Francis Rossi is 75 today, and for 59 of those years he's fronted the same band, Status (initially called The Spectres, then Traffic Jam). In 2019 he sat down with Classic Rock to discuss the band in a no-limits interview: the good times, the bad times, the drugs, and his difficult relationship with his band partner, the late Rick Parfitt. This interview has not been published online before.

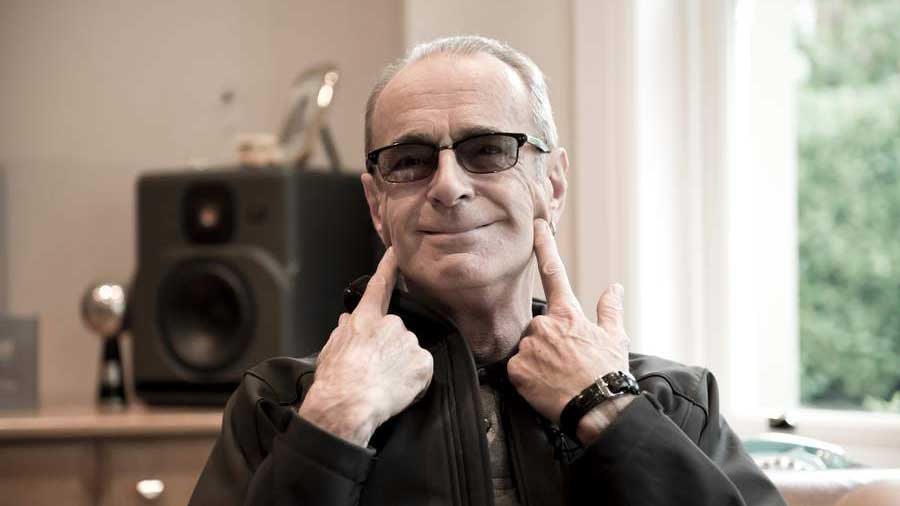

He was raised a Catholic, and has a confession to make. In his home studio, Francis Rossi is recalling the moment in 1967 that, at the age of eighteen, he wrote the song that became Status Quo’s first hit. He rises from his chair beside the mixing console to pick an acoustic guitar from a rack on the wall.

“As Lennon said, there’s nothing new under the sun,” Rossi says with a smirk. After a quick tune up, he strums the intro to Hey Joe, the mythic murder ballad made famous in 1966 when it was a hit single by the Jimi Hendrix Experience. Then, with minimal adjustment, he segues smoothly into Quo’s Pictures Of Matchstick Men, singing in that familiar nasal tone: ‘When I look up to the sky, I see your eyes, a funny kind of yellow.’ He pauses and arches an eyebrow. “Everything,” he says, “has been nicked from somewhere.”

In a conversation with Francis Dominic Nicholas Michael Rossi – a Catholic name if ever there was one – there are many such confessions. Some are funny, some sad. All are told in a manner as unpretentious as the heavy rock’n’roll that made Status Quo one of the most successful British bands of all time.

The place where Rossi lives, in Purley, South London, is just 10 miles from where he was born, in Forest Hill, on May 29, 1949. The large, white-walled house is on a private road, hidden away behind tall gates. The recording studio, in a wood-clad outbuilding set in expansive grounds, is where the last few Quo albums were made with rhythm guitarist Rick Parfitt in the years before his death on Christmas Eve 2016, aged 68.

It was also here that Rossi recorded his latest album, We Talk Too Much, in collaboration with singer Hannah Rickard. And the album’s title is echoed in his forthcoming autobiography, I Talk Too Much, written with Classic Rock’s Mick Wall.

“That’s how I am,” Rossi says. “Some people drink people under the table. I talk people under the table…”

On this dark winter afternoon, dressed for comfort in blue fleece and jeans, and sipping coffee from a Quo-branded mug, Rossi spends the best part of two hours telling the story of his life with an extraordinary degree of candour. At the heart of the story is the band he has fronted for 52 of his 69 years, and in this his long and sometimes difficult relationship with Parfitt.

Rossi has had his share of bad press over the years. He refers to a recent interview for a tabloid newspaper in which he was misquoted about money. “They really took me apart,” he says. But he concedes: “That’s the game, and I allow myself to be part of it.”

Today, no subject is off limits: the rivalries between Quo and other bands, and between himself and Rick Parfitt; the good and bad in doing drugs; the guilt that Rossi feels for putting the band before his children; the bitterness that still lingers between him and his former bandmates John Coghlan and Alan Lancaster; the awful experience of witnessing Parfitt suffering a near-fatal heart attack; the accusations from many Quo fans that Rossi was wrong to keep the band going after Parfitt’s death.

But there is also much that he can laugh about: the good times with Rick, the communal wanking (or ‘a polish’, as he calls it) on early Quo tours; the fun he had with David Bowie and Freddie Mercury; the moment backstage at Live Aid when Rossi concluded that Elvis Costello was, in the bluntest terms, “a c**t”. As Rossi says with a broad smile: “I do have some great stories…”

You turn seventy this year. How does that feel?

My acupuncturist told me: “Oh, you’ve got ages yet.” But she’s thirty. To her, twenty years is a long time. Not to me. Surely I’ll be done by then. I’m just about hanging on now.

Have you changed your lifestyle of late?

No dope-smoking. I gave that up a year ago. It was making me feel so negative. But I stopped and the negativity is gone. I still have one cigarette a day.

So you’re feeling good about life right now?

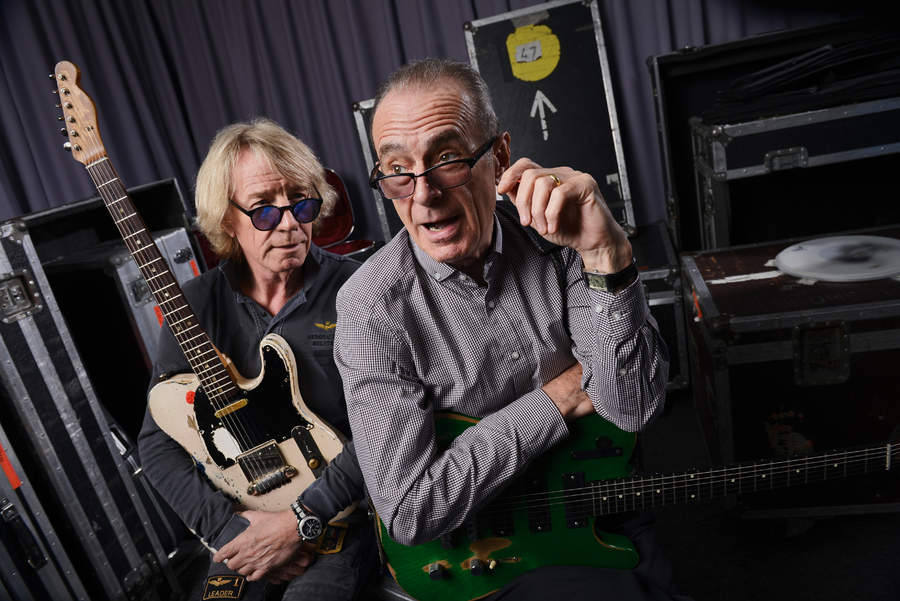

It’s all about enjoying the journey. I thought about this recently when I was trying to write with Andrew [Bown, Status Quo’s keyboard player]. I don’t really want to do another Quo album. I wasn’t looking forward to writing. But we ended up with a new song. And I said to him: “I fucking enjoyed that.” He asked me what I thought of the song. I said: “I don’t care really.” It’s about enjoying the process.

So you’ll carry on making music, with or without Quo?

Yes. It doesn’t have to be Quo.

What drives you? You can’t need the money.

Well I ain’t as fucking stinky rich as people think. I like my lifestyle, but it’s not cheap living here. I just paid out two and a half grand for tree work.

Surely there’s a fair bit coming in?

The band grosses this, and I end up with that. Then I pay forty-five per cent to the tax man.

Did you waste a lot of money in the past?

In the seventies I was paying eighty per cent tax, and the rest you piss away. You take drugs, you buy aeroplanes – well, Rick did – you get divorced, you get ripped off. But I’ve done all right. I’m not poor.

So why keep working?

It has to be ego. I read this thing about successful men, how they’re heavily driven, egotistical, and they only know one thing. And I went: “That’s me.” My first wife bailed. My current wife – I love saying that – she’s allowed me to be obsessed with this.

Is there a sense of guilt in all of this?

I can’t be a good father, because I had eight kids and my career came first. I was at the birth of my first son, in August sixty-seven. I was eighteen then, just before I wrote Matchstick Men. But some of the other births I missed because I was working. That I regret, but only with hindsight. At the time, I wanted my career.

Your father was Italian – his family ran the famous Rossi ice cream parlours – and your mother was Irish. Growing up in South London as the son of immigrants, how did that shape your personality?

A lot of it is front. I was from this strange Italian family, so I pronounced words differently. I was told: “You talk fucking poncey, don’t you, boy?” That strong South London thing was so intimidating. So I would just go into ‘him’. Rick was like that too.

You first met Rick Parfitt at the Butlin’s holiday camp in Minehead in 1965, when Status Quo were playing there. Do you still remember that day well?

It was the twenty-ninth of May. I walked into the camp and within two minutes I’d met Rick. He was in a group with these two birds, twins. They were called The Highlights. He used to camp it up, but in those days everybody did. He watched us sound-check, and told me later that he knew then that he wanted in. So he had some drive.

What was the young Rick like?

He had a great quality inasmuch as you wanted him to like you. The first gig he was with us was at the Welcome Inn in Eltham, and he borrowed the clothes I got married in – green-and-yellow striped blazer, pink shirt and white trousers. But he hadn’t learned the songs, so he unplugged and mimed all night. The others wanted to get rid of him, but I said: “No, I like him too much.”

When Pictures Of Matchstick Men reached No.7 in the UK you were pop stars. Was it all champagne and screaming girls?

Nope. I thought when we have a hit, everything will be fine. But you woke up the following morning and the only difference was you’d sold a few records. And if you thought the struggle of getting there was hard, hanging on to it was even harder.

Pictures Of Matchstick Men is now revered as a classic of the psychedelic era. Were certain ‘influences’ at work when you were writing it?

Drug-wise? No. I don’t even know what the song meant. And I still don’t know.

Really?

It just sounded good at the time. And I never thought that sound would come back. But then all those years later, out come Oasis.

‘Quoasis’, as some put it.

Yeah. Ha ha. Ain’t it new?

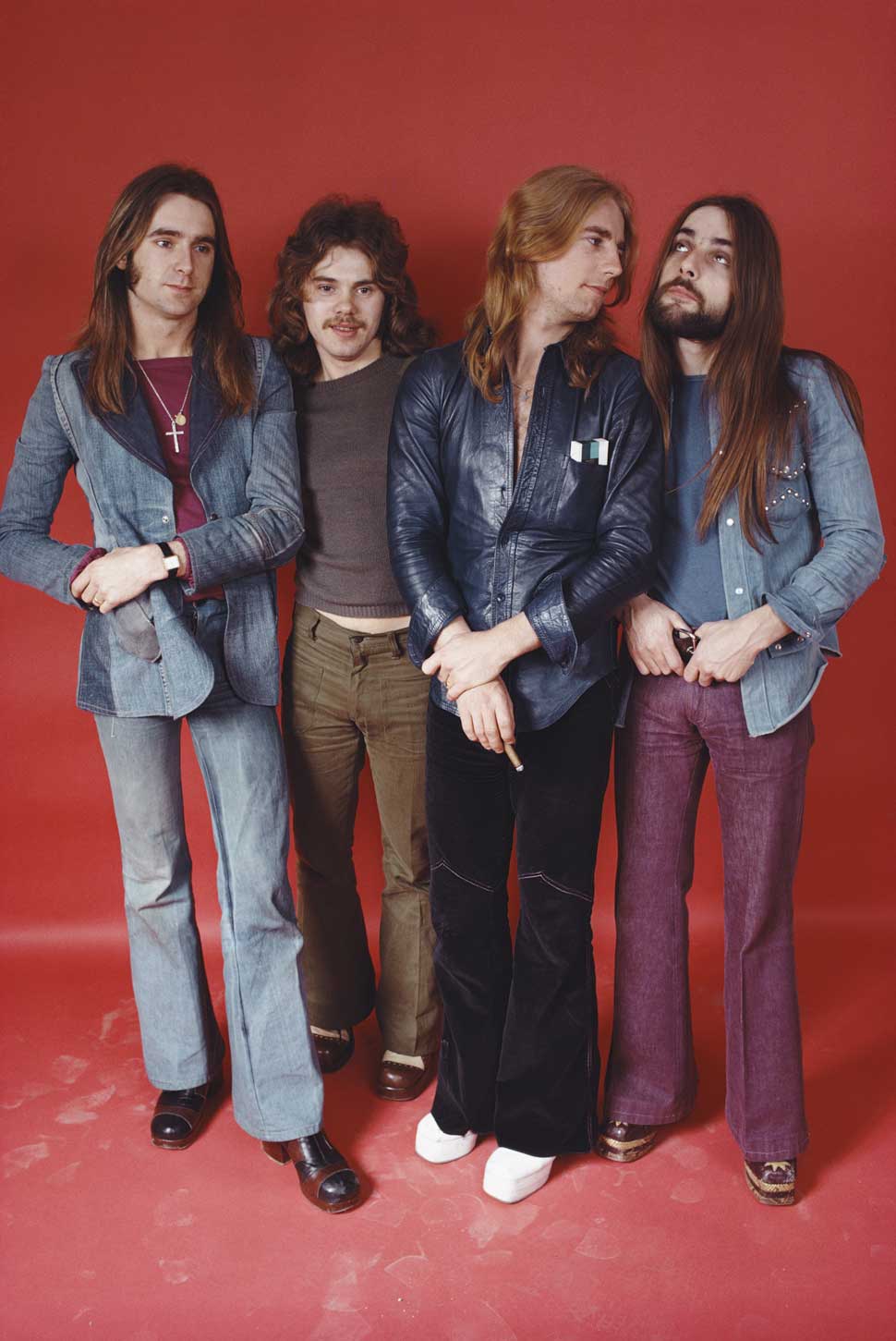

By the turn of the seventies, the ‘real’ Quo had emerged.

That transition that they said we could never do – Quo are goin’ ’eavy!

Famously, you had that eureka moment when you heard The Doors’ Roadhouse Blues.

Rick and I were in Bielefeld, in Germany, at this place called the X Club. We watched this girl and a guy dancing, and the way they moved to Roadhouse Blues was just phenomenal. So that song is where the Quo twelve-bar boogie shuffle came from. That was us: rinky dinky dink…

Most fans view 1972’s Piledriver as the first definitive Quo album. Would you agree?

Yeah. We started to double-track the guitars. That made the sound bigger. The cover was a funny one, though – a cartoon of a gorilla with a bomb. What’s that got to do with a piledriver? Nothing at all. But at the time I thought: “Yeah!” Drugs, eh?

How did you view the other heavy rock bands who were around at that time?

Ooh, Black Sabbath! Fucking man’s stuff, innit? Not that poofy Queen lot!

Did they take this piss out of you too?

Well, everybody thinks they’re better than Status Quo. They do. “Anyone can do that.” Fucking tossers! They liked us being around so they could say they were better than us. But we were like that too. You want to be better than everybody. And we had the most fabulous following.

Who were your famous friends in those days?

We always got on well with the Queen guys, and with Reg.

You mean Elton John?

When I first met him he was Reg. We’re not allowed to call him that any more, apparently. But he was always Reggie to me. And Rick and Rod Stewart were such good muckers, always out getting rat-arsed. That’s one thing I miss about those days. We were all muckers, all happy for each other to be successful.

In the seventies your drugs of choice were speed and weed.

They lie to young people about drugs – how terrible they make you feel. The truth is, drugs make you feel great – at first. I remember when we did Mystery Song [in 1976]. We left Rick in the studio one night, sitting on a stool, playing: da da da, da da da… We came back in the morning and said: ‘You all right?’ He said: ‘I ain’t been home yet!’ Still speeding. Da da da, da da da…

Was cocaine the logical next step for you?

Here’s another lie: cannabis leads to harder drugs. What led me to cocaine was the alcohol. Once you’re full of alcohol you’re Jack the Lad. “Go on, then, give us the coke!” I was frightened of drugs, but I became a coke addict for some time. I get really annoyed when people talk about the ‘rock’n’roll lifestyle’. No, we’re indulged. It’s arsehole behaviour, but it’s allowed because you’re making money for people.

For a long time the band was a tight-knit unit. So tight, in fact, that on early-seventies tours you would get together in a hotel room to watch porn.

That was in Deutschland. There were girls outside the hotel, going: “Shag, Englishmen?” But we were busy inside, having a ‘polish’. I shouldn’t keep telling that story. I’m more ashamed of it the older I get.

What do you think it was that changed your relationship with Rick?

Everything changes when we grow up and we get married and have children. When we’re young and in a band it’s us against the world. Then the money comes in and it’s: “That bloke’s got more than me.” And off it goes. It was around seventy-seven, after Rockin’ All Over The World, that Rick started to push himself forward. He said to me: “I’m fed up with being number two.” I told him: “Don’t do that.” He was my friend, a person I loved, and he was soiling that.

Did he feel the same way about you?

Probably. I was being a c**t and Rick was being a c**t. That’s when he and I began to drift apart. I dare say that’s happened with all of those classic rock partnerships, as it were. And then various people fed into Rick’s ego. He was trying to live this image that people had convinced him was who he should be. With the Rick I loved and knew, there wasn’t much male ego. He had an ego, but it wasn’t macho at all.

On July 13, 1985, at one minute past noon, Quo opened Live Aid with Rockin’ All Over The World. There were 72,000 people inside Wembley Stadium, and close to two billion watching around the world. Did you realise beforehand how big this was going to be?

Oh no. You’ve got to give Bob Geldof his due. He got everybody to do it. When he asked us, I said: “Look, Bob, we’re not getting along, we’re not rehearsed, we’ll sound like a sack of shit.” He said: “It doesn’t matter a fuck what you sound like, you’re the ones!” Subsequently I found out he said the same thing to The Who, to everybody. The funny thing was, everybody was jockeying not to open. But when we felt the vibe coming off that audience, I thought: “Oh, hang on, I get it!” It was the most euphoric gig.

Did you think, as most people did, that Queen stole the show?

They were the donkey’s knob that day. Everyone said: “Jesus, they’re on it.” But they would be, they’d been out touring.

Who were the other artists that you mixed with backstage at Live Aid?

Near the end of the show, I was sitting at a table with Bowie, and as Geldof was trying to get everyone up for the big finale the lights went out and the table collapsed. I did go back up on stage, but I didn’t want to. It was embarrassing. So I stayed as far back as I could. I always got on all right with Bowie, though. That mysterious image he had, that was not the man he was. He was just a nice guy.

Freddie Mercury?

Something I picked up from those straight South London boys: “Them poofs are wimps.” Fucking hell, there’s a mistake. As everyone was decamping out of Live Aid, Freddie bent me over a desk, in a half-nelson, held me down and I couldn’t move. Fuck, he was strong.

Was there anyone you didn’t like?

I remember getting the hump with Declan – Elvis Costello. I said: “Alright?” And he looked at me like: “I can’t talk to you, I’m a proper musician.” C**t. Get over it, son. I’m over it. You’re up your own bottom, aren’t you? Rick and I always said let’s not be like that.

Alan Lancaster left Quo soon after Live Aid. John Coghlan had already departed, in 1981. Then in 2013 you and Rick reunited with them when the classic ‘Frantic Four’ Quo line-up toured again. Quo fans were ecstatic, you less so.

An understatement. I could feel a sense of euphoria in the audience, but it was that classic thing: what can you hear that I can’t? Sometimes the only thing that was in time that I was playing off was Rick’s rhythm. In John and Alan’s defence, they weren’t working like Rick and I worked for so long after they left.

What good came out of the reunion?

Bugger all, other than the fans were satisfied.

Not a healing of relationships?

No. Because it’s now gone back to the way it was before. Alan got very insulting with me one day on the phone, exactly as he used to be. So I cut him off. It’s finished. It seems like I’m cold in that respect, but I’m done.

And John Coghlan?

I’ve got other issues with John, and it’s probably not his fault. On the tour, we tried to use click tracks, and John kept saying the click was putting him out of time. Are you reading that one correctly? It’s the metronome that’s putting you out of time? Hello!

Are you sad about how that turned out?

I was elated to get back with Alan Lancaster. He was the guy I met when I was eleven, and it was great when he stayed with me for a couple of months before the tour. We had a laugh going around South London together, looking at the old places. What we shouldn’t have done is all play together again, because Rick and I had come so much further forward.

Do days go by when you don’t think of Rick?

I knew Rick longer than I knew my parents. I have a strange memory. It’s not way back in the past, it’s there in front of me. So there are times when I can see a picture in my mind: there’s Rick.

Did you ever talk to him about what had gone wrong between you?

Later on he’d say to me: “Why don’t we get on like we used to?” “I don’t know, Rick. Not now. It’s fucking two in the morning.” “Well I want to talk about it now.” “No, Rick. It’ll be drunken talk, we won’t remember in the morning.” I just think they got to him with that “You’ll always be number two” routine. You could sow that seed of doubt with Rick. You can with anybody.

In June 2016, following a Quo gig in Turkey, Rick suffered a heart attack, and you witnessed him being revived. Can you describe what happened?

He was dead. We were all standing there as they dragged him off the bed and he bounced off the floor. They tried every fucking trick in the book, and I thought: “Why are they doing that to him?” It was fucking horrible.

Did anything change between you and him after that?

When I went to see him, as much as his boys said he was fine, no he wasn’t. He was completely different. He was talking to me as though we were back in 1984 or something. I think he realised that he probably wasn’t going to live as long as me because he kept having serious problems with his heart. But that was something we used to joke about – who would die first. Andrew [Bown] used to say that Francis Rossi would die with a joint in his hand and Rick Parfitt would die in a Mandrax factory. It sounds morbid, but that’s how we were. And then, on Christmas Eve, I got the call: “Rick’s dead.”

Had you prepared for this?

We knew Rick was going to die, but the reality of it was such a shock. I heard Rick’s voice in my ear: “See, Frame,” – he always called me Frame – “at least I didn’t die on a show day.” And I laughed. I thought, that would be Rick. He knew if he’d died on a show day we’d have had to cancel. And we’re too ‘show business’ – we don’t cancel.

How has this affected you on a deeper level?

After he died, I was asked: “Did you cry?” No, I didn’t. But I did one night when I was on the tour bus. I played the original version of that song of Rick’s All The Reasons [from the Piledriver album]. Rick wrote lovely little songs. All The Reasons is fucking wonderful. And just for a second I thought: “There he is” – there’s the bloke I loved.

Did you think, in the days after Rick’s death that Quo was finished without him?

I wasn’t necessarily going to carry on. I didn’t know what I was going to do.

Would he have kept the band going if you’d died first?

Yes. We both knew that. One of the things that kept Quo going in the early years was: “Fucking chancers, the same old shit, they won’t last long.” Oh really? We were going to fight. The same when we split with Coghlan and Lancaster: “No good without those two.” Really?

The same is being said now.

I’ve read the comments: “Oh, he should fucking stop it now. He’ll be no good without Rick.” Okay, maybe those people are right. But what they’ve done is make me go: “I’ll show you.” I thank those people that said I can’t do it without Rick, just as Rick and I thanked all the people that said we couldn’t do it without Lancaster and Coghlan. Because firstly, we did, and secondly, probably I’m going to. And I have done already. With some of the gigs we’ve played in the last two years, I’ve gone: “Fuck, it’s better than sex.” In the final analysis, it’s still Status Quo.

Are Quo underrated?

I can’t say that. And I really don’t know. Some of it’s fairly simple. I listen to some of our albums and think: “Jeez, that’s dreadful.” I listen to other albums and think: “Fuck me, that’s a magical moment.” Some people see Status Quo as sacred. I don’t quite see it that way. Like any other band, it had some fantastic moments and some shit. The only band I never saw do any shit was The Beatles, and maybe the Eagles.

There are so many classic Quo songs: Caroline, Down Down, Rain… Which are you proudest of?

There are songs you’ve written over the years that you want people to love, and there’s a handful where I don’t give a shit whether you like them or not, because I love them so much. Marguerita Time is one. All We Really Wanna Do [from Rock ’Til You Drop, 1991] is another, and Tongue Tied [from In Search Of The Fourth Chord, 2007].

Do you think you’ll know when it’s time to knock it on the head?

There’s something in me – and I don’t mean this morbidly – that thinks why can’t I just sit around and wait for death? Why not just potter about and grow old gracefully? But then I get enthused. I’m looking forward to getting back and playing with the guys again in the summer.

And before that, your autobiography.

I won’t read it. Not for a year, at least. I’m sure there are things in the book that I shouldn’t say.

Looking back, do you have any regrets?

I don’t know. I’ve just done the best I can. I’ve been selfish, as we all are. We’re human.

And do you think about how you would like to be perceived?

No. That’s too much ego. I’m just a basic dickhead, and a bit insecure. I hope that people would think I was a reasonable bloke, not a nasty fucker. That’s about all I could ask for.

Status Quo's 2024 tour is now underway. For dates and tickets, visit the Status Quo website. The new live album Official Archive Series Vol. 3 - Live At Westonbirt Arboretum is released on July 12. This interview originally appeared in Classic Rock 260, published in February 2019.