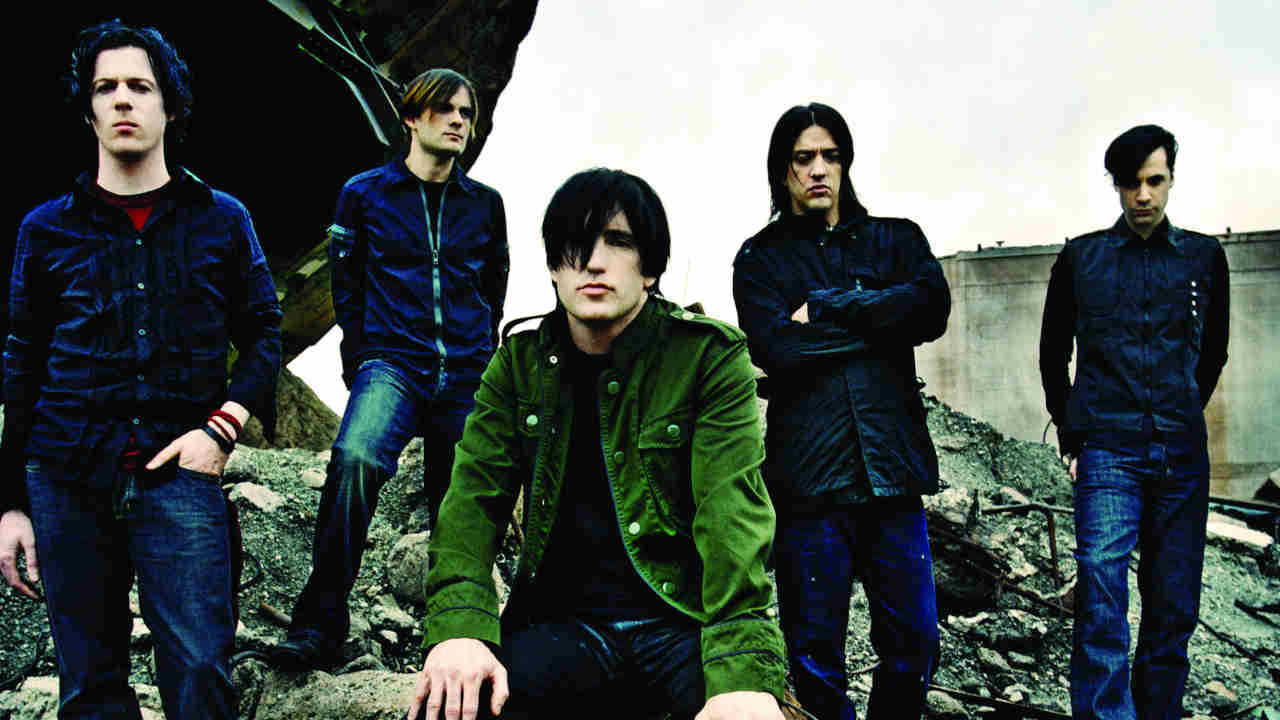

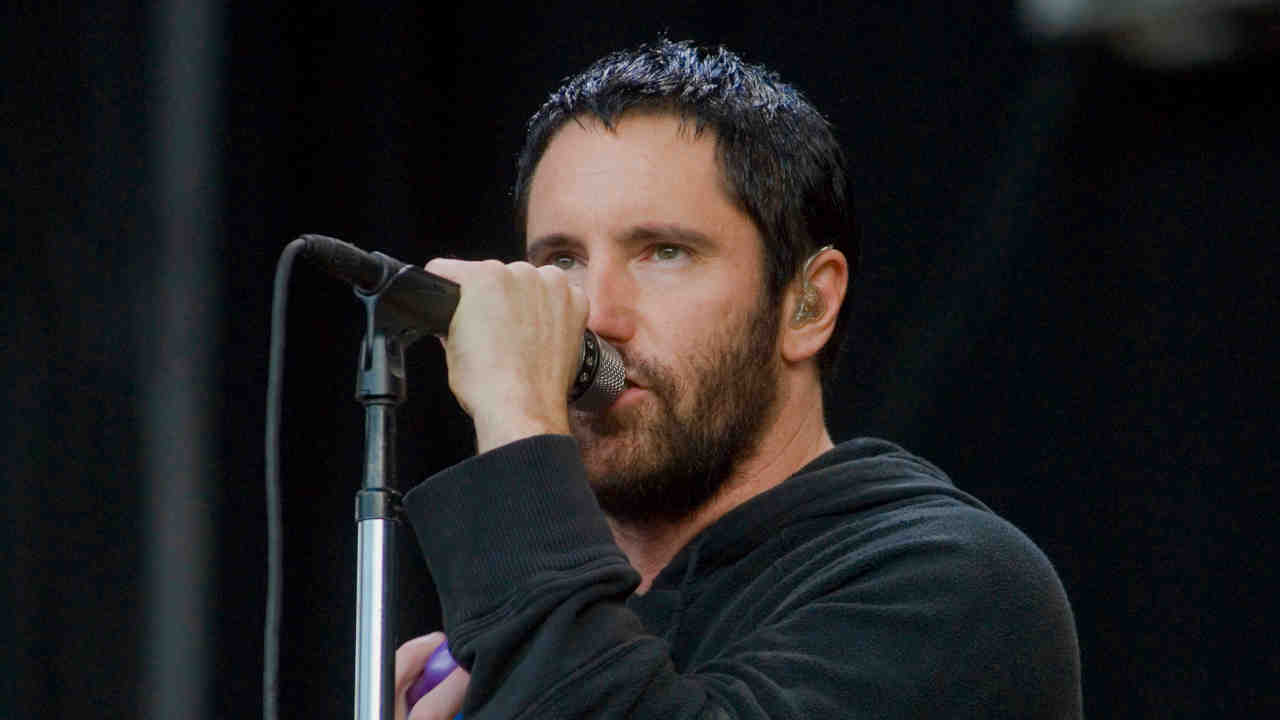

Nine Inch Nails’ Trent Reznor is one of the most influential and acclaimed musicians of the last 35 years, his journey punctuated by the epic highs of success and the crushing lows of addiction. In 2005, as NIN released their fourth album, With Teeth, Reznor talked Metal Hammer through his rollercoaster life and career

“I needed to do something or I wasn’t gonna be around.” The gym-buff biceps and twinkling eyes of the man draped across the plush Park Lane sofa don’t look like they belong to someone recently scratching at death’s door. But for Trent Reznor, reluctant icon of industrial rock, the last decade has been – to quote one estranged friend, “a long hard road out of hell”.

The one time chemically-braced berserker behind Nine Inch Nails is now a courteous, thoughtful Evian-sipping soul. Like the 12 Step survivor he is, he’s prone to lengthy self-analysis. The answer to one question can last 25 minutes – a possible shield against being asked another (that way, Trent maintains control). Dig too deep, and he’ll puff his cheeks and blow, “That’s a tough question…”

Reznor is speaking to Metal Hammer due to a sudden burst of renewed NIN activity, which includes an enhanced edition of the classic The Downward Spiral and the release of an excellent new album, With Teeth – a record for which NIN fans have had to endure a six-year long wait.

“What took this record so long? I needed to clean up. Get my life in order. And after the last tour in 2001, I was a mess.”

And if this sounds melodramatic, Reznor assures us it’s not. “It wasn’t gonna be another way. It was gonna be the end.”

To understand how Trent Reznor nearly met that premature end, we need to go back to his beginnings.

You begin to understand the trapped rage of Nine Inch Nails’ early music while flying over the American Midwest. Tiny sporadic settlements are separated by mile after endless mile of square farming fields. Trapped rage may be an essential requirement in rock’n’roll these days, but for Michael Trent Reznor, born almost 40 years ago in rural Pennsylvania, and raised by his grandparents in the arse end of Ohio after his parents divorced, there were no reference points. This was an age, and a place, that left you completely fucking isolated.

“I don’t wanna paint a picture of a terrible childhood,” Reznor is at pains to point out. “I had a loving family. But where I grew up was pretty much in the middle of nowhere. It was pre-internet, and I’m trying to work out how much that would change things – probably quite a lot. It was pre-MTV. There was no college radio. The only real way of getting stuff was Rolling Stone magazine, which was not as ass-kissingly corporate as it is now, but it certainly wasn’t cutting edge.

“You could see your destiny. People talked about ‘high school, the best years of your life…’” he continues. “Well, it sucked for me! I didn’t fit in. I wasn’t praised for throwing a football or whatever. But for a lot of people it’s the last bit of freedom before settling into the 30 year mortgage. ‘Be realistic. She’s good enough, marry her.’

“It came back to haunt me, I felt inadequate. ‘What do I know? I’m from a little farm town in the middle of nowhere.’ I later used drugs and alcohol to compensate for that.”

Did a small-town upbringing have any benefits?

“If I was in an urban environment I would have probably become an addict a lot quicker. There weren’t many drugs around where I was growing up. Though later I found out that the local Amish Dutch [a reclusive Christian sect who live a strict 18th century lifestyle] community were running a cocaine ring. Those clever little fuckers. That would have been as convenient as Hell, but I didn’t know. Who would have imagined there was a couple of bricks in the back of the horse and buggy!”

Reznor’s desire to escape was fuelled by the “impenetrable world of TV”.

“You can’t get to that world if you live here – sorry!’ Looking back – through a romantic haze – it was TV that drove me to plan how the fuck I was gonna get out of there.”

The answer, of course, was music. There were a few low-grade garage bands – they didn’t come to anything. And then Trent, a classically trained pianist in his teens, got a job as a cleaner in a studio to pay for some demo sessions which, in turn, got him signed to TVT Records (a label with whom he would later fight a bitter dispute).

The result was Pretty Hate Machine, a debut album that, with the help of singles Sin and the anthemic Head Like A Hole, eventually sold gold. As dark as Ministry but as catchy as Depeche Mode, it featured what would later become trademark Reznor lyrics about manipulation and betrayal – the sound of a young man making sense of the music he grew up with.

“I haven’t sat and listened to Pretty Hate Machine for a while. I was in a transitional phase. My first record. I didn’t know how to write or arrange songs or how a studio works, but I got a deal. And I wanted to work with someone who could take the music further out.”

His first choice, Adrian Sherwood (dub-rock producer who worked on Ministry’s Twitch – one of Reznor’s favourite records), was refused by TVT for being relatively unknown. Eventually they compromised with John Fryer (who had worked with ethereal 4AD acts like This Mortal Coil), and Flood (U2, Depeche Mode).

“It’s a record that, at the time, felt like the best I could do.”

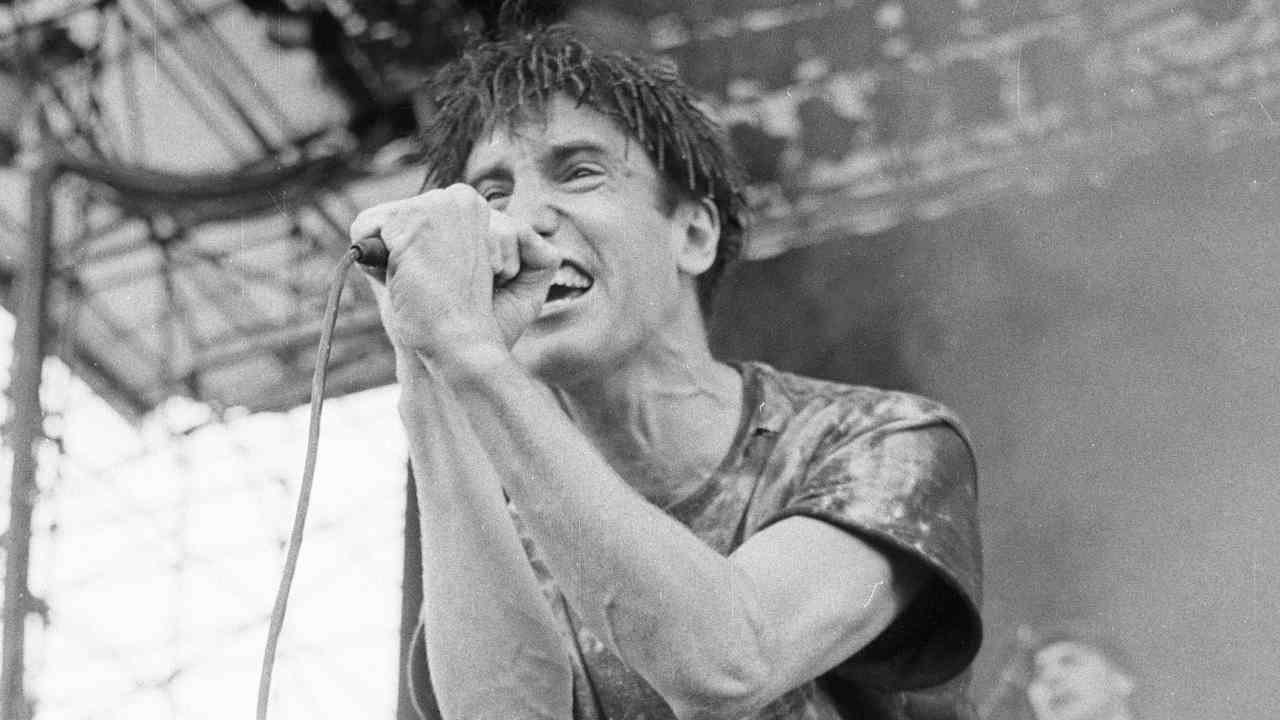

When the time came to perform his primarily electronic, digital songs live, notably on Perry Farrell’s 1991 Lollapalooza tour, Trent was forced to view his music in a new light.

“Playing live is a whole different animal,” says Trent, who shelved the DAT machines for “real people sweating, and don’t worry if it doesn’t sound like the record so much.

“The response was violent – I screamed, and people screamed back. I was way too anal, way too studio, up my own ass. I needed a more visceral flex of the muscle. That’s primarily why ‘Broken’ sounded the way it did.”

The Broken EP, or mini-album (and its remixed version Fixed) was Reznor’s first stab at independence (by now, TVT had been swallowed by Interscope, though Trent’s own imprint, Nothing, was appearing on NIN releases), his first fuck-you to record company meddling and, arguably, his first great record.

“Broken was recorded kind of in secrecy. The record company were interfering in a way I couldn’t put up with. Instead of saying, ‘OK, we didn’t understand. Just do what you do, we’ll sit back and take your money.’ They said, ‘You sold a million records, now we’re gonna sell four million, but you’re gonna use this guy.’ It came down to, I’d rather kill Nine Inch Nails after one album and an EP than make records with Fine Young Cannibals because they happen to be in the charts that week.”

Trent won the argument, with staggering results. Broken, and most notably its exhilarating pivotal track Wish, focused the NIN sound like sunlight through a spyglass. Lyrically laced with dark humour (“Don’t think you’re having all the fun/You know me I hate everyone”), where Pretty Hate Machine was angry at the world, Broken’s knives were directed inwards: ‘I’m the one without a soul, I’m the one with just this fucking hole.’

“That’s the entrance of that, yes,” he says. “That turned into The Downward Spiral.”

There were three great quasi-suicidal, misanthropic angst-rock masterpieces released in 1994 - Nirvana’s In Utero, The Manic Street Preachers’ The Holy Bible and, perhaps the most underrated of the bunch, Nine Inch Nails’ The Downward Spiral.

Recorded in 10050 Cielo Drive, the Hollywood house where Charles Manson’s ‘Family’ murdered actress Sharon Tate (Reznor maintains he didn’t know this when he moved in), The Downward Spiral was a draining emotional journey in which a brutally honest Reznor dealt with all manner of demons.

“It was about me, but a projection of me, a character who systematically destroys all these different things in his life in the search for some sort of answer. And in the crossfire is… sex, relationships, trust, the spectre of religion and its flaws and its lies and its hollowness, and drugs, and a sense of purpose, and self-loathing and desperation…”

Its most famous song is its finale, Hurt – as covered so heartbreakingly by Johnny Cash, the original Man In Black, on his American Recordings swan song.

“Hurt was the last song I wrote,” Reznor reveals. “And it nearly didn’t make it on. But I felt the record wasn’t finished. There was this sense of remorse, like I’d smashed everything in the room and was sitting in the middle of a pile of broken stuff, and I’m not sure what I’ve done and maybe it wasn’t the right thing to do. Then the record comes out, and that becomes my life, or my life becomes that record. Almost to a tee.”

The Downward Spiral was a massive success, selling platinum and Reznor threw himself into touring the album (NIN’s mud-spattered performance at Woodstock 2 was universally hailed as that festival’s highlight). Behind the scenes, Trent was going off the rails big time.

“I wasn’t prepared for the whirlwind that follows a hit record, emotionally or mentally. I was at my most miserable when I had everything I ever wanted. I’m not saying it’s a terrible thing – it’s a great thing – but when every aspect of your life changes, you can’t sit back and watch it, you can’t understand it. You’re in the cyclone.”

Enter Trent’s little helpers, in liquid and powdered form.

“I was in one of the biggest bands in the world, and still felt like I wasn’t good enough. I’d walk into a room with five people in it, and feel completely intimidated, like my skin was on fire... I wasn’t good enough. The quickest way to deal with that was to have a drink, and the fire went out – ‘I’m funnier than I was a minute ago, and more interesting.’”

And cocaine, of course, suppresses the self-doubt.

“Temporarily. Then there’s a lot more self-doubt. It’s a good 15 minutes though… then you get off the tour bus two years later thinking, ‘Who the fuck am I? And who are all these people around me?’ ‘I’m the guy that’s in the magazine, right?’ You become a scarecrow, a projection of what people read into you.”

Reznor has never courted celebrity. Apart from a brief and acrimonious professional and personal relationship with Courtney Love, he doesn’t have a high-profile private life.

“It’s about knowing when to say ‘No’. It’s not like it was when I was growing up. There’s the internet now, and MTV, and music channels pumping shit. There is a way to over-expose yourself. I don’t seek mystique – it’s not that I’m afraid of people finding out stuff about me – but giving away too much is a bad thing. Maybe if you’re, I dunno, Creed, it doesn’t really matter. But if you do something with some depth… I’d rather you were curious, than sick of hearing about me.”

As a result, Trent can walk around mostly unmolested by the public.

“Around the time of The Downward Spiral I got hassled, but less now. I usually go around as a woman, which throws people off. I’ve tried to make a point of not letting my personality become...” He chooses his words carefully. “I’ll say this, I think there are certain people whose personality gets in the way of the music. And maybe their personality is what’s good about them anyway. Not so much the music.”

Who can he mean? Marilyn Manson was being looked after by Trent some 10 years ago. Does Reznor feel like Dr Frankenstein eclipsed by the fame of the zombie he helped create?

“To some degree. I have mixed feelings about the whole thing, because from a business point of view, for the record label, it was wildly successful. I think he’s a talented guy, and I’m not taking credit where it’s not due. If there was a valid role I had, it was helping provide a framework to allow him to do what he wanted to do. And then the whole thing happened, and… what’s done is done. As a human, as a friend, I’m disappointed.”

Reznor signed Manson to Nothing Records in 1992, and MM became regular Nine Inch Nails tour mates and the pair became close friends. Manson’s autobiography The Long Hard Road Out Of Hell tells tales of he and Reznor indulging in drug-fuelled depravity (kidnapping, condiments, handcuffs, groupies etc), while the two bands worked simultaneously on Portrait Of An American Family and The Downward Spiral.

The duo disagreed over the musical direction Manson’s ‘Antichrist Superstar’ should take. Silly conflagrations ensued – Manson members smashing up NIN’s gear and vice-versa. The situation came to a head when Reznor stole the job of providing the soundtrack to David Lynch’s The Lost Highway from under Manson’s nose.

“I’m not blameless for sure,” Reznor admits. “But part of it is… we were friends, I was helping him out, then he’s on my label, then he’s opening for my band... and the competitive nature of it got to him. You get tired of answering questions about your ‘big brother’. And when you sprinkle lots of money and drugs on top of that…”

He sighs, and repeats: “I’m disappointed. But you lose friends along the way.”

If Manson was unhappy about The Lost Highway, Reznor in turn was unhappy about the revelations in Long Hard Road… On NIN’s next album, The Fragile, Reznor wrote a song, Starfuckers Inc., clearly aimed at his former protégé: ‘I am every fucking thing and just a little more/I sold my soul, but don’t you dare call me a whore”. Ouch.

They did patch up their differences, to the extent that Manson joined Reznor to sing the song at NIN’s Madison Square Garden show in May 2000, and Manson even volunteered to direct and co-star in the video. But the feud resumed and Manson quit Nothing and signed directly to Interscope. They have not spoken since.

“We’re at different situations in our lives. There’s a toxic element to him that probably wouldn’t be healthy for me to be around.”

When the FAQ section on official website NIN.com asked if he had plans to record any cover versions, Reznor replied he was, “hoping to do something unique and pertinent – like an exact copy of Personal Jesus – but it was already taken.” Miaow!

“I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about him,” he says. “Until I’m in Europe and people ask me about him. Because you still remember him over here.” Double miaow!

For the first decade of his career, Reznor was something of a workaholic. As well as recording and touring with NIN, he ran a record label – whose roster included Meat Beat Manifesto, Plug, The The, 12 Rounds, Coil, Clint Mansell and NIN offshoot Tapeworm – and licensed Warp records in the US. He made the Lost Highway and the stunning Natural Born Killers soundtracks, contributed to the Tomb Raider and Crow soundtracks and the Quake computer game, remixed N*E*R*D and Bowie, collaborated with Tori Amos and, of course, produced Manson.

“I didn’t want anything in my life that wasn’t fulfilling my potential as an artist. I maybe had a gift, and I had an opportunity to make a career out of it. Every minute spent not working on music was a minute lost, which may be a noble way to look at life when you’re 23, but I’m still living that life and I’m 39. That’s what paved the way for me to become an addict. I found I could do things myself, and I didn’t think I needed anybody else. I didn’t need a friend, I didn’t need a girlfriend, I didn’t need a producer, I didn’t need a band. I’ll do everything myself. Fuck you!”

Unfortunately, by the time NIN came to make their third proper album, The Fragile, Reznor was every type of ‘holic going and very fragile indeed. A sprawling double, long on experimentation but short on lyrics (“I was more or less unable to write them”), recorded with Depeche Mode producer Alan Moulder, it’s NIN’s most flawed release. An unfinished record even?

“Tough question. I’m not just saying this to justify it, but it’s an accurate a snapshot of my life at that time. I made the best record I could, with the tools available and, I was terrified, I was overcompensating. I’m proud of it. It was made in insane circumstances, and the effort that went into it… it was camaraderie-filled. But I hope I never make a record like that again.”

Does it stand up now?

“I listened to it for the first time in a long time, and I can see where I was, and what was about to happen.”

Which was?

“I was the guy on the ledge, ready to jump. I had to get to a true bottom. That’s why the last two records took so long. This started in ’96 or ’97, and it took me that long to stop lying to myself and deal with it. I kept digging deeper until I was as low as I could go.”

Two events caused Reznor to hit rock bottom. Firstly, a friend of his was shot in the face (he only heard about it on the TV news), and subsequently, Reznor took a massive amount of what he thought was cocaine that turned out to be heroin, landing him in hospital in a critical condition.

“So, 2001 rolled around, and I was scared enough that… I was ready to do whatever it took. I wanted to continue to live. I didn’t wanna be that guy anymore.”

Like seeking help?

“I went to a treatment place, from 12 Step programs to meetings, to psychiatry. You name it. I wanted to be told. To listen for a change, to realise I don’t know everything – I don’t – and that sometimes giving up is winning, rather than defeat. I realised, when I’d detoxed and become physically un-addicted, that I needed to figure my priorities out.”

But he didn’t rush back into the recording process.

“One reason was fear. I didn’t know if I could write, if I could think. I didn’t know if I’d destroyed my brain. Also, I didn’t know if I had anything to say.”

Trent was relieved to find that, without his chem-dependence, his muse flowed even more freely.

“An interesting shift took place in the early stages of recovery – away from the addict life I was grieving – like someone flipped a switch and all of a sudden I’m swimming with the current.

“Before, I believed I could out-think this. ‘I’m too smart.’ And then you start to feel like your life is a Behind The Music episode – ‘Oh, I’m that guy. And there are a couple of guys I’ve turned into that I didn’t think I was.’ I didn’t think I was the addict guy and I didn’t think I was the guy whose manager took all his money (in 2004, Trent sued ex-manager John Malm for taking improper control of NIN’s finances). But now I’m this guy – and maybe I’m not so fucking special. Maybe I’m not such a unique case.”

With his confidence back, things happened fast.

“Suddenly all this stuff starts flying out of me, ideas which had been stuck in a clogged pipe. I’ve got a new set of tools and I’ve got a new brain, and every 10 days I can do two songs, finished! Regardless of what was gonna happen commercially – you know, ‘Will people like the record? Will anyone remember me?’ – being back on track was the main thing.”

With Teeth is, in many ways, NIN’s most accessible record yet. In addition to the familiar electro-metallic assault, it has one dancefloor-friendly track, Only, which boasts an infectious electro-disco groove.

“I’ve heard it criticised for being poppy and I agree. It’s accessible… and I like it. A voice popped up in my head and said, ‘You can experiment with this, but it probably shouldn’t make the record.’ Then I thought, ‘Fuck what people think!’ Last time around there were too many censors. The voices have kept quality control pretty good up to now, but there’s a fine line between quality control and terrified madness.”

And what next?

“I can’t believe all the time I wasted, being crazy. I’ve got another record almost finished now.”

So it won’t be a six-year wait this time?

“Well, I sure as fuck hope not! It won’t be for the same reason, put it that way.”

Originally published in Metal Hammer issue