Beloved of connoisseurs of progressive music, the Canterbury Scene was one of the most quietly influential musical movements of the late 60s and early 70s, first laying the groundwork for prog and then taking it into ever jazzier realms. In 2011, key Canterbury musicians looked back at the cult scene they were part of.

The hotchpotch of clued-up teens, curious locals and pissed squaddies crammed into the smoky downstairs bar of the Bear And Key pub on Whitstable High Street on this Friday evening are blissfully unaware that the unceremonious event they’re about to witness will be prove to be a pivotal one in English rock history.

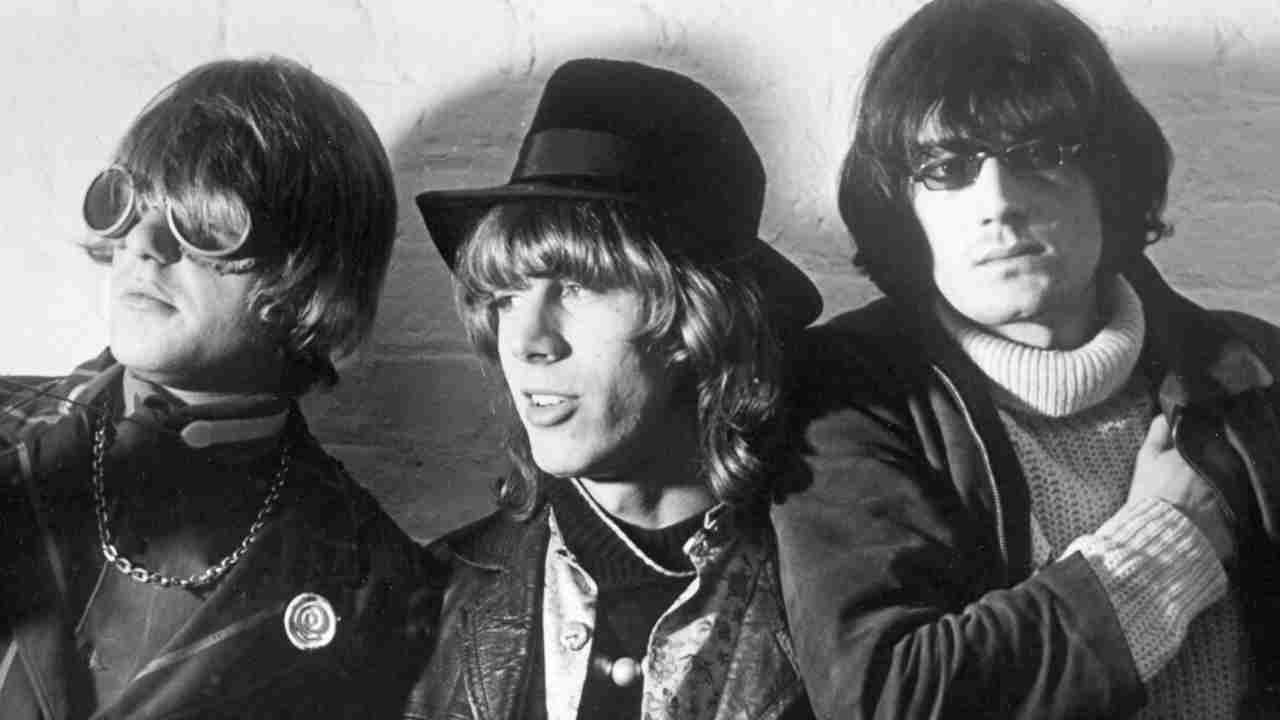

It’s January 15, 1965, and on the pub’s tiny stage the six young men from nearby Canterbury who make up the band called The Wilde Flowers are preparing to make their first public performance. Striking, blond-haired vocalist Kevin Ayers, guitarists Richard Sinclair and Brian Hopper, the latter’s bassist brother Hugh, keyboard player Mike Ratledge and drummer Robert Wyatt may be young, but they possess both a quiet confidence and a fierce musical intellect. Taking the stage at 9pm, dressed in brightly coloured silk shirts – pink, turquoise, yellow, red, blue and olive, all hand-made by the Hoppers’ mum – their flamboyant mix of blues and rock’n’roll covers, together with originals such as Ayers’s She’s Gone, soon win over the disparate audience.

For one audience member in particular, it’s a life-changing event. “I was at the show with my sister Jane,” recalls Pye Hastings, then a 17-year-old student who, within a couple of years, would have joined The Wilde Flowers and subsequently become the linchpin of the band Caravan. “Like all first gigs, it was a bit of shambles, but it was very exciting. It gave me the target I was looking for: I wanted to be in a rock’n’roll band.”

Little did The Wilde Flowers know, as they toasted their success with Coca-Cola on the short trip back to Canterbury, that they had started out on a path which would put this sleepy corner of Kent on the rock map, turning convention on its head in the process.

“Those early gigs were a lot of fun,” Robert Wyatt says today with a grin. “We had that all-for-one mentality you have when you were young. We all knew that we were at the start of something, we just didn’t know what.”

British rock is essentially the sound of the city. From Merseybeat’s Northern reinvention of rhythm and blues to the Midlands’s molten contribution to heavy rock to the spiky belligerence of punk-era London, it has largely derived its creative energy from the streets. But in Canterbury in the late 60s and early 70s a loosely aligned group of like-minded musicians – among them Caravan, Soft Machine, Kevin Ayers, Gong and Hatfield And The North – communed a more meditative tradition. Inspired as much by jazz, folk, Anglican church hymns and modern classical music as by rock’n’roll, this was a scene where the head ruled the heart, musicianship was prized over blind enthusiasm, and the object wasn’t commercial success but the thrill of infinite possibility.

“Creativity and originality were prized above all else,” says Dave Stewart, keyboard player with Egg and Hatfield And The North. “We were into making more adventurous music. No one involved had any concept of having hits or making a commercial record. People wouldn’t have even known what it meant.”

Viewed through the rose-tinted spectacles of history, the Canterbury scene possesses a curious, dream-like aura: a stoned shire of winding cobblestone streets and patchouli-scented head shops where zonked-out hippies on a diet of dope and mung beans created 18-minute song suites with titles like The Dabsong Conshirtoe (Caravan) and shorter, though no less out-there songs such as Lobster In Cleavage Probe (Hatfield And The North).

The thing that bound it all together was Canterbury itself. The cradle of English Christianity and a shrine for religious pilgrims for nearly a millennium, Canterbury echoes with the spirits of Geoffrey Chaucer, Thomas Beckett and Christopher Marlowe. Even today, Kate Middleton lookalikes politely tout boat trips from Kings Bridge (built in 1134) to Greyfriars, a 13th-century Franciscan chapel that lies a gentle punt down the river Stour. It’s easy to forget that London is just 60 miles away up the A2.

“You can hear the music from the Cathedral everywhere you go,” says Richard Sinclair, one of the six boys in The Wilde Flowers who made their debut at the Bear And Key, and later a founder member of both Caravan and Hatfield And The North. “Canterbury is a gentle place. It’s in the middle of the garden of England, and the countryside around is full of gently undulating hills. In a funny way, the music sounds a bit like that too.”

The vibes may have been bucolic, but had the Noise Abatement Society been active in the autumn of 1960 they would have undoubtedly been regular visitors to Wellington House. A rambling Georgian residence in Lydden, 10 miles outside of Canterbury, it was the home of BBC journalist Honor Wyatt, her psychologist husband George Ellidge, and their 15-year-old son Robert. A gifted pianist and painter, the jazz-loving teenager was a budding bohemian with a rebellious streak – he was once caned for signing himself in as ‘Jesus Christ’ on a school trip to Canterbury Cathedral.

The soundtrack of jazz and contemporary classical music that rang through Wellington House was ratcheted up several notches with the arrival of a lodger: a 21-year-old Australian beatnik named Daevid Allen. A long-haired beanpole with a suitcase full of 500 rare jazz albums, Allen took delight in shocking the deeply conservative locals by walking through the town centre with his ‘pet’ – a can of dog food on a long piece of string. Wyatt and Allen immediately hit it off.

Encouraged by Allen, Wyatt took drum lessons from respected jazz player George Neidorf. Soon, he and his equally adventurous schoolfriends Kevin Ayers, Mike Ratledge and Hugh and Brian Hopper began to formulate plans for a band of their own, and by the summer of 1961 Wellington House throbbed nightly with an atonal cacophony of artistic endeavour. The only thing they lacked was a decent guitarist.

The solution came in the shape of Richard Sinclair, an art-school friend of Hugh Hopper with an angelic singing voice, a dry sense of humour and a musical pedigree that ran in the family (his father and grandfather were local musicians). Sinclair was soon enrolled on a crash course in the alternative lifestyle.

“I was only 15 and they were a bit older,” he says. “Robert had long blond hair. It was obvious he wanted to be a pop musician. He had lots of bright ideas and was very good at entertaining people. Kevin Ayers turned up one day with a glamorous girlfriend on his arm and a bottle of Mateus Rosé. It was quite intimidating. The one thing they couldn’t do was play in tune.”

That didn’t stop them christening themselves The Wilde Flowers (“Kevin added the ‘e’ in tribute to Oscar Wilde,” Wyatt says with a grin) and booking their first gig, a few miles away at the Bear And Key in Whitstable.

Julian Frederick Gordon Hastings – Pye to his friends – was a pupil at Pilgrim’s Boarding School in Lydden when he first became aware of the “strange music” emanating from Wellington House. A lanky, ginger-haired teenager, Hastings was the son of a banker and an Indian-born mother whose own father had been a Police Commissioner in India during the days of the Raj. His elder brother, Jimmy, was a respected saxophonist who had played with Brit jazz linchpin Humphrey Lyttelton’s band.

Pye was also a friend of Kevin Ayers, and was swiftly brought into The Wilde Flowers’ circle. A spectator at the band’s first gig, he made the transition from fan to member when he stepped in to help out on guitar at a Battle Of The Bands contest in Margate in May 1965. To everyone’s surprise, the band came out joint winners.

“I loved every minute of it,” says Hastings now. “Life in a band – getting drunk, getting pulled, getting paid. I knew I was on some sort of journey and I didn’t want to get off.”

If Hastings saw The Wilde Flowers as the start of a life in music, for some of his new bandmates it was the springboard for a journey into the unknown. Frustrated by Canterbury’s inherent conservatism and enticed by Allen, Wyatt and Ayers would embark on Kerouac-inspired trips to Paris, Morocco and Ibiza, while other members would come and go, leaving Hastings to lead an ever-changing line-up of The Wilde Flowers.

One new member was Dave Sinclair, cousin of on-off guitarist Richard. A prodigiously talented, self-taught pianist, the unassuming Sinclair was impressed by Hastings. “Pye had a worldly air and an interesting and confident style on guitar,” he recalls today. “His songs were coherent and friendly little ditties.”

By the summer of 1966 The Wilde Flowers had split into two distinct, albeit friendly camps. Inspired by a three-day acid trip in the Balearics, Wyatt, Allen and Ayers had formulated plans for the first avant-garde pop group, which would be christened The Soft Machine (a name inspired by keyboard player Mike Ratledge’s interest in author William Burroughs).

For Hastings, the choice was stark: continue to play a mix of covers and originals in local pubs, or form his own band with remaining Wilde Flowers Dave and Richard Sinclair, and drummer Richard Coughlan. He opted for the latter.

“I took the name Caravan from a Duke Ellington tune me and my brother Jimmy loved,” Pye explains. “It seemed to suggest a caravan of ideas.”

With the members of the nascent Canterbury scene literally doubled overnight, the first half of 1967 saw the two new bands taking very different paths. On the back of a demo sent to Jimi Hendrix’s manager, The Soft Machine relocated to London, and promptly took the capital’s underground scene by storm thanks to a radical approach to live performance.

“The music was played incredibly loud with lots of raucous fuzz organ and brain-searing fuzz bass through 100-watt Marshall stacks,” recalled bassist Hugh Hopper of those early gigs. By contrast, the newly formed Caravan spent the Summer Of Love in less psychedelic fashion, helping to build the Sevenoaks bypass in Kent.

Moving into a shared house in Whitstable in January 1968, Caravan set about fine-tuning their sound. Where The Soft Machine bludgeoned their audience into submission, Caravan opted for a gentler, more jazzy approach, with Dave Sinclair’s Hammond organ their not-so-secret weapon.

“Soft Machine were a big influence on our thinking,” says Richard Sinclair. “They used choral melodies but they also played really loud. It was obviously the way to go.”

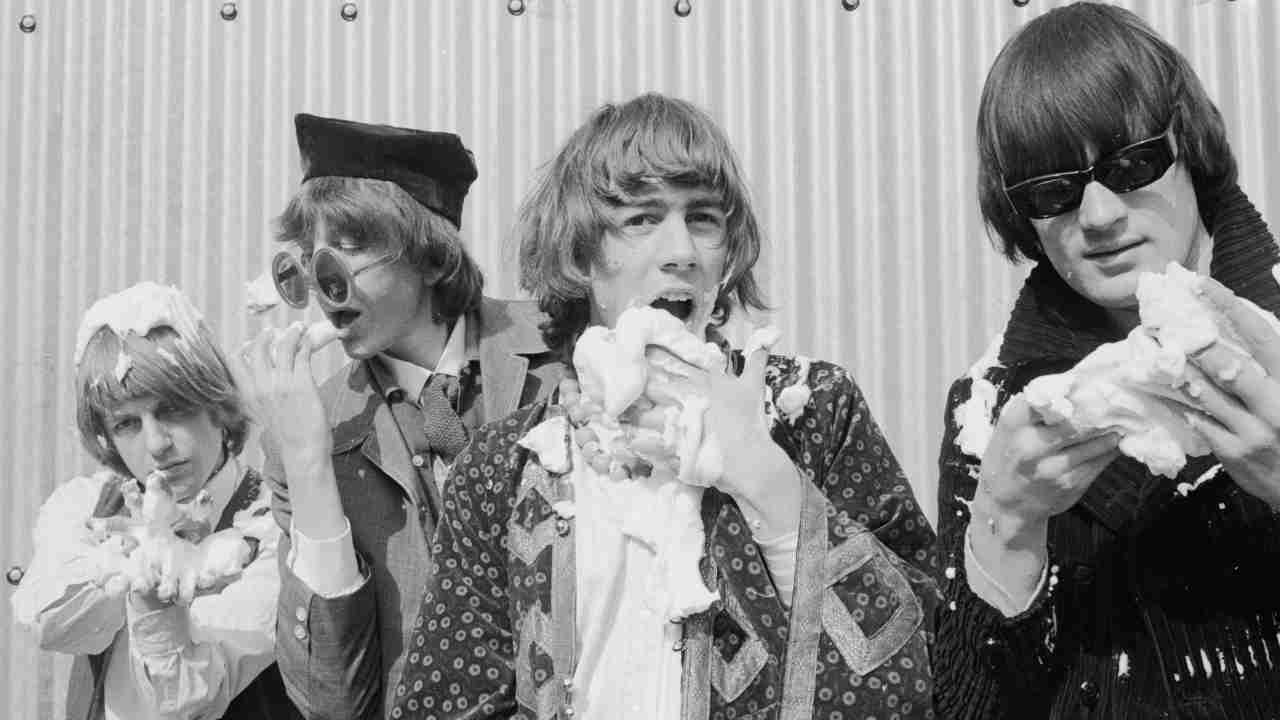

Ironically, despite its location, the house in Whitstable would become the first hub of the emerging Canterbury scene. Attaching mattresses to window frames and pinning fibreglass to the walls, Caravan turned it into their own rehearsal studio-come-sonic laboratory. Things were tight: they played on equipment Soft Machine had lent to them while on tour in the US with Jimi Hendrix, and lived on a diet of Marmite and Weetabix; creative fuel was supplied by repeated listens to Hendrix’s Electric Ladyland, The Rolling Stones’ Their Satanic Majesties Request and John Mayall’s Blues Breakers, and a big stash of dope.

A combination of intensive rehearsals and links with their friends in Soft Machine soon paid off. Following a show at London psychedelic haunt Middle Earth, Caravan signed a deal with MGM/Verve, symbolically inking the deal at the Beehive pub in Canterbury. Untold riches weren’t immediately forthcoming. “We got seven pounds a week,” says Richard Sinclair. “We were hardly any better off than before.”

Money wasn’t Caravan’s only problem. The band were forced to move out of their shared house after complaints about the noise. They decided to camp outside the local church hall in nearby Graveney. When it got too cold, they simply pitched their tents inside, taking them down every Wednesday night for the vicar’s weekly youth club. With no fixed abode, it’s little wonder that Caravan’s debut single, A Place Of My Own, came with a tangible sense of pathos. A superb slice of psychedelic whimsy, it showcased Hastings’s ability to harness the choral tradition of Canterbury to the spirit of the age.

With Soft Machine’s fondness for elaborate time signatures and two-note, Sufi-inspired drones not playing well in the provinces, Caravan became Canterbury’s de facto band. Their self-titled debut album, released in October 1968, pitched its woozy, distinctly English psychedelia on a ley line somewhere between the Garden Of Eden and outer space, while epic, 14-minute closer For Richard – the climax to the band’s shows to this day – highlighted their musical skills and their vaulting ambition.

With radio support from John Peel, Caravan seemed to be on the verge of mainstream success. But then disaster struck when their label, Verve, closed down their UK operation without warning, leaving Caravan homeless once again.

The band had no choice but to hit the road. In October 1969 they played a triumphant show at Belgium’s Actuel Festival, alongside Yes, Genesis and Soft Machine. But at a gig at London’s Marquee club, Hastings was almost electrocuted by some dodgy wiring. The resultant press coverage in the Daily Mirror was scant consolation.

By 1970 the Canterbury scene had broadened out to include several more like-minded bands, including Gong (formed by Daevid Allen after leaving The Soft Machine in 1967), Spirogyra, Dave Stewart’s Egg and Henry Cow. By September 1970, Caravan had signed to Decca’s psychedelic offshoot Deram and released their second album, If I Could Do It Again, I’d Do It All Over You. The suggestive title suggested there was a schoolboy humour behind the wide-eyed star-gazing.

Had it come out 18 months earlier, the album would have effortlessly bridged the gap between psychedelia and prog rock. But, released in the same month as Black Sabbath’s Paranoid, the whimsical cadences of And I Wish I Were Stoned were ill-suited to the proto-metal zeitgeist. While the title track earned them a surprise Top Of The Pops appearance, the album itself failed to chart.

At their new shared house, St Elmo’s, overlooking Canterbury golf course, the band mused on their lack of progress with their friends in Soft Machine and a now solo Kevin Ayers. In this most progressive of scenes, petty rivalries were considered pointless. Instead it was literally tea and sympathy all round.

“We drank a lot of tea in those days,” recalls Richard Sinclair. “Full to the brim. I think Robert Wyatt, Daevid Allen and Pye have all written songs about drinking tea.”

However marginal their presence on the pop scene, the influence of Caravan – and by extension Canterbury – was spreading. At a communal house in St Raduginds St, close to the Cathedral, a hotbed of activity had sprung up around an informal network of musicians and art students. Among them was Essex-born Steve Hillage, a 19-year-old student at Kent university, and a supremely talented guitarist who would later go on to play with Gong and Khan and subsequently forge successful solo and producer (Simple Minds, It Bites, Robyn Hitchcock) careers.

“I was a fan of Caravan before I arrived in Canterbury,” Hillage explains. “I liked the music because it was very melodic, and I liked the way they mixed grooves and melodic chord sequences. As a guitarist it didn’t take long to get involved in the Canterbury music scene.”

Caravan themselves were about to raise the bar even higher. Aware that both Richard and Dave Sinclair had stockpiled songs, Pye Hastings took a back seat for their next album, 1971’s In The Land Of Grey And Pink. Full of Edward Lear-style references to ‘grumbly gremblies’ and advice to the listener not to ‘leave your dad in the rain’, it found the wistful, poppy prog of Richard Sinclair’s Golf Girl butting up against Dave Sinclair’s grandiose 22-minute, seven-part opus Nine Feet Underground, which featured keyboard mastery to rival prog rock rivals Keith Emerson and Rick Wakeman.

Despite high expectations from all involved, the album again failed to make any impression outside of fans of the burgeoning Canterbury scene. For Dave Sinclair it was the final straw. Frustrated by the band’s parlous fiscal state and lack of musical progression, he quit in August 1971.

“I felt I needed a complete break,” he says. “With no support, back-up or advice from management, and with the band seemingly unable to discuss problems among themselves, I decided to leave.”

As far back as The Wilde Flowers, Canterbury’s musicians had a fluid approach to band membership, and by 1971 a total of 12 people had been members of Soft Machine at various times. At the end of that year, Robert Wyatt left the band due to internal tensions and a heavy touring schedule. He had already released a solo album the previous year. His next project was Matching Mole, a collaboration with fellow Canterbury leading light Dave Sinclair.

Back in the Caravan camp, Pye Hastings had brought in keyboard player Steve Miller to take Dave’s place. But tensions were growing between Hastings and Richard Sinclair, evident on the band's next album, 1972’s jazz-orientated Waterloo Lily. When Richard left to join Delivery – later to mutate into Hatfield And The North – in April 1973 it was no surprise.

“The split with Richard was inevitable,” says Hastings. “We were on a collision course. I wanted to play rock music and Richard didn’t.”

With two key members now gone, Caravan were in serious danger of grinding to a halt. But an unlikely upturn in their fortunes came when Hastings chanced upon 22-year-old Geoff Richardson, then living at the communal house on St Radigunds Street. A multi-instrumentalist with the same leftfield sense of humour as Hastings, he was the ideal person to fill the musical void left by the departure of the two Sinclairs.

“I remember the day Pye came round to ask me to join Caravan,” Richardson recalls. “I’d just fed the gerbils and was in the garden shed practicing how to play the saw when this ginger head popped around the door and asked very politely if I would like to join Caravan.”

Before he knew it, Richardson was boarding a plane with the rest of Caravan for an Australian tour with Slade, Status Quo and Lindisfarne.

“My feet never touched the ground,” he says. “That tour was very rock’n’roll. One local airline refused to fly Status Quo because they were misbehaving with stewardesses. And Lindisfarne were a handful too. They destroyed the gym at this very posh hotel in Melbourne single-handedly.”

While wanton excess was never Caravan’s thing (“we were boozing, of course, but we were nice, middle-class boys” says Richardson), playing in front of audiences of 25,000 screaming Slade fans instilled a toughness in their 1973 album For Girls Who Grow Plump In The Night. It also saw the surprise return of Dave Sinclair. Short of cash, having quit both Matching Mole and Hatfield And the North, he returned to the band on a session basis.

“Dave had been unhappy about the songwriting split,“ says Richardson, “so he rejoined the band on a flat fee. As it turned out, he would probably have been better off taking a royalty.”

With Hastings’s pervy lyricism reaching new, Max Miller-ish peaks (notably on The Dog, The Dog, He’s At It Again), …Plump… was the sound of a revved-up Caravan, their finely tuned musical engine apparent in the 10-minute, multi-part finalé L’Auberge Du Sanglier/A Hunting We Shall Go. But Hastings’s schoolboy humour worked against him this time: the punning title and sleeve design featuring a slumbering girl (Hastings had originally wanted a gatefold image of a naked, heavily pregnant woman) caused the album’s release to be delayed after complaints about sexism from Boots and Woolworth.

Still, the response to the new album, together with the acclaim surrounding an orchestral concert at London’s Drury Lane Theatre, brought them to the attention of Miles Copeland, the fast-talking manager of Wishbone Ash and Curved Air. Crucially, he had a reputation for breaking bands in the US.

“With Miles at the helm we felt invincible,” says Hastings. “His strength was in building confidence in his artists, coupled with the American attitude of ‘everything is possible’.”

Copeland’s first move was to send the band on a 50-date, coast-to-coast tour of the US in September 1974, supporting bands including Fleetwood Mac and Fairport Convention.

With the wind in their sails, expectations for the band’s next album were high, with characteristically extravagant 18-minute song-suite The Dabsong Conshirtoe as the piece de resistance. However, plans to call the record Toys In The Attic had to be abandoned at the last minute when the title was nabbed by Aerosmith. Hastings’s substitute? Cunning Stunts.

“It’s the punchline to a joke Richard Coughlan was fond of telling,” Richardson grins. ‘What’s the difference between a policeman’s truncheon and a magicians wand?’ One is for cunning stunts and the other is for stunning cunts.”

Thanks to a Spinal Tap-esque manufacturing mix-up, the album actually charted in Belgium as Stunning Cunts.

“Many years later I watched Spinal Tap at Pye’s house one night,” says Richardson. “We were both pissed. He quietly wept while it was on. It was so accurate. Way too close to the bone.”

In late 1975, Miles Copeland woke up one morning with a burning conviction. The previous evening he had the seen the future of rock in sleazy dump of a pub in Deptford. The band were called Squeeze. Embracing the nascent punk scene at West End club the Roxy, Copeland realised that popular music was about to experience an upheaval not seen since Elvis’s appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show in 1956.

“Miles called a meeting of all his bands,” explains Geoff Richardson. “Wishbone Ash, Curved Air, Renaissance, Caravan and The Climax Blues Band. He told us that he’d seen the future, and it was punk. He dropped everyone on the spot.”

Despite being dumped by their manager, the penny didn’t drop immediately for Caravan. Punk? Copeland had clearly lost his marbles. In their minds, the record-buying public would clearly prefer the good-humoured virtuosity of their new album Blind Dog At St Dunstans.

Caravan soon realised they were wrong. By the summer of 1977, they and their peers – among them Henry Cow and Camel – were as fashionable as bubonic plague. In the eyes of diehard Canterbury scene fans, music was entering its version of the Dark Ages.

“Punk’s ostensible project was to take things back to basics,” says the novelist Jonathan Coe, who named his breakthrough book The Rotters’ Club after Hatfield And The North’s second album. “All it did was make real musicianship unfashionable. A generation of some of the most gifted rock musicians this country had ever produced suddenly had their already precarious livelihoods taken away from them.”

By the mid-80s the Canterbury scene had only one very vocal public fan: Neil Wheedon Watkins Pye, a clinically depressed, vegetarian pacifist with the catchphrase ‘Heavy, man’, and one of the main characters in anarchic BBC sitcom The Young Ones.

“My business manager had heard that Nigel Planer [the actor who played Neil] wanted to do a version of Traffic’s Hole In My Shoe,” recalls Hatfield And The North’s Dave Stewart. “I was a big fan of the Neil character, so I offered to record the demo and it went on to be a big hit. Nigel was a big fan of the Canterbury scene. He told me Steve Hillage was Neil’s favourite artist, which I thought was hilarious as he was an old mate. We even did a version of Caravan’s Golf Girl on Neil’s Heavy Concept Album.”

All of which must have brought a wry smile to the face of Pye Hastings. Following a trio of poorly-performing albums in the late 70s/early 80s (Better By Far, The Album and Back To Front), by 1990 he was working as a labourer to make ends meet. “Believe me it was the best therapy in the world,” he says. “Every blow with a four-pound club hammer was landing on the imaginary head of some poor bugger who I felt had done me wrong.”

While former peers Yes and Genesis took the turning into rock’s superleague, Hastings built up his own specialist plant hire company. Dave Sinclair, meanwhile, opened his own piano shop, Avenue Pianos, in Herne Bay. However, Hastings remains sanguine about Caravan’s failure to hit the heights. “Yes and Genesis are both brilliant bands,” he says. “Unfortunately we became the ‘also rans’. Bad luck or bad management? No. They’re just lucky bastards.”

Steve Hillage is less circumspect. “The bloated pomposity of Yes was one of the things that led to their success in America,” he says now with a hint of local pride. “Caravan never had that objectionable quality.”

For decades, the Canterbury scene remained the preserve of prog connoisseurs – loved by those in the know, but never held in high regard. That began to change in the late 1990s and early 00s with a resurgence of interest the music it produced. While many of its key figures are no longer here – Kevin Ayers, Daevid Allen, Caravan’s Richard Coughlan, Soft Machine’s Hugh Hopper among them – others are still active, among them Caravan and Steve Hillage. Still the ‘Canterbury scene’ tag is viewed with some disdain by certain of its participants.

“Still it pisses me off,” Robert Wyatt says. “It was something a journalist made up in the 70s and it’s stuck. The myth is that we were all arty boys going round having parties and throwing buns at each other. It was much more austere than that. We were living off very little. It’s not strictly accurate, either. Kevin Ayers grew up in Malaya, and Soft Machine were only there for a short time. The only real Canterbury band was Caravan, because they were in The Wilde Flowers and that’s where it all started.”

At his house in Italy, Richard Sinclair affords himself a chuckle at the thought of Robert Wyatt as a Canterbury scene denier: “It’s funny, because back in The Wilde Flowers days Robert would always talk about Canterbury’s roots as an ancient Roman settlement. He would say it was where they built the first amphitheatre, making it the first place to host live concerts in England. Whenever things went wrong he’d say: ‘Blame the Romans.””

As Neil Wheedon Watkins Pye might say: heavy, man.

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 161, July 2011