless of the often nuanced circumstances of any given crime. Nine in 10 employers, four in five landlords, and three in five colleges use criminal background checks to screen applicants. By some estimates, there are nearly 5,000 laws on the books which bar people with past convictions from most of the necessities of life: housing, work, access to government services.

Mr Barnes, the youth mentor, brought up the example of a man he was recently talking with, who had his record expunged in early February. The individual had been charged with a marijuana offense 17 years ago. Since the man’s conviction, Michigan has subsequently legalised recreational cannabis, turning it into a multi-million dollar legitimate business. Still, until clean slate came along, the conviction kept the man from living in public housing, as well as in a home his parents bought for him in a private development, where the homeowners association barred drug convictions.

“He was effectively homeless because of a marijuana charge from 17 years ago,” Mr Barnes said. “This man’s life was still in shambles until this morning because of these unfair, unjust laws.”

The stigma around past convictions can also have intense emotional and economic consequences for people who were formerly incarcerated.

In 2017, Candace Perkins’ job at the Michigan Secretary of State’s office was thrown into jeopardy when her decades-old convictions for petty retail crimes were discovered. She wasn’t fired, but was told she would have to move away from her family and mother in hospice in Grand Rapids to the city of Lansing to take a different, lower-paying position.

“It made my life a little, whoo, I saw a therapist because of this. I just couldn’t believe after all these years, I couldn’t work there,” Ms Perkins, 53, said. “The embarrassment of the management, I’m their friend. It was just a bad time when that happened for me.”

“It’s a burden off me,” she said. “I got a fresh start. Even though I’m a little older, if I want to relocate and do something, I can just start fresh. I won’t be worried.”

Many states without clean slate do offer processes for people to expunge their records after a certain period of time, but numerous factors keep those programmes from making any kind of massive impact.

Fees, such as Louisiana’s $550 filing cost, keep those already struggling to find work from clearing their record. In Ms Perkins’s case, before clean slate in Michigan, she was ineligible for expungement because she had more than one felony. In many cases, convictions are so old courts can’t even locate the records in question, so they can’t clear them.

In Utah, prior to the state unanimously passing a clean slate law in 2019, the expungement process often required hiring a lawyer and could cost up to $3,000, money that people shut out of large parts of the economy just don’t have.

“It makes it really easy to give up,” said Noella Sudbury, director of Clean Slate Utah, a group which helped spearhead the campaign for the clean slate bill.

She remembers putting on an expungement clinic in 2017. Individuals from around the state drove for hours to attend, and there was a line around the block.

“I began thinking, ‘Well, this isn’t feasible. We will never be able to put on enough clinics. It literally wasn’t possible.”

In Michigan, prior to clean slate, courts were convicting about a quarter million people a year, but only expunging the records of about 3,000 people in that same time period.

And as with much else, the pandemic made things even worse, slowing or entirely shutting down courts, and delaying clean slate laws and other expungement processes all the same.

Despite these challenges, in the five states with full clean slate policies, there have been massive impacts. In Pennsylvania, the first state in the nation to pass automated record clearing, in 2018, more than 1 million citizens had their records sealed during the programme’s first year in operation.

The success of the policies in these states has inspired others to take up clean slate for consideration, with state’s like North Carolina, Louisiana, Colorado, and Missouri currently examining the policy. Last April, a bipartisan group of legislators introduced the Clean Slate Act in Congress, which would automatically clear the records of those convicted of certain non-violent, low-level drug offences.

Beyond just criminal justice advocates, the policies have attracted support from many businesses, including companies like JP Morgan, as well as faith communities.

“The Chamber of Commerce and the employers in Utah were a huge support to our campaign. They said, ‘We need these people in the workforce,’” she said, adding, “In Utah, we have a really strong faith community, having the headquarters of the [Mormon] church here. There is this idea that people can change, they can repent, they can be forgiven, and that second chances is something that we as a state support.”

Research shows that those who obtain expungement are extremely unlikely to commit a crime again, and, relatedly, within the first year afterwards, see a 23 per cent increase in income and 11 per cent increase in employment. It’s a population in dire need of work, at a time when the so-called “Great Resignation” is taxing employers looking for eager candidates.

“With that evidence in hand, we were able to go both businesses and it lawmakers and say, ‘Look, this is a win-win. It’s going to expand the talent pool to businesses, expand the tax base, improve incomes’,” said John Cooper, executive director of the advocacy group Safe and Just Michigan, which advocated for clean slate in the state.

“Safe communities are good for business. That narrative largely prevailed within the legislature and within the business community. We haven’t really gotten significant on pushback from the laws thus far.”

Justice advocates say they’re hearted to see states like New York and Delaware seriously consider clean slate, but that more is needed to truly reform the system, from strengthening clean slate bills to include more categories of offensives and automatic notification requirements to deeper structural changes to the economy and criminal justice system.

“The criminal justice system preys on poor people. Poor people are put in bad situations and have to make bad decisions,” said Mr Barnes, the youth mentor. “In America, there’s a lot more that needs to be done, especially for kids coming out of Covid, who lost everything, and weren’t given anything in return.”

For the millions of Americans who had already lost most of their lives to that prison system, clean slate could offer them a way back.

Sheena Meade of the Clean Slate Initiative will speak at the upcoming American Workforce and Justice Summit 2022 , a two-day gathering of more than 150 business leaders, policy experts and campaign organizations focused on how corporations can meaningfully engage in justice issues and create change in the workplace and beyond. AWJ 2022, a project of the Responsible Business Initiative for Justice, will take place in Atlanta, Georgia, on 4 and 5 May. The Independent will be reporting from AWJ 2022 as media partner.