At the turn of the millennium – and not for the first time in rock history – there was nowhere cooler than New York City.

For the hipsters rifling vinyl crates in the East Village thrift stores, the essential soundtrack was Is This It by The Strokes, all trash-can guitars and curled-lip anthems howled through a glitchy microphone. But in the wee small hours, when the city fell to ink and neon, Interpol came out to play.

Debuting in 2002 with Turn On The Bright Lights, these four sharp-suited shadowmen made music that sounded like rain on a coffin lid, with frontman Paul Banks’ sombre proclamations met by the desolate, delay-clad riffing of Daniel Kessler.

But it was 2004’s follow-up, Antics, that stands as arguably Interpol’s greatest work to date, its stately melancholia and sudden explosions of violence casting an enduring spell in the age of throwaway landfill indie.

As such, two decades and seven albums later, the still-questing band wound back the clock with the Antics anniversary tour. And when we visited the Bristol Beacon to meet Kessler – now an impeccably tailored 50-year-old – we found him on the tightrope between past and present, debating how to balance his youthful gear choices and musicianship with the artist he has become.

What do you remember about the road to the Antics album?

“We’d been a band for five years. Nobody was really rushing to sign us. Plenty of record labels had rejected our demos, including the label we eventually signed to, Matador, who had rejected our first three demos. Antics really came on the heels of 2002’s Turn On The Bright Lights: we never stopped between the two records.

“We were touring Bright Lights, then we got back to New York and went into a little rehearsal space in Brooklyn and we started writing Antics. A week or two later, the new songs were moving forward.

“The idea was to write the next chapter without overthinking it. We were putting our heads in the sand, just trying to stay focused on the music and not how it resonated. I think Antics solidified that we weren’t a one-hit – or one-album – band.”

Antics sounded so different to the prevailing music scene of 2004. What did you want Interpol to be?

“With the first record, we’d maybe been lumped into certain musical categories. And it wasn’t exactly a motivating factor – we’re gonna write what we’re gonna write, no matter what – but I think we wanted to show other sides of the band. Y’know, even starting off Antics with a song like Next Exit – I mean, you can’t call that a ‘post-punk’ song. It’s just not.

“It felt more like something from the ’50s and ’60s, or a song by Roy Orbison, who we were all gigantic fans of. I think these things had always been in the band, but Antics gave us the opportunity to dive deeper. For me, a song like Take You On A Cruise or Not Even Jail is a good illustration of that.”

You once said that you’re not “a big major chord person”. Could Interpol ever write a genuinely happy song?

“I mean, Slow Hands is probably the closest thing that we have to a major-chord moment. I guess the short answer to that is – no. But I have no aversion to major chords, if they really attract you.”

What was the atmosphere like in the studio when you were recording Antics?

There was intensity, passion, decisions to be made. I think when you’re making a record, it can go terribly right or terribly wrong

“There was intensity, passion, decisions to be made. I think when you’re making a record, it can go terribly right or terribly wrong. Sometimes there’ll be a song you think is pretty straightforward and you’ll be like, ‘Why is this song having such a hard time expressing itself or being what it wants to be? In the rehearsal space, all the parts were mapped out, but right here in the studio it’s just not doing its thing.’

“Then there are the songs you feel are going to be really difficult because they’re complex or have tempo changes – and it’s one take, there it is. And I think that’s a beautiful thing about music. You think something is going to happen according to the blueprint and it doesn’t.

“But beyond that, there’s always been a lot of laughter, easy banter, inside jokes. It’s important to have that. We’ve never been in a situation where we’ve made a record that’s been painful or had no chemistry.”

You’ve always said you want your guitar parts to be supportive, rather than flashy. Where did that ego-free philosophy come from?

A band like Fugazi changed my perspective. That band is easily the biggest influence on me

“Music has been a constant in my life. I shared a room with two older brothers who were really serious and passionate about it – certain bands were almost more like a religion. Through them, I got to hear really underground music when I was in single digits. But I think the biggest factor was living in Washington DC and being super into the underground music scene.

“A band like Fugazi changed my perspective. That band is easily the biggest influence on me. Listening to how those two guitarists [Ian MacKaye and Guy Picciotto] worked together – it fascinated me that one of them could just hit the same note throughout the song, while the other guitar has a lot of movement, but that one note added so much dimension and depth and texture.

“I’m a minimalist. You can make an impact with very little. I always felt like a songwriter on the guitar, rather than a guitarist per se. Paul is a really good guitarist and he’s also constantly evolving as a player.

“I think he’s way more exploratory and expansive than I am. Paul played a lot of the lead on Antics. A lot of the solo guitar stuff would be him, and I’m more like the rhythmic stuff.”

Two of the best-loved songs from Antics are Next Exit and Slow Hands. What can you tell us about writing those?

“Next Exit is one of the songs we came up with together in our rehearsal space, years before Antics. We’d just got a new keyboard, so Carlos [Dengler, bass] was playing those chords.

“We originally wrote it to be an introduction when we went on stage, before we were even signed and still playing bills with five other bands; same thing with Untitled from the first album. They were these introductory pieces, like a palate cleanser to announce ourselves, then later we fleshed them out and made them into songs.”

“I remember coming up with the riff for Slow Hands sitting on my couch with a classical guitar. I write most things on that guitar – I’ve been doing it since I was a teenager. I’ll watch films and just let my mind wander without thinking about what my hands are doing. My mother bought that classical at a local guitar shop and it’s crap, it’s terrible. But there’s something about it.

“It’s a little bit smaller around the body. It’s very comfortable. But it doesn’t sound good, so, to me, if an idea comes from that guitar, it really has to jump out at me. It has to demand my attention for me to want to build something around it. Sometimes, I feel like when you plug into a great setup with effects and reverb – it’s almost too comfortable.”

When we were touring Antics, I was using Twins live, but for that record I really leaned on a Princeton

What was your guitar amp setup for Antics back in 2004, and how faithful is your rig for the anniversary tour?

“It’s actually very faithful. For the first two records, we were recording with Peter Katis [producer] and he had an old Fender Princeton. I’d blend that with some other crazy amps, maybe a Gibson, maybe a [Carr] Skylark – and some other things that I haven’t seen before or since.

“I think that’s where I really developed a love for Princetons and, consequently, why I bought an old Princeton, a ’68, which I still have. When we were touring Antics, I was using Twins live, but for that record I really leaned on a Princeton. And now, I’m playing Princetons live, since Fender reissued them. So, if anything, my setup is more faithful to Antics now.”

What was your choice of guitar then, and what are you playing now?

“I used an Epiphone Casino for both Turn On The Bright Lights and Antics. For this tour, it’s not the exact same guitar – because I don’t have that any more. It was a terrible tour lesson. It was stolen out of a dressing room, because of bad security, in Vancouver. I was really heartbroken.

“But I’m a creature of habit and for the Antics shows I’m using a Casino from around the same time period, a ’67. So I have my Casino from ’67, my Gibson 330 from maybe ’68 – and I also have a 1960 Gretsch Anniversary. The output on that guitar is so low, you have to really dress it up with the right support in terms of pedals.

“When I plug it in, it doesn’t shine on its own. But the pedals really bring it out and I do think there’s something about that guitar and its age – it just has so much character.”

That hollow and semi-hollow body format seems to be a constant across your career. Why does it work so well for you?

“I think the reason I fell for Casinos – much like the Gretsch – is that it’s a timeless sound that you’ve heard since the ’50s and ’60s. There’s just something very sincere, genuine, emotional and vulnerable about that sound. And, for me, I think that sound has always been my calling.

“Even with Ennio Morricone’s Spaghetti Westerns – hearing those guitar sounds in films as a kid, I just wanted that. I can’t say for sure, but, to me, that sound sounded like a single-coil pickup. I’m not a humbucker person, I’m a single-coil guy. It’s like picking out a shirt and saying, ‘That’s my style.’”

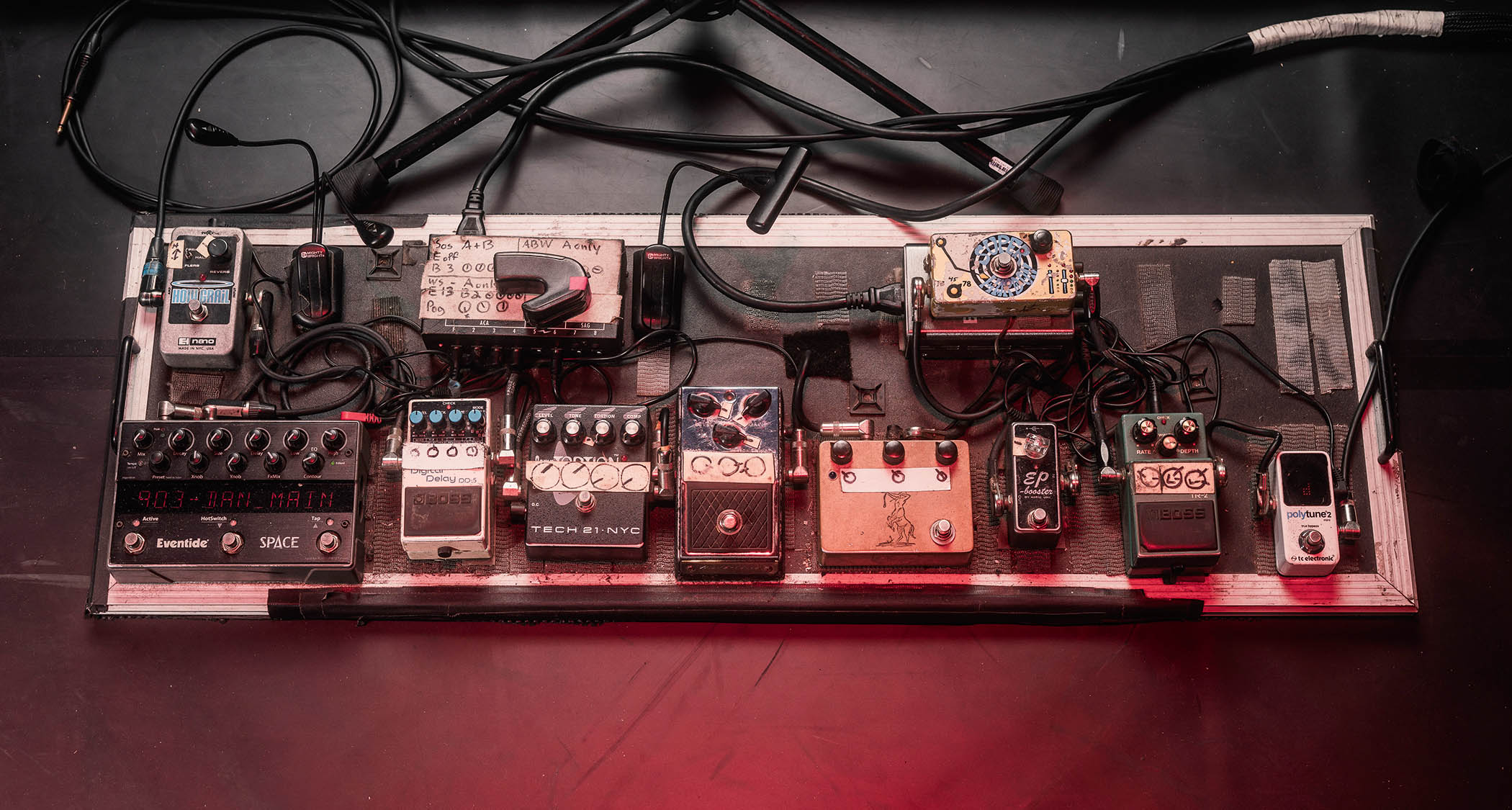

Your sound is so atmospheric – how many pedals does it take to get you there?

“It’s actually pretty stripped. I probably could use a little more courage, to go to a guitar store and set up in a little room for a while and just go through 20 pedals and find new discoveries. I really like the Vox Valvetone, which is on Antics, and I still play that quite a bit. I’m still using a Boss DD-5 on this tour.

“As much as there’s amazing analogue stuff now – it’s definitely come a long way since we were starting out – there’s something about the DD-5 that’s very singular to that Antics sound. I don’t switch out pedals too often.

“There’s usually only one or two things that are different every few years. Whereas Paul is always discovering new pedals that I’ve never seen anywhere else. He’s not beholden to the past.”

You’ve said in the past that you have no interest in becoming a technically dazzling guitar player. So how would you like your playing to evolve from here?

The plan is to write and record the next Interpol album in 2025

“For me, it’s really about songwriting. And I’m not tired of that at all. If the well felt a little dry as far as finding new things, then I wouldn’t force it, I’d take a big break, I wouldn’t push things. But it doesn’t feel that way to me.

“The plan is to write and record the next Interpol album in 2025. So it’ll be a fun next few months of touring and finishing these Antics dates – but then I’m really looking forward to switching mind frames and really getting into the next chapter.

“I think what motivates me now is the same thing that motivated me as a teenager: there’s no greater feeling than when you come up with something new.

“Artistically, that’s the best thing, when you go, ‘This is the best thing we’ve ever done.’ And I feel like as artists – whether people agree or not – you should be the most excited about the last thing you did.”

- Antics is out now via Matador.