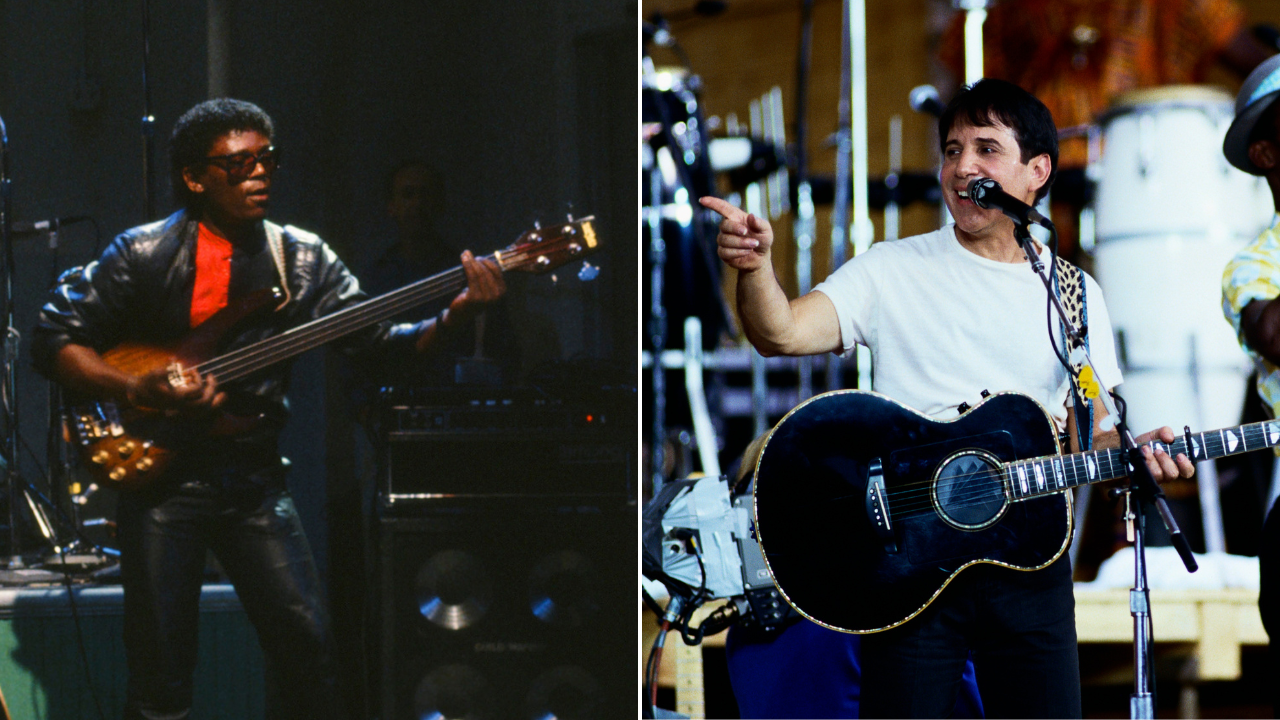

By now, many bassists know that Paul Simon’s Graceland album has earned time-capsule status as one of the highpoints in the recorded history of the fretless bass guitar.

Bakithi Kumalo put the instrument's trademark buzz in the ears of millions globally with his singular melodic and rhythmic step-outs on hits like Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes, You Can Call Me Al, and Graceland.

Kumalo’s bassline on The Boy In The Bubble showcases the instrument's unique sonority with particular clarity. As noted engineer Roy Halee remarked in Sound On Sound magazine, “Oh, man – that bassline is off-the-wall great.”

The 1985 studio session took place at Ovation Studios in downtown Johannesburg, with the cream of local musicians gathered in one room. Key to the track were accordionist Forere Motloheloa, who received a co-writing credit, Kumalo’s cousin Vusi Khumalo on drums, and guitarist Ray Phiri.

The song starts with Motloheloa's floating accordion figure, grounded first by Vusi Khumalo's backbeats and then the full groove featuring Bakithi Kumalo’s swung, bouncing octaves. “The feel doesn't have a name,” Kumalo told Bass Player. “But it's based on a Sutu shuffle traditionally played on an empty oil can with a tire tube and bottle caps on top.”

The first chorus begins with what essentially becomes the song's standout moment for the bass: Not a swooping upper-register lick or a blinding diatonic fill, just six consecutive, legato G's, rendered with an ear-grabbing, singing quality. Even more impressive is how Kumalo never phrases them the same way twice. Listen for his subtle variations throughout the track.

“My part really came from listening to Forere's left hand, playing and feeding off that. The reedy sound of his accordion blended beautifully with the growl of the fretless, and I think that caught Paul's ears, as well. He had heard recordings that Forere and I played on over the years.

“Every time the chorus came around, I treated it like it was new section and attempted to play those notes a little differently than the last time. At first, I tried the G's on the 10th fret of the A string, but they were a little too fat-sounding; on the thinner D string they had the perfect vocal quality.

“I used my left index finger to play them, and I always slid into and off of the first and last G's to match the delayed sound that occurs when Forere opens and closes his accordion.”

A final verse leads to a long out chorus. Kumalo stays the course, determined not to burst the groove, as it becomes apparent that his shortened notes are as important as his long tones. “I focused on being consistent with the part, but being especially aware to use dynamics when Paul was singing.”

From Kumalo's perspective, fretless bass is all about tone first. “The first step, before you play a lot of fancy licks, is to get the right sound one note and one string at a time. It shouldn't be bottom-heavy; it needs to have a presence in the midrange, like a trombone or a cello, so it can cut through.”

The other key, regarding tone and intonation, is his ears. “I don't look at the fingerboard, I listen to it. All of my fretless basses have no fret lines. I can't play on a lined fingerboard because it adds the extra step of having to look at where your finger is in relation to the fret line; let the blind man drive the car!”

To sum up, Kumalo advised, “Try to lay back a bit; the groove is pushed, but the bass needs to sit in the pocket. Also, listen to the melody and the lyrics. At the time my English wasn't too good, but I tried to understand the story and support the lyrics. Listening back now. I guess I was able to grasp it well enough!

“Practice getting your octaves and 5ths in tune so when you add other notes you'll have a good foundation to build on. Overall, I try to think like an upright bassist. Their whole approach is on developing a sound, and that's a good concept to bring to the fretless.”