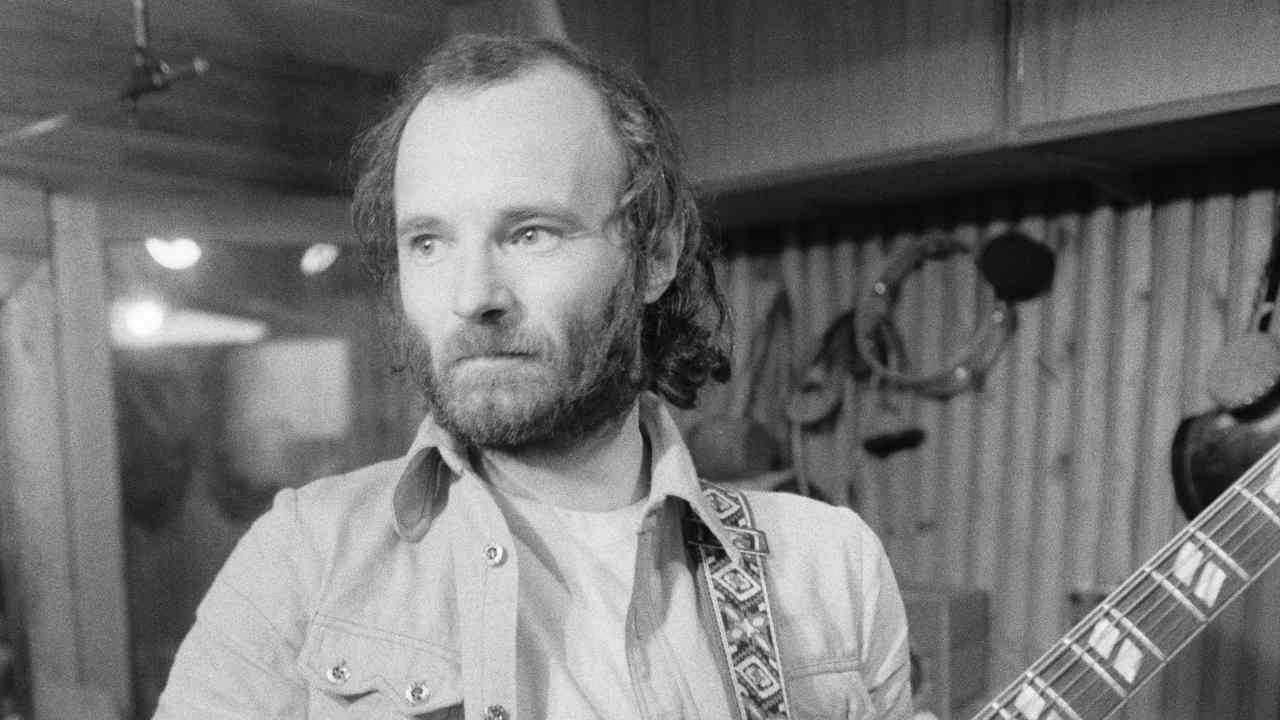

Michael Chapman never got the recognition he deserved. Starting in the late 60s, the British guitarist and vocalist released a string of albums that were feted by the likes of David Bowie, Elton John and, later, Sonic Youth guitarist Thurston Moore, but the public at large never caught on to his brilliance and he remained a cult figure until his death in 2021. In 2013, Chapman spoke to Classic Rock about the highs and lows of his career – and why he never got the breakthrough he should have.

So what do you do? Your manager’s packed up and gone. Your bandmate’s left with a woman in a green Mustang. Audiences, if they show up at all, are indifferent at best, sometimes downright hostile. You’ve been mugged. Your visa didn’t come through. You’re alone in New York, 3,000 miles from your loved ones. And you’re penniless. So what do you do?

You head home, of course. “That was the tour from hell,” recalls singer-songwriter Michael Chapman. “The only bit that went right was that I didn’t get shot. Basically the record company just wasn’t looking after me. They’d forgotten to get me a work permit, which meant that the clubs I played in had to pay them first. So I was running around America without a bean. I still have the bill from the Chelsea Hotel in New York.”

It was August 1971. Chapman, one of Britain’s most singular guitar talents, had set out on his first tour of the US to promote new album Wrecked Again. Bankrolled by EMI/Capitol and joined by bassist Rick Kemp, later of Steeleye Span, the idea was to begin on the East Coast and gradually wind westwards to LA, at that time the cradle of the hippie troubadour boom.

But Chapman never made it that far. Sharing a bill with one of his heroes, jazz great Cannonball Adderley, was the only cause for celebration. “We started off in Washington DC, which is America’s blackest city, and they hated us. Then we went to Philadelphia, to a kind of Ivy League jazz club for a week, and they hated us too. Then I got back to New York and played The Gaslight and nobody came. So I just got stoned all the time. Rick had domestic problems, so had gone home already. And my manager had bailed out long before that. So I was on my own, pot-less. I ended up on the next plane back. When I got home I said to my missus: ‘If that’s the big time, I don’t need it. I’ve retired. I’ll go sweep the roads or something.’”

The whole episode was also a sorry reflection of Chapman’s relationship with UK label Harvest. Wrecked Again was his fourth LP in three years for EMI’s progressive arm. It had once seemed like an ideal home for the 30-year-old Yorkshireman, whose improvised guitar sorcery came served with vivid lyrics and an intense stage persona. Perhaps the nearest parallel was labelmate Roy Harper, who occupied a similarly indistinct realm between folk and rock.

Fully Qualified Survivor, issued a year earlier, had been a defining moment in Chapman’s career thus far. A thrilling mix of avant-blues, descriptive acoustic picking, jazzy cadences and heavy-heavy riffs, the album featured a pre-Spiders Mick Ronson on lead guitar. Bittersweet beauties like Postcards Of Scarborough and Kodak Ghosts were offset with the blistering Soulful Lady and orchestrated 10-minute odyssey The Aviator. John Peel declared the album, which stopped just shy of the UK Top 40, his favourite of the year, calling its creator “one of the most interesting and inventive guitarists around”. Chapman seemed on the verge of big things.

By 1971 though, Harvest were rapidly losing faith. Sales of Window, the follow-up to Fully Qualified Survivor, were disappointing. And while Wrecked Again was clearly another minor classic – with Memphis horns, ravishing guitar figures and arranger Paul Buckmaster bringing in the London Symphony Orchestra – the label had all but given up on Chapman. “I asked them what they were doing for promotion and they said they weren’t,” he laments. “Then they said they’d put some money behind it if I played support on a really big tour. So I got the Emerson, Lake & Palmer tour, when there wasn’t a bigger one in the world. But they still didn’t do it. I was really pissed off with them, because an awful lot of work went into that album.”

It was to be Chapman’s last record for the label. “All the oddbods, all the losers, were signed to Harvest: me and Roy Harper, Principal Edwards Magic Theatre, Syd Barrett and Kevin Ayers. We were a bunch of stoners. EMI didn’t have a clue who we were or what was going on. The underground thing was happening, but they were all retired colonels and members of the board. They lived in a universe that had disappeared by then.”

Born just outside Leeds in 1941, Chapman started on the local folk scene, juggling a musical career with fine art studies. For three years he taught photography at a Bolton college, before picking up the guitar again and heading down to Cornwall. It was there, in 1967, that he began nurturing his reputation. “I’d be playing at The Counthouse, while people like Ralph McTell, Wizz Jones and Pete Stanley were up at The Folk Cottage. The only place you could play acoustic guitar was in the folk clubs. In those days there wasn’t a PA, so you just tried to get the loudest guitar you could find. Wizz was a bit suspicious of me because I didn’t play like anybody else. I was kind of looked upon as the fastest kid on the block.”

One night he was spotted by a talent scout for publishers Essex Music, which in turn led to a deal with Harvest for 1969’s shape-shifting debut, Rainmaker. It was clear from the off that Chapman was very much a modern stripe of singer-songwriter. Like Harper, John Martyn or Bert Jansch, his laconic songs, mostly streaked with themes of regret and loss, defied easy classification. Though more often than not he was dubbed a folkie.

“One thing I’ve never been is a folk singer,” he refutes today. “People have called me that all my life and I still hate it. I never came out of that folk process, I came out of jazz and blues. I always wanted to be Big Bill Broonzy or Big Joe Williams or Lightnin’ Hopkins. And play a bit of jazz like [bebop player] Kenny Burrell and [Blue Note guitarist] Grant Green as well. I don’t know that much about folk music, except for the fact that most of it bores me to tears.”

The story of how Mick Ronson came to play on Fully Qualified Survivor is precious. Struggling to make a crust as a guitarist, he was mowing the lawn of a local school when old mate Rick Kemp passed by, on his way to Chapman’s album session. “I wanted to get hold of Mick, because I’d heard him play with [Hull band] The Rats,” recalls Chapman.

“Rick knew him better than I did, so he said: ‘C’mon, we’re going down to make a record with Michael.’” Producer Gus Dudgeon, fresh from working on David Bowie’s Space Oddity and Elton John’s second album, had already drawn up a list of potential guitarists from the London session scene and was resistant to the unknown Ronson. “Gus didn’t want him on there, but I said: ‘No, I’m bringing this gardener from Hull. I like the way this kid plays. He’ll fucking kill ya!’” Soon after, Chapman introduced Ronson to Bowie, who now had his right-hand Spider.

Later in 1970, while Bowie’s new guitarist helped record The Man Who Sold The World, Dudgeon recommended Ronson and Chapman to Elton John for his new opus, Madman Across The Water. The pair, according to Chapman, more or less took over the original sessions, though by August 1971, the singer-pianist had assembled his own band for the final cut. It was only much later that Chapman received an alarming confession from Dudgeon.

“At some point in the 90s, my wife was having dinner with him and his missus,” he explains. “Gus told her: ‘Elton says that Michael was always his first choice as guitar player in his band.’ But Gus had told him I wouldn’t do it! It would’ve been nice to have at least been asked. I remember at the time Gus asking if I knew of a guitar player who could do acoustic and electric, so I suggested Davey Johnstone. He must owe me about three million quid and a house in California by now.”

But would Chapman have accepted Elton’s offer? “No. I would’ve been the wrong guy. I’m not a rock guitar player, unlike Mick Ronson. Coming out of the jazz world, I like it clean and loud. And I always liked just being me and doing my own thing.”

Post-Wrecked Again, the remainder of the 70s found Chapman unfurling his sonic experiments on the Deram label. By 1978 he’d released an instructional album, Playing Guitar The Easy Way, and struck up a lasting friendship with US iconoclast, and touring partner, John Fahey. “A trouble magnet,” Chapman laughs. “Fahey could start a fight in a phone box. He was crackers, but once you figured that out it wasn’t so bad. I have a great video of John taking his coat off and trying to play guitar at the same time.”

Now permanently saddled with the stigma of ‘cult artist’, the following decade saw his sales dwindle further. As did his output. By his own admission, it was a fallow creative period. At one point he briefly ended up in a German jail.

“The 80s are what my missus calls ‘Michael Chapman: the Missing Years’,” he says. “It seems like we all have to misbehave to such an extent that you just go haywire for a time. It was down to drink and drugs. How much was I drinking? Too much to count, let’s put it that way.” He only pulled himself together after wife Andru threw him out: “I was sleeping in a shop doorway in Scarborough. Believe me, it’s not a great place to wake up.”

The 90s saw him rejuvenated, honing his technique to allow more ambient spaciousness in his sound. Albums arrived at a rate of knots, his guitar experiments sometimes sprayed with sequencers or industrial noise. 1995’s Navigation was arguably his best since his Harvest work. Chapman continued to record into the millennium, delivering restless soundscapes like Words Fail Me and Americana. By which time he’d begun to attract a new generation of admirers.

Suddenly he became hip. Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore declared himself a big fan. Chapman toured the US with late guitar innovator Jack Rose; Seattle label Light In The Attic issued remastered versions of Rainmaker and Fully Qualified Survivor, alongside a two-CD compilation, Trainsong: Guitar Compositions 1967-2010, though his status as godfather to a fresh breed of ‘American Primitives’ was sealed with 2012’s tribute album, Oh Michael, Look What You’ve Done: Friends Play Michael Chapman. Guests included William Tyler, Hiss Golden Messenger and Meg Baird, along with relative veterans Thurston Moore, Lucinda Williams and Maddy Prior. “I was amazed,” says a still incredulous Chapman. “That tribute album was put together by my wife. It took her two years and I never got a smell of it. Thurston jumped in straight away and she got everyone else to do their tracks. She just gave it to me on my birthday.”

Moore’s Ecstatic Peace! imprint also provided a home for a new pair of improvised Chapman albums, The Resurrection And Revenge Of The Clayton Peacock and Pachyderm, both styled after the avant-minimalism of his late friend, John Fahey, while earlier this year, he and Moore travelled around the UK on the Acoustic Fire Musics tour. Both men had a blast.

“Thurston is a delight to work with,” Chapman offers. “At the end of each night we both got together and were just torturing guitars.”

It’s been an unlikely, if hugely deserving, renaissance for a man who’s spent most of his career in the wilderness. And the 72-year-old is making the most of it. A third improv set is due soon, there are plans to reunite with arranger Paul Buckmaster in California and the possibility of recording with US underground artist-producer Jim O’Rourke. Factor in a stirring reissue of 1971’s Wrecked Again and Chapman is enjoying the balmiest of Indian Summers.

Not that he’s pushing any of it. “The one thing I learned early on in this business is not to make any plans, because they don’t work. Just go with the flow and see what happens. And it’s been a pretty good ride sometimes. I haven’t written a song for over three years. But then I’ve written over 300, so maybe that’s all there is in the tank. Or maybe it’s because I’m just too fucking happy these days.”

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 189