On June 2, NASA revealed it is funding two landmark science projects under the umbrella of its ambitious Artemis Program. Artemis aims to send humans back to the Moon by the mid-2020s and, eventually, humans to Mars a couple of decades later. But to get there, NASA and its science partners must answer several fundamental questions about the Moon, including these two:

- What’s going on in the Moon’s interior?

- How can humans survive the harsh space environment?

The new experiments could help answer both of these questions. One experiment will probe the mysteries of lunar geology — particularly, the ancient volcanic activity that shaped the riven and pock-marked orb we see today. The other experiment will test how the Moon’s gravity and radiation affect living cells — crucial health information to enable humans to live and work safely on the Moon for extended periods of time.

Both of these experiments, which will be shot into space by commercial launch companies, promise to deliver data that will be crucial to meeting Artemis’s goal of establishing a lunar habitat for humans by 2030. But beyond that, the information NASA and the project scientists glean can also help design future crewed lunar missions — and perhaps even crewed missions further afield in space.

HORIZONS is a newsletter on the innovations and ideas of today that will shape the world of tomorrow. This is an adapted version of the June 9 edition. Forecast the future by signing up for free.

The experiments are part of NASA’s Payloads and Research Investigations on the Surface of the Moon (PRISM) initiative, which invites outside organizations and companies to pitch NASA ideas and tech to take to the Moon. In total, the program will award up to $2.6 billion worth of contracts split up between each selected experiment.

Here’s what we know about each project so far:

Living with lunar radiation

The Lunar Explorer Instrument for space biology Applications (aka LEIA, as in princess) is a rather unglamorous and small gadget filled with sensors and live yeast. The research team plans to send LEIA via a CubeSat (also not glamorous) all the way down to the surface of the Moon. There, it will monitor how radiation and lunar gravity affect the yeast’s cells over an extended period of time.

This experiment replicates a fundamental approach to seeing how different environments affect a living organism’s health, ability to reproduce, and evolution that is commonly used in Earth’s labs. For life on the Moon, testing a very simple model lifeform like this will provide crucial observations to enable more permanent human dwellings.

Perhaps the biggest challenge of living in space, including on the Moon, would be that humans will have to endure continuous exposure to radiation at levels not experienced naturally on Earth. Radiation exposure, as we all know, can have significant long-term effects on health.

“Currently, you would reach the maximum tolerated radiation exposure just on the trip to Mars.”

“We really know so little about the long-term effects of chronic medium-dose radiation,” says Corey Nislow, a molecular biologist at the University of British Columbia. Nislow is not involved with the LEIA experiment, but his team has a similar yeast-based radiation monitoring project that will launch to space aboard Artemis I in the latter half of 2022.

Yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) is a common model organism for studying DNA damage in humans. That's because, at the most basic molecular level, yeast cell biology is remarkably similar to human cell biology.

“You can probably make a list of ten subcategories of DNA repair, and all of them are conserved between yeast and human cells,” says Nislow.

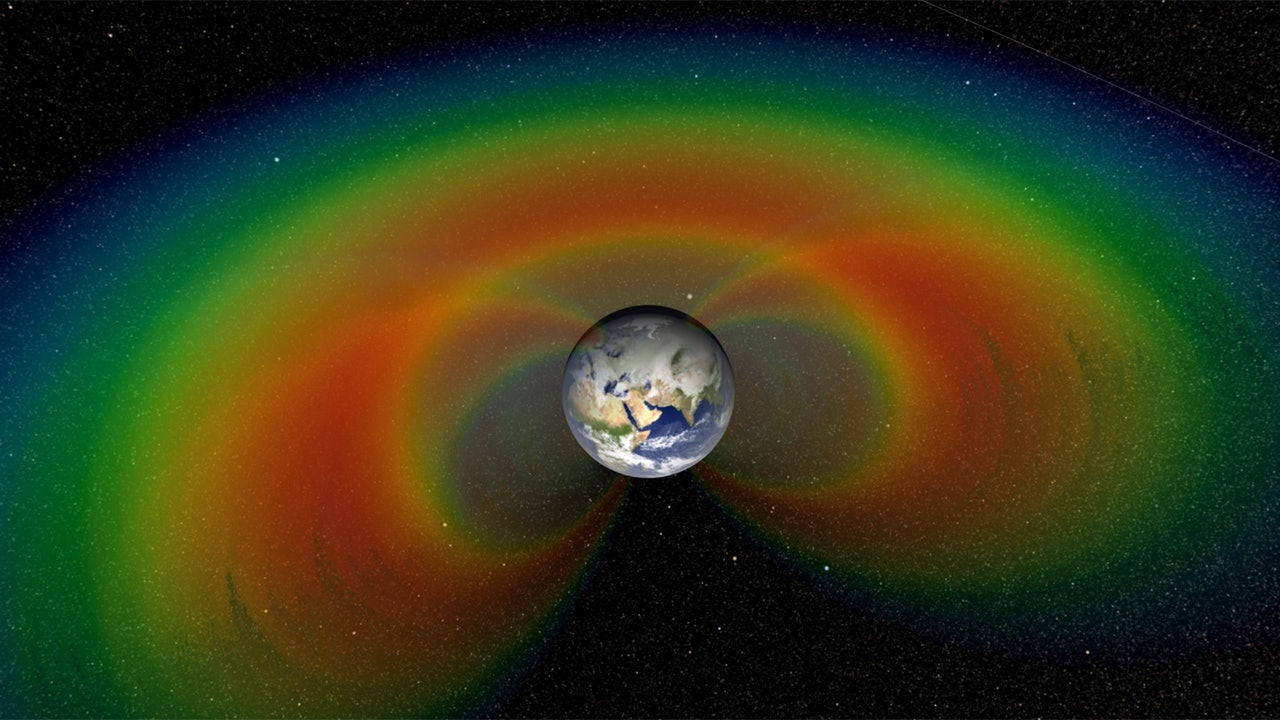

We know that radiation in space is bad news: It hits DNA like a wrecking ball that sizzles skin, impairs motor functions, and even causes cancer. On Earth, the most dangerous doses of radiation from space are blocked by our planet's atmosphere and magnetic field before they can reach the surface. The Moon, like Mars, has very little atmosphere to shield it from harmful solar winds and cosmic rays. Researchers aren’t completely sure how Moon-related doses of radiation will affect our DNA.

The yeast cells aboard LEIA and experiments like Nislow’s will give scientists a better idea of which genes are most vulnerable to radiation damage. This, in turn, will help them develop effective drug treatments to minimize its effects on human astronauts over a prolonged period — an absolutely crucial step toward Artemis's long-term goal of getting to Mars.

“Currently, you would reach the maximum tolerated radiation exposure just on the trip to Mars,” Nislow says.

“We need to get our brains wrapped around the potential damage we’re facing.”

Solving Moon mysteries

The Lunar Vulkan Imaging and Spectroscopy Explorer (or Lunar-VISE, for short) is a two-part mission consisting of a stationary lander equipped with a camera and a rover designed to study the Moon’s geology.

“Something interesting is going on in the interior that we don’t fundamentally understand.”

“Most of the volcanic activity on the Moon happened billions of years ago,” Kerri Donaldson Hanna, a planetary geologist at the University of Central Florida and lead researcher on the project, tells Inverse.

“But there is evidence in a couple of locations on the surface that suggest that there could have been volcanic activity maybe a billion years ago.” In cosmic terms, fairly recent.

Lunar-VISE promises to explore one of these weird lunar locations for the first time: The Gruithuisen Domes. These bubble-like features — named for German astronomer Franz von Gruithuisen — are a bit of a Moon mystery. They closely resemble domes that form on Earth when thick, viscous magma bubbles up from between two seismic plates and is quickly doused by lots of liquid water. But the Moon is pretty much bone-dry and geologically dead, so nobody’s sure how the Gruithuisen Domes got there.

“That tells us that something interesting is going on in the interior that we don’t fundamentally understand,” Donaldson Hanna says.

Lunar-VISE’s mobile rover will roam around the top of one of the domes for about ten Earth days (equivalent to one lunar day), analyzing dust samples as it goes. The composition of the Moon’s dirt should give scientists a better picture of how the domes formed, including how old they are and whether they were the product of some exotic type of lava.

On the horizon…

Both Lunar-VISE and LEIA will be delivered to the Moon via NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) partnership, which currently consists of 14 private spaceflight companies, including SpaceX, Blue Origin, and Lockheed Martin Space.

The payloads are supposed to leave Earth sometime in 2026, but it is too early to say what spaceflight company will take them to their new lunar home. The timeline is also a small reminder of how far we are from settling humans off-Earth. Nislow’s experiment has already been held back by delays to the Artemis I launch, which may have a knock-on effect on future launches.

In the meantime, the Lunar-VISE and LEIA teams are prepping to make sure their instruments pass weight, size, and cost muster for launch day.

“In the next month or so our team will start working with NASA to define what those requirements are,” says Donaldson Hanna.

“We’re certainly excited to start doing all the fun stuff,” she adds.

HORIZONS is a newsletter on the innovations and ideas of today that will shape the world of tomorrow. This is an adapted version of the June 9 edition. Forecast the future by signing up for free.