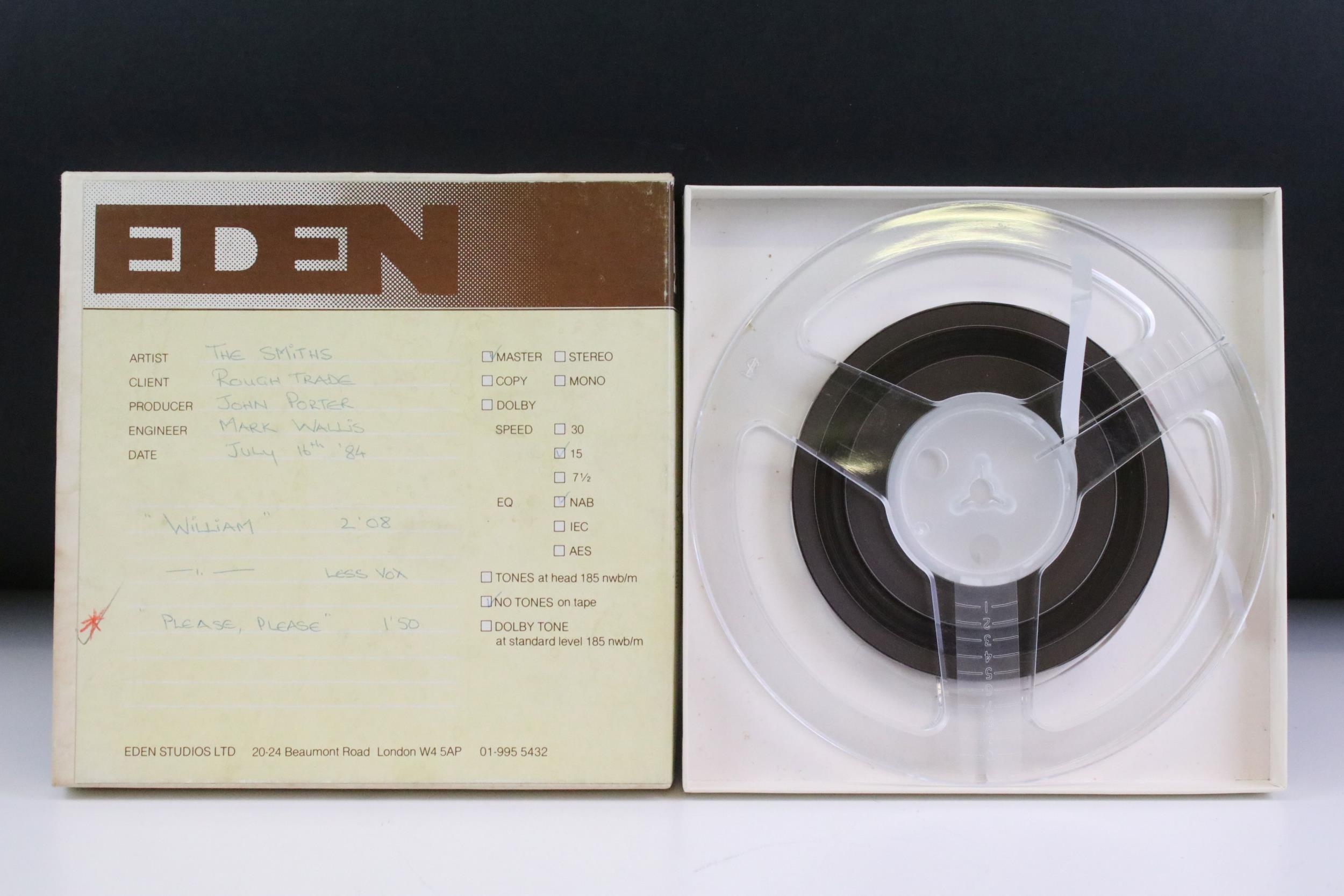

They’re hailed as one of music’s most influential bands, but as The Smiths’ debut album’s producer John Porter tells us, they were more than a little green during those early studio sessions. Porter spoke to us to mark the auctioning of a huge array of original test pressings, acetates and original mixes which were discovered - unplayed since the 1980s - in his sister’s attic.

The auction is being put on by Wessex Auction Rooms on Friday 24th January. The team’s vinyl specialist, Martin Hughes, had this to say about the amazing assortment of 53 records, collector's items and first pressings up for bidding; “Spending time with John Porter has been such a fascinating experience. I am fortunate to deal with important collections of vinyl records every day, but those collections rarely come from the person who produced them. The auction catalogue has been online for a week and has attracted interest from some of the biggest collectors of The Smiths, vinyl records, and music memorabilia in the world. I am expecting some fierce bidding!”

John’s journey into record production stemmed from a deep love of R&B and the blues This evolved into a passion for recording - alongside a firm creative relationship with Roxy Music’s lynchpin, Bryan Ferry (more on that in the interview).

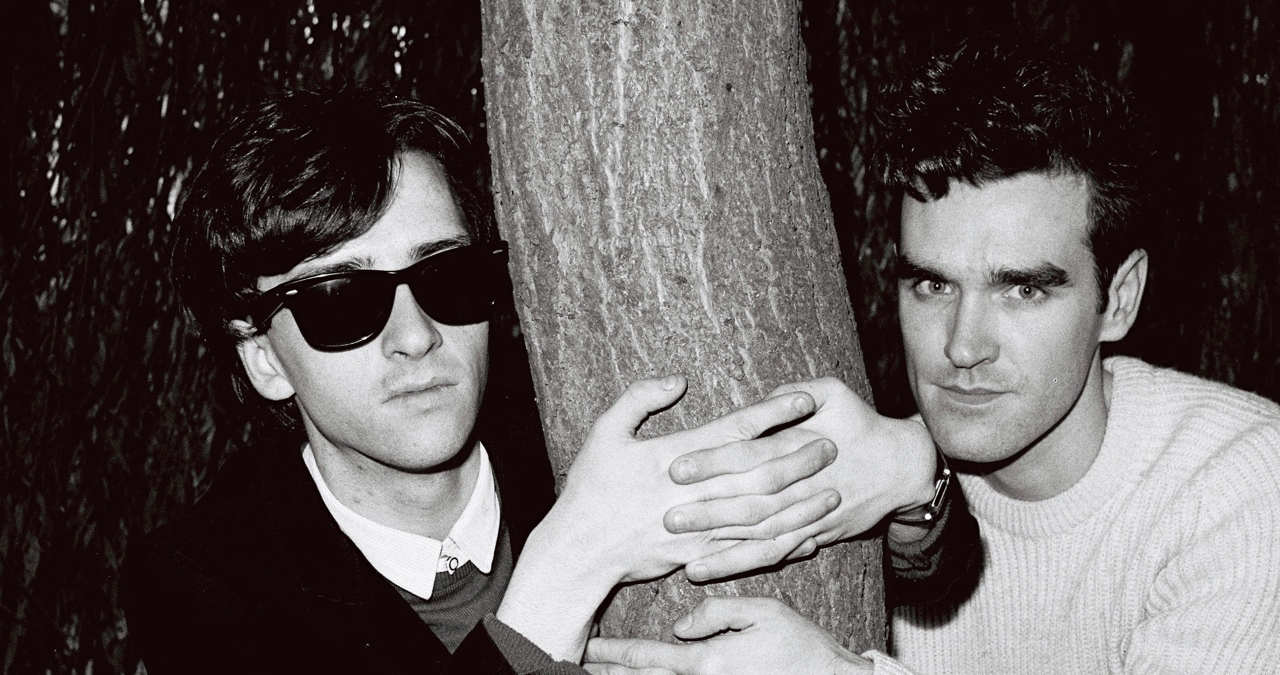

After a varied career, Porter met The Smiths whilst working on a BBC session. Impressed with his studio aptitude and dissatisfied with an early recording of their debut produced by The Teardrop Explodes’ Troy Tate, Porter was enlisted to take the production reins, re-record and re-produce the entire thing and eventually helm some of the biggest cuts of the band’s career.

Since then, John has, in his words, worked on close to 500 records, and after 30+ years in the US (between LA and New Orleans) collaborating with a range of blues, jazz and rock musicians, has returned to the UK.

We were intrigued to find out more about his life and career, but first, we wanted to know more about the upcoming auction.

MusicRadar: Thanks for speaking to us today, John. Firstly can you give us a bit of an overview of this upcoming auction, and what the items are that you’re putting up?

John Porter: “What’s strange is that I didn't know I had them. Sadly, my older sister died about six months ago and my younger sister was clearing out her house up in Leeds. She had somebody go into the attic to see what was up there. There were three bags of stuff up there. There were two bags of Marvel Comics that dated back to the 1960s. The other bag had, not all, but 95% of the stuff that's in the auction.

“I honestly don't know how it got there. I mean, obviously I must have left them there at some point.

“I used to live in Hampstead in London, and when I went to live in America, I left piles and piles of stuff in the attic of the house. I must have separated [the records up for auction] out and put them in the bag and took them up to Leeds.

“Over the 30 years I was in America, the house was rented out. As I say, I’d stashed lots of old records, tapes, cassettes and acetates up there. One of the tenants went up there and took everything so I’d assumed these [records] had been lost too.

“In those days, I used to mix a song and then I'd take a quarter-inch tape of the mix home to listen to the mix. If the mix was alright, I'd go to the mastering room - with the Smiths I usually mastered with Tim Young at CBS. I'd get an acetate or test pressing, or both. So, these are what's in the auction. They’ve probably been played only once - back when we were making those tracks.”

MR: That’s extraordinary. A large proportion of material comes from your time working with The Smiths (Porter helmed the band’s eponymous debut, and many of the singles that would launch them into the public consciousness). What do you recall about that era of your production career, and your working relationship with the band at that time?

JP: “Studios can be quite intimidating places. I wanted to make it comfortable for them. I remember my own first studio session at the old Pye Studios in Marble Arch and it was awful. I hated it. The producer wouldn't let me in the control room - he was just a disembodied voice through the headphones. Saying ‘do it again, do it again.’ There was no encouragement.

“My thing with a young band like The Smiths was to take them somewhere that wasn't intimidating, and make them feel comfortable. They responded to that.”

"They were very much a Manchester-based band and they didn't like leaving Manchester. (The band had recorded the first version of their debut at Elephant Studios in Wapping, London with Troy Tate). So, I decided to go up to Manchester and we re-recorded their debut at Pluto Studios

“I felt that when I first came to London, I'd been a clueless kid from the north, and I recognised - as far as making records was concerned - that they were also clueless kids from the north. But I had a few years on them and had been doing it longer. I did have a lot of input into the arrangements.

"They didn’t really know about recording. They didn’t know about overdubbing or about song structure or anything, Johnny would just play a riff which would go on for two and a half minutes, Morrissey would sing over it, and that was it. I tried to bring in some light and shade, because they didn't necessarily have verses and choruses as such in their songs, so I used to try and arrange the dynamics of the song. That's why we came across a sort of formula of having a guitar intro, a breakdown in the middle and a ‘re-intro’.

"We'd make the guitar lines play in a lower register below the vocal during the 'verse' and then break out into a higher register during the 'choruses', adding harmonics, backwards echo and doubled melodic hooks etc (all on the guitar).

"There were certain parts of the song I would try and build up more, so that there was more of a sense of tension and some release from it to make it more of a pleasant journey, rather than such a linear thing."

MR: Can you recall the production and making of This Charming Man?

JP: “With This Charming Man, the timing on the original track (that we recorded at Matrix Studios in London ) was hard to work with. I think I'd edited between a few takes to get one good take (which was not unusual), but you did that anyway in those days.

"I went back up to Manchester, and booked a day at Strawberry Studios. I’d recently got a LinnDrum and I copied Mike's drum parts from the track we'd done in London, and asked Johnny and Andy to play along with it. I overdubbed the drums last.

“My theory always was (and still is) if you can’t dance to it, it’s no good. So we recorded the song again - the track was a bit simpler, but the arrangement was the same. The London version had the same basic arrangement, but what we did in Manchester was a bit smoother and a bit cleaner.

"We used the LinnDrum as a click on all the subsequent tracks I did with the band I think, though maybe one or two didn't have a click.

MR: How about How Soon is Now? That was quite the sonic departure for the band, and still sounds quite unlike anything else in their songbook

JP: "It started in the studio. We had two days booked at Jam Studios in North London. We were there to do the William It Was Really Nothing single. We also cut Please Please Please, which I thought was one of the best things we'd ever done.

“So, that was our brief, to get those two done. We got them done pretty quickly and had time left over. The band didn’t really do demos, but usually they’d have a basic idea or a structure of whatever song they wanted to do, but with How Soon is Now? there were no pre-conceptions. I never heard a demo. [Johnny Marr recalls demo’ing the track, then dubbed ‘Swamp’ before the recording session, before building up the song into the tremolo-daubed monster it became with John, Ed]

“I programmed the LinnDrum (again!) congas, shakers and cowbell and tambourine. to get a groove thing going in the room. Those elements remained in the final mix.

“Johnny will probably dispute this but I remember sitting in the studio playing That’s All Right Mama on the guitar, saying to him ‘let’s do something like this, just stay on the one chord (F#) for a bit. ’I remember asking Johnny if he had any other licks, and he had this thing that was in a high register. It actually sounded a bit like William, but I asked him to play it two octaves down and slow it right down. That would become the B-section. So, they all started playing, along with the box and what you hear is , after an amount of tinkering, the eventual result.”

“A lot of the dynamic arrangement and sequencing was assembled in the mix, The band didn’t play it quite as it sounds. For the re-intro, I just switched out the drums and the bass and let the guitar play on its own.”

MR: So you were quite pivotal in that track coming to life. How did you feel about its eventual success?

JP: “I really wanted them to have success in America, but I didn't think that [what they were doing] was something the Americans would really pick up on. But, I thought that How Soon Is Now? could do it, and with it, they could break through in America. I was very excited about it. I remember calling Scott Piering who was doing US publicity for the band. He had a broader musical ear than most of the Rough Trade guys and he really dug it. He got it straight away.”

“Sadly, Geoff Travis didn’t like it, and I got fired shortly after.

“Geoff’s view was that I was having too much fun, and it didn’t sound like The Smiths. He put it on the B-side, then it came out as a 12’, and finally as a single. I’m not really sure how well it did in America, but when I lived there that’s the one I used to hear on the radio or on TV most frequently.

"I think I saw the writing on the wall when we did the Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now single, and Stephen Street engineered, I could see that Morrissey wanted to work with Steve."

MR: It sounds like you built up quite a close creative relationship with Johnny particularly, do you think your role was important in helping to shape The Smiths into the band they would become?

JP: “The Smiths would come in with songs, but in the early days they didn’t have many ideas when it came to arrangements. If I suggested something they liked, they would accept or adapt it.

"Johnny was a very quick learner. He'd have his part down, you know, and Mike and Andy were receptive, and they'd play their parts solidly.

"At that stage, Morrissey didn't seem to care too much. I think he relied on Johnny's musical judgement. We'd often overdub the vocals later when he'd come in with his book of lyrics [to do the vocal].

"Sometimes I’d do the track with the band , make a cassette of a rough monitor mix and drop it through [Morrissey’s] letterbox. The next day he’d come in and sing it.

“They'd obviously rehearsed some of the songs before recording them but some of them were pretty much put together in the studio. Johnny had been interested in the production process right from when we first started. I remember when we did the first track together. I laid out the mix, and explained what was happening on the faders. Johnny was immediately interested, whereas Morrissey’s eyes glazed over. Johnny was a very quick learner. He had great energy, and we had a lot of fun.

"I really enjoyed working with The Smiths, but Morrissey was always difficult. When I first met him, he was very polite and would send me postcards saying how much he'd enjoyed it, thanking me. This quickly changed to complete disdain. I don't think Morrissey liked me. I don't think he liked my friendship with Johnny.

“After Geoff fired me, Johnny wanted me to carry on doing stuff. So I came back and did a couple of other singles with them, but then they settled into working with Stephen full time.

“It was frustrating for me, in a sense. I mean, you know, you build up a relationship with a band. I figured we were just starting to really get somewhere.

MR: Many years before that, you first entered the music world via your close friendship with Bryan Ferry. You later joined Roxy Music for the album For Your Pleasure and ended up being a regular producer for the band and Ferry particularly. How did that relationship differ from the one you had with The Smiths?

JP: “Well, Bryan had a band called The Gas Board when we were at university. I joined them a couple of weeks after starting at the university, and so we were good pals.

“When Bryan said he was gonna start Roxy Music, he asked me if I wanted to join and play the guitar. I said that I didn't really want to do it. At that point I was sick of the whole ‘art school’ thing,

"I was totally into the blues and I didn’t want to do it but we stayed quite close. When I came back from America, I got a call from Bryan saying that Graham had left, and would I play the bass for them.

“So, I agreed to come in and do the recording (for the band's second album, For Your Pleasure), but I didn’t want to do the gigs. I didn't really see myself as a bass player - that was probably a mistake. I never joined Roxy Music. I could have joined when they formed, and had a second chance to join them as a bass player. I just wanted to go in a different musical direction.

“I probably shouldn't have been in such a hurry to go somewhere, should have just been a bit cooler and stuck around because we could have made some interesting music, but I still see Bryan and enjoy his company and I still record with him. I recorded with him a few weeks ago.”

MR: Are you still producing records now, John?

JP: “Yes! There's an album coming out in about a month. It’s a record I’ve done with Jon Cleary . We recorded it with the whole band live in Jon's house on Burgundy Street in New Orleans.

"Jon’s a great friend, he’s from Kent and has lived in New Orleans since he left school. We’ve made loads of records together. About seven or eight of Jon's albums and many others using Jon as a session player.

“I enjoy working with a team of session musicians who really know what they’re doing. It’s amazing that I can just say ‘how about we try that, or how about we substitute that chord for that’, or, ‘let’s make that a three-beat bar’ and they just do it. It takes little time to figure out what works and what doesn't work."

“In America, I was used to working with guys who could record a really good album in two or three days without needing to do any rehearsals.. that's a real rush, the most important thing is to use guys that share similar musical sensibilities and have really good communication."

“So yes, I still talk about The Smiths, and the stuff I did 40 years ago, but I’ve probably worked on somewhere in the region of 400-500 albums. Every day you’re in the studio is slightly different, and every day is great. I’m very much into what I’m doing at the time.”