There’s no point beating around the bush. I am talking to the director Robert Zemeckis, who won an Oscar in 1995 for Forrest Gump, about his new film Here, which opened in the US in November to some of the toughest reviews of his career. “It’s a film so soulless I questioned the point of it,” ranted Screen Rant. The New York Observer called it a “meandering bore”, while trade paper Variety homed in on the film’s “disappointingly generic” portrait of its characters. It seems life isn’t always like a box of chocolates, to misquote Gump.

Here’s box office was dented by the reviews in America, scraping around $12m (£9.75m). But is Zemeckis stung by the critics? “Well, sometimes you learn from the criticism and you understand what the criticism is,” he replies with a shrug, “and sometimes the criticism is completely unfounded, and then they’re criticising something that is absolutely perfect but they just don’t like it. So you have to just dismiss that and not even worry about it. I mean, everybody does the best that they can with the tools that they have. And criticism... is its own thing.”

Zemeckis has been here before. When he made 2004’s The Polar Express, the story of a young boy’s journey to the North Pole via a magical train, the critics laid into the motion-capture animation (including a computer-generated Tom Hanks as the conductor), practically spawning the phrase “uncanny valley” to express the eerie not-quite-human-enough look of the characters. Yet the festive film still took $318m worldwide, a perfect example of how the public tend not to agree with critics when it comes to an assessment of Zemeckis’ work. His finger has frequently, successfully, measured the populist pulse.

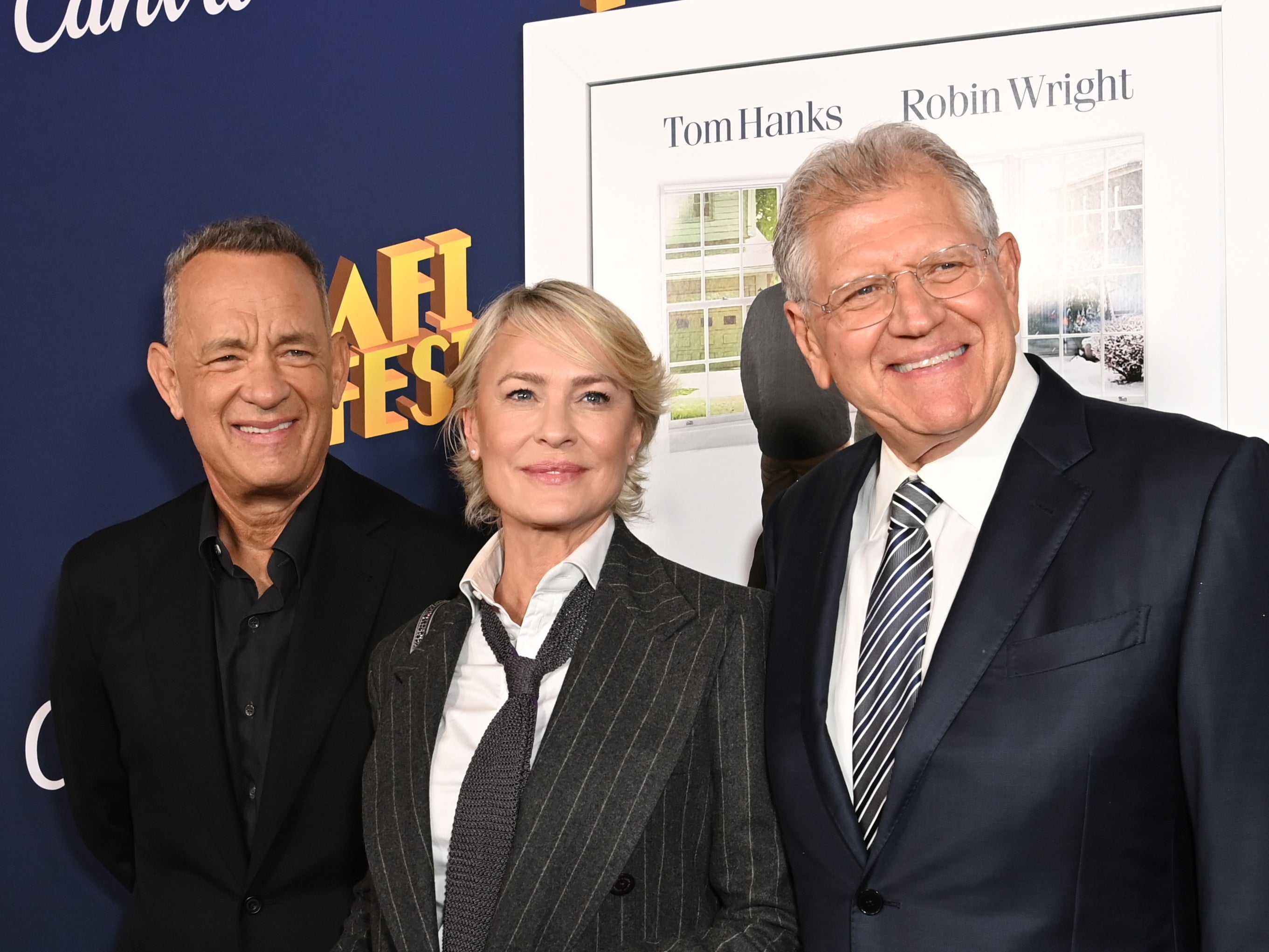

Here reunites Zemeckis with Hanks and Robin Wright for the first time since they made Gump, his tale of a good-hearted, life-lesson-dispensing rube. It also sees him back with Eric Roth, his Gump screenwriter, as they tackle Richard McGuire’s 2014 graphic novel – a story that spans centuries while exploring the lives of various characters, all of whom have occupied the same spot of land in Pennsylvania. Among the inhabitants of this single space of Stateside soil are a Native American couple, the inventor of the La-Z-Boy armchair, and an alcoholic Second World War veteran, played by Paul Bettany.

Hanks plays Richard, the son of Bettany’s character, opposite Wright’s Margaret, and the couple fall in love, marry, have children, and face typical relationship complications as they get older. In a narrative composed of episodic vignettes, their trajectory is the most substantial, its overly sentimental story chiming with Zemeckis’s beloved themes of family, nostalgia, isolation and loneliness. “I think that filmmakers very often have to speak from their heart,” says Zemeckis, a committed family man, who has three children from his second marriage to actor Leslie Harter.

We’re speaking over Zoom, Zemeckis framed in a small window on my computer, which feels particularly apt given the aesthetic visuals of Here – a film that moves between its various narratives via rectangular-shaped windows that pop up on the screen, signalling the forthcoming action from another timeline as the story skips about. Humble in person, the bespectacled 72-year-old talks enthusiastically and warmly, even if some of his answers can be as sentimental as his films.

Zemeckis is particularly gushing about his actors. “What stays with me on this film is very much working with the beautiful cast that I had,” he says. “To me, that’s going to stay with me for the rest of my life. Completely.” He’s worked with Wright four times, while his collaborations with Hanks stretch to five, the last being his fumbled 2022 adaptation of Pinocchio, in which Hanks played the woodcarver Geppetto. All the same, theirs is one of Hollywood’s most fruitful pairings, with box office takings close to $1.5bn, and there’s something about Hanks’s likeable everyman persona that dovetails perfectly with Zemeckis’s wholesome all-American veneer.

I was fortunate enough to have both of my first choices, actor and actress, agree to make the film

So it’s strange when he claims that he wasn’t thinking of Hanks from the off for Here. “When I’m writing, I don’t know who the actors are. I always write shadows,” he says, before launching into a statement that feels a little disingenuous. “Then I started thinking about who the cast might be, and Tom Hanks for that character was my very first choice. And I sent him the script, and he immediately agreed to do it, which was a thrill for me. And then my next first choice for Margaret was Robin, and the same thing happened... I was fortunate enough to have both of my first choices, actor and actress, agree to make the film.”

Zemeckis – who was born in Chicago and now lives in California – is behind some of the biggest Hollywood movies of the 1980s and 1990s, including the Back to the Future trilogy, Who Framed Roger Rabbit, and Death Becomes Her. A master of the thrilling set-piece – take, for instance, a drugged Michelle Pfeiffer drowning in her own bath in What Lies Beneath (2000) – he’s also proficient at stretching the medium. Think of the groundbreaking live-action/animation hybrid in Roger Rabbit, as Bob Hoskins’s gumshoe is tormented by Looney Tunes cartoon figures. Or the one-man desert-island survival tale Cast Away (2000), also starring Hanks. Or his pioneering forays into performance capture, by which he films actors and then computer-animates them – as he did with his Yuletide tale The Polar Express and his Dickens adaptation A Christmas Carol (2009).

Here also gave him the perfect platform to push the cinematic envelope, and for all its lack of character depth and emotional resonance as it tries to convey life’s fleeting, fragile moments, it’s a daring attempt at something new. With the camera fixed in one position – in the corner of a suburban living room in the film’s more contemporary moments – it’s effectively a single-shot movie as the action flicks between centuries and storylines.

For Zemeckis, making a movie without ever moving the camera was a hugely challenging assignment. “You might think when you start that it’s easy, but once you start to really realise what needs to be done – meaning that every single scene in the movie must work within this one singular view – it then becomes an incredible amount of pre-production, and figuring out exactly where everything is going to be, and exactly where the corners of the walls in the room are going to meet, and where the window is going to be positioned, and what exactly is going to be outside the window.”

Here also raises the topic of artificial intelligence, with Zemeckis using a generative AI tool from VFX studio Metaphysic to de-age Hanks and Wright – not unlike the technique used in Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman, where Robert De Niro et al had the years knocked off them. Zemeckis faced criticism for taking Hanks’s Richard and Wright’s Margaret back to their teenage years, just as he did for the CGI he employed in The Polar Express. “The results look anything but natural,” suggested Variety.

AI, of course, was one of the key talking points in the 2023 Sag-Aftra strikes, which saw Hollywood grind to a halt as actors bemoaned the studios’ use of technology to effectively replace them. How does Zemeckis feel? “I mean, there’s many things that AI is going to do that we can’t think of,” he says. “What I learnt from making a movie about the future” – by which he means 1989’s Back to the Future II, set in 2015 – “is that we always underestimate it when we try to predict it. I use [AI] to create digital makeup, and that’s what I use it for.”

Avoiding making any grand pronouncements, he adds: “I don’t really ever try to predict the future when I’m making a film... I would never be presumptuous enough to try to predict what the future is going to be as far as where technology is going, because it’s moving so quickly. I wouldn’t be able to figure that out at all.”

Zemeckis has tinkered with visual effects ever since he was a boy, making 8mm films in the home he shared with his folks in the 1960s. Ever the innovator, he eventually won a Student Academy Award for his 14-minute short A Field of Honor. The story of a shellshocked ex-solider released from a sanatorium, scored to the theme from The Great Escape, it caught the eye of one Steven Spielberg, who was so impressed he went on to produce Zemeckis’s early films I Wanna Hold Your Hand (1978) and Used Cars (1980), which starred Kurt Russell as an underhand automobile salesman.

Since then, Zemeckis has regularly been cast as one of Spielberg’s protégés (the Back to the Future films were all produced by the latter’s company Amblin), although it could be argued that he takes more risks than his erstwhile mentor ever did. What’s left for a director who has seemingly done it all? Zemeckis recently told the Happy Sad Confused podcast that he’d love to return to the Back to the Future universe – something he’s resisted for decades – and adapt the hit Back to the Future musical for the screen. It would be intriguing to see him revisit that world.

But as Here tries to teach us, life is short. “Oh, life is definitely too short,” nods Zemeckis in agreement, “but I’m very grateful that I’ve been able to do what I’ve wanted to do.”

‘Here’ opens in cinemas on 17 January