In 1998, Devin Townsend released Infinity, his first album under his own name. The record refined his immense yet melodic prog and became one of his most celebrated releases. It also pulled the polymath back from a crisis of ego that had put him in hospital. Three decades on, Townsend gives Prog a list of what he learned during that tumultuous time.

There’s a rare moment of pause from Devin Townsend. “Please try not to make this sensationalistic,” the progressive metal maverick asks. “What I’m trying to do with expressing this is to help people who are going through something similar. If this comes across as, ‘I did this many drugs, I was a fucking crazy person and they put me in a mental institution,’ that’s really going to do a disservice to this.”

You can understand Townsend’s apprehension. He and Prog are talking about his 1998 solo album Infinity, which has been remastered and re-released for its 25th anniversary. And, as the multi-instrumentalist just summarised, the story behind the record is a sensitive one.

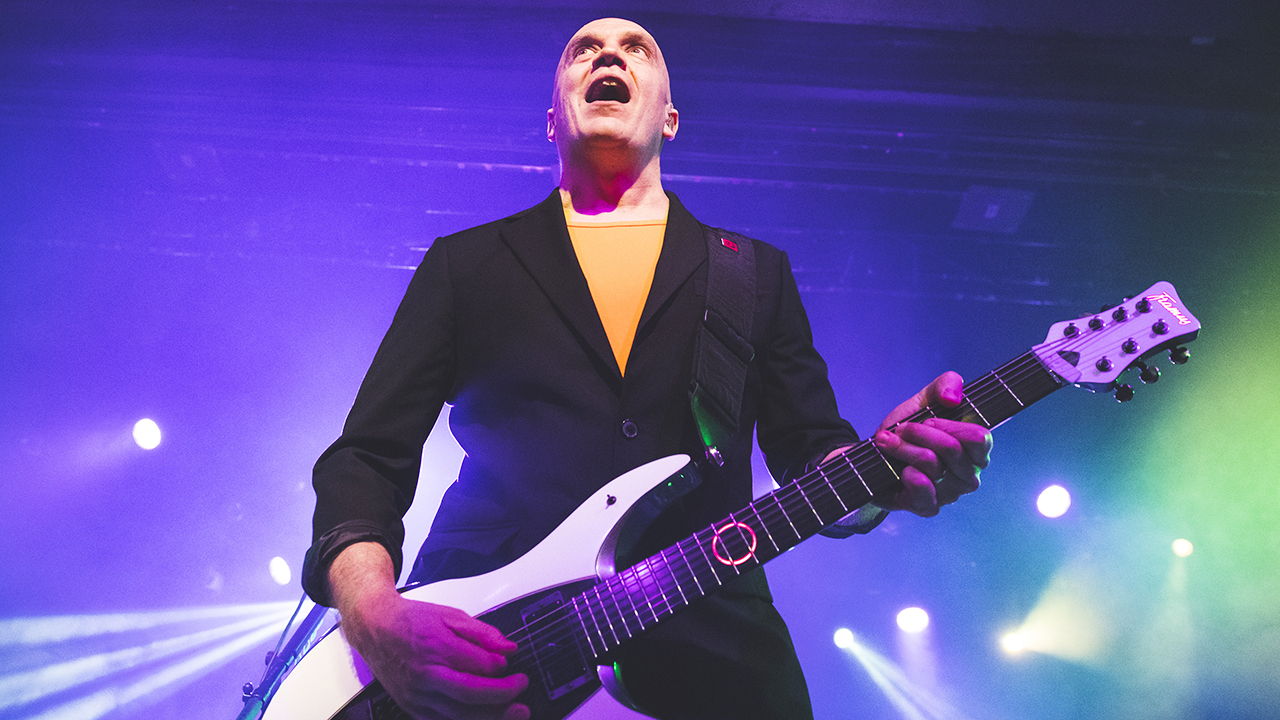

Knowing Townsend’s work is almost a prerequisite for being a progressive metal fan in the 21st century. The Canadian polymath entered the public consciousness in 1993, singing for Steve Vai on the virtuoso’s Sex & Religion album. For most artists, that venture (whenTownsend was barely in his 20s) would have been an unassailable career highlight. However, Townsend’s influence and myriad projects since have turned it into more of a footnote.

The musician earned prominence on his own terms with the extreme metal outlet Strapping Young Lad in the mid-90s, then began contrasting the band’s roaring and riffing with the immense yet melodic textures of his solo music. Since Strapping Young Lad were dissolved in 2007, he has dedicated himself to the Devin Townsend Project (an extension of his solo career from 2009 to 2017), country one-off Casualties Of Cool (2014) and a pair of pandemic-era ambient records. His discography is currently 26 studio albums long, and for most entries you’ll find loyalists declaring it his greatest and/or most impactful work.

Townsend, however, downplays his legacy with typical Canadian humility. “None of my albums are important,” he flatly says. “Not even one of them. I think the thing that’s important is the journey.” There’s an exception to that blanket statement, however: “As a roadmap, and as a flag on that journey, Infinity was important.”

When it came out in 1998, the album was the first to bear Townsend’s real name (his two prior solo records, Cooked On Phonics and Biomech, were released under the pseudonyms Punky Brüster and Ocean Machine respectively). It became his first music post-Vai to chart when it reached No.29 in Japan, and it pushed his progressive potential, previously only heard on Biomech, to greater levels.

Infinity’s opener, Truth, both reintroduced and ramped up Townsend’s now-distinct wall-of-sound production. Dense layers of guitars, keyboards and multitracked vocals explode from both the song and the rest of the album, to the point that Townsend later interrupts War to cry, ‘Just stop the noise for once, please!’ Elsewhere, Christeen and Bad Devil still represent some of the musician’s most listenable material, casting memorable choruses against Broadway-scale symphonics and saxophone solos. Biomech may have built the mould for the sound of Townsend’s solo work, but it was Infinity that set the standard every follow-up had to reach.

This isn’t the kind of importance Townsend is talking about, though. In the lead-up to the album, the then-25-year-old developed what he today describes as “martyr syndrome” – the condition led to a greatly inflated sense of self-importance and then, for a brief period, time in a mental health hospital. It wasn’t until Infinity was finished that he gained a more grounded perspective on the world. Although his drinking and drug use at the time compounded the problem, he’s eager to point out it was not the root cause.

When I joined Steve Vai’s band it was with a type of turbo naïvety… I realised this thing I held so sacred was nothing more than a commodity

“Infinity was the first solo album that I had done,” he explains. “Biomech was more of a conglomeration of demos and things from a period prior; but with Infinity, I produced it, I engineered it, I mixed it – and I wasn’t familiar with that process. As a result of that, I thought that album was so important, so significant, that I was on a mission. Because I was self-deprecating and insecure and arrogant, I interpreted that mission that I was on as being like, ‘You’re doing God’s work!’”

Townsend traces what caused that way of thinking all the way back to when he was young. The future prog idol was born on May 5, 1972, to a nursery teacher mum and a steel worker dad. Raised in what he describes as “the boonies,” he was an isolated child, and he grew up unsure of how to express his feelings in a healthy way.

“My grandparents were from the UK; my grandfather from Ireland,” Townsend remembers, “so there was this kind of ‘stiff upper lip’ thing. Certain overt displays of emotion were uncouth. As someone who was very sensitive, I think I was like, ‘How do I express this?’ Music was something where you could be as emotive as you want to be, and it was accepted by family and by society. It was like a loophole, and music became more than a product for me.”

Townsend started writing songs as a young man, with that early start being met with early attention. After he started sending some of his music (then made under the pseudonym Noisescapes) to record labels, he got signed to Relativity – the home of Vai. When the virtuoso needed a vocalist for Sex & Religion, it didn’t take long for Townsend’s name to enter the conversation, nor for the Canadian to get the job.

He was 19 when he started living every teenager’s rock’n’roll dreams, thrust from the wilderness of the Great White North to performances on The Tonight Show and arena tours with Aerosmith. However, in that commercialised world he grew more and more furious, seeing how cynically bigwigs treated the medium that gave him emotional catharsis.

“When I moved to Los Angeles and joined Steve Vai’s band, it was with a type of turbo naïvety,” Townsend explains. “I became so angry when I realised that this thing I held so sacred was nothing more than this commodity. From that point, I was like, ‘I want to use whatever musical talent I have just to make things explode.’ Then, Strapping!”

I was paranoid and told my best friends they were only in my life because they wanted something

Strapping Young Lad’s 1995 debut, Heavy As A Really Heavy Thing, saw Townsend channel his frustrations through music, the one coping mechanism he’d ever known. It didn’t work. During the making of second album City, released in 1997, he was still enraged, but was also using psychedelic drugs. Within the next year, by Infinity, “all of my experiences had time to gestate into an identity.” Townsend – confused, angry, on substances and unsure how to handle the ways he was feeling – began to view himself as the classic media trope of the tortured genius artist ahead of his time.

“I ended up going down this avenue of thinking that I knew it all,” he remembers, “and that it was my responsibility to tell everybody in my life what they were doing wrong. If I was smarter, it could have ended up doing something like trying to start a cult. But fortunately I’m a dumbass, so everybody was like, ‘Oh, fuck you, man!’”

Townsend also grew cynical himself – not with music, but with human beings. He began to believe the people in his life weren’t truly interested in him. “Best friends of mine that were around for years, I was paranoid and told them they were only in my life because they wanted something,” he says. “It was just all the stereotypical, paranoid, delusional behaviour that comes with a combination of somebody whose identity had been established [in the public eye] prior and then, all of a sudden, drugs. A lot of this type of behaviour is documented now with those kinds of psychedelic experiences.”

Eventually, friends and family called him out for how he was acting, and he was checked into a mental health hospital. It was there he realised the clichéd role he was playing – and the extent to which he’d been “getting off on it.” He recalls: “I was like, ‘Oh, shit’, because I was in this facility with a bunch of people who are chronically schizophrenic and really, severely troubled. I remember thinking, ‘Wow, how much of this is me playing an artist?’”

The importance I’d put on this thing was pulled away by me going, ‘Dev, this is one record out of dozens of records’

After being discharged, he worked on Infinity; and many of the album’s lyrics ask how one can forgive oneself for one’s own unjust behaviour. He performed lead vocals, guitars, bass and keyboards almost entirely by himself, and also acted as producer. Once everything was finished and he got to listen back to what he’d just made, he had his reality-restoring revelation.

“I remember listening and going, ‘Oh, it doesn’t sound that great!’” he laughs, that humility returning. “The importance I’d put on this thing as being a world-shifting piece of art was pulled away by me going, ‘Dev, this is one record out of dozens of records.’ I listened to ABBA and Infinity side-by-side and it was so clear to me.” Then why release it? “Because I couldn’t have done any better.”

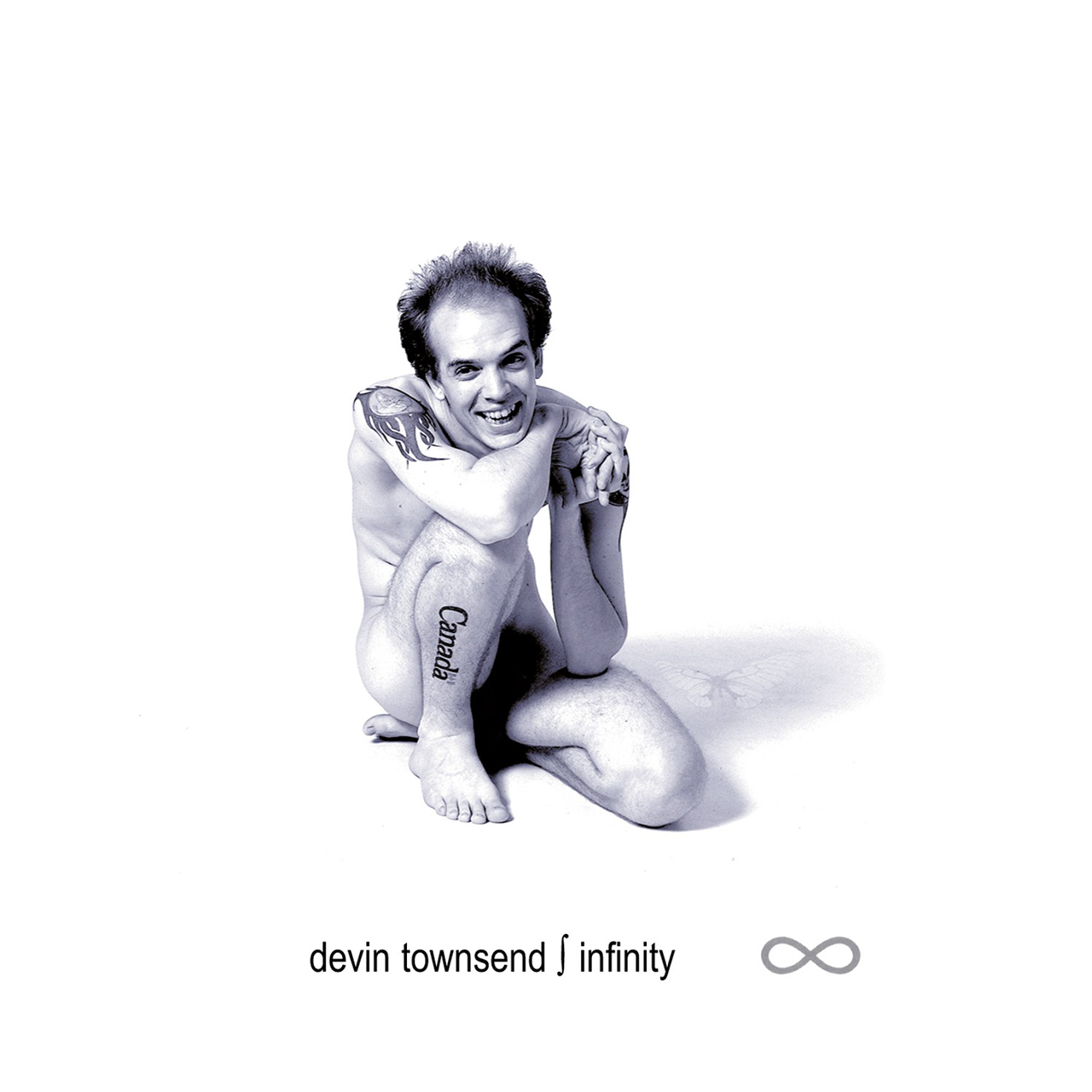

The sharp learning curve he went through, he says, makes Infinty worth reissuing 25 years on. However, with that idea came another from his record label: he should recreate the album cover in 2023. The original artwork depicted him naked when he was in mid-20s. He’s 51 now.

“When I did it, I was 26 years old and not eating,” Townsend reflects with a laugh. “It was part of this ‘mission.’ I called up my friend, this poor lady, and I was like, ‘I have to do this.’ So she had to spend a day Photoshopping my dick out of photos. Conversely, this time, when they were like, ‘Would you consider doing it again?’ I was like, ‘Fuck sake!’”

By posing naked in middle age, though, Townsend learnt something. “I realised I’m not ashamed of the things I did back then,” he says. “I have to honour who I was, because I wasn’t trying to be an awful person. I was doing my best with what I had at that time.

“It’s not that the things I was saying were fundamentally wrong,” Townsend concluded, “I just got how to behave wrong. Because it was such a humbling experience, Infinity stands alone in my catalogue as something of such magnitude.”