The modern history of Western Europe is defined by opposition. Europe is presented as a beacon of civilisation facing down the barbarous masses that populated the rest of the world, and one of the customs that, for centuries, stood between Europeans and the rest of the world was cannibalism.

While it is often portrayed as one of the cruellest and most horrifying practices imaginable, my recent research shows that humans ingested other humans’ body parts in Western Europe, both in prehistoric times and throughout the centuries that followed.

The reasons for this practice ranged from nutritional needs to the religious and healing practices documented in various periods. In the Middle Ages, there are references to how cannibalism was recurrent in periods of famine, war, unrest and other testing times for social coexistence. However, there was also a form of cannibalism that considered some parts of the human body to serve a medicinal purpose.

An eternal taboo

For centuries, the dismembered human body was seen as just another material to be used in all manner of remedies and cures.

Between the end of Roman antiquity and the beginning of the Middle Ages, laws appeared in both the Codex Theosianus and the Visigothic Code referring to the prohibition of violating graves or tombs. It was also forbidden to desecrate them in order to extract any kind of remedy derived from the human body, such as blood.

Therefore, from the 7th century onwards, there were already laws inherited from earlier times that regulated or punished seeing tombs and human remains as a source of curative materials.

The Roman and Visigothic prohibitions were not the only ones in Europe, and over time, other normative texts appeared. These laws only existed, and proliferated, because the practice itself persisted.

Christian penitentials

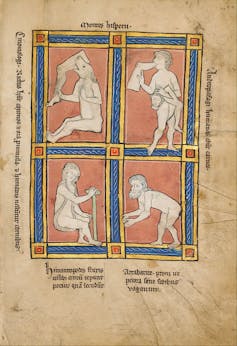

With the establishment of Christianity came the Handbooks of Penance: books or sets of rules listing sins and their corresponding penances. These reflected early medieval ecclesiastical concerns in regulating society – what was right and wrong, what could and could not be done – in terms of both violence and sexuality.

For instance, the Hibernian Canons forbade drinking blood or urine, under penalty of seven years on bread and water under the supervision of a bishop. At the end of the 7th century, other penitentials determined the impurity of animals that had fed on human flesh or blood, and forbade eating them.

The most famous penitential of its time, that of Theodore of Tarsus, Archbishop of Canterbury, makes two mentions of the prohibition of ingesting blood or semen, addressed in particular to women who drank the blood of their husbands for its curative properties. Once again, we see that these products are cited as remedies, just as in the Visigothic Code.

Leer más: Written accounts reveal how sexual assault claims were dealt with in the middle ages

This prohibition is repeated in the penitential of the Monte Cassino monastery. Likewise in Spanish penitentials, the ingestion of semen, or its addition to food, is again punished. The prohibitions affected women in particular and referred to the power they could obtain from male blood or menstrual blood, due to its therapeutic or magical character.

Prohibiting such practices implied that there was a reality that needed to be regulated and controlled.

Religious cannibalism?

From the beginning of Christianity, the ambiguity of its own rituals had led to misunderstandings, such as its practitioners being regarded as cannibals who ingested human sacrifices in honour of their God. In time, some Christians would come to direct this accusation against the Jews in medieval Europe. Allegations of cruelty were also directed at other ‘heretics’ such as the Cataphyrgians, whose eucharist supposedly consisted of mixing children’s blood with flour.

As local saints became more prominent, their miraculous character, as well as access to their burial sites, meant that their bodies were also used for cures and remedies after their deaths.

However, in contrast to other practices that were totally forbidden, contact cannibalism – the ingestion of products that had merely touched the body of the saint or their relics – was permitted. Oils that had passed through the tomb, along with water and even dust and stones from holy burial sites, were ingested in order to seek the healing and the miraculous effects of these “fragments of eternity”. There was thus a shift from consuming the dead (thanatophagy) to consuming the sacred (hagiophagy).

Emperor Constantine’s bath of blood

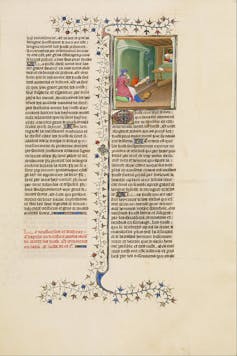

One story that demonstrates the attempts by Christian literature to put a stop to these cruel, supposedly pagan practices is the legend of Pope Saint Sylvester I and the curing of Emperor Constantine’s leprosy. The tale spread across Europe, not only through oral narratives recounting the miracles of the saint’s life, but also in painting and sculpture.

According to the story, Emperor Constantine suffered terribly from leprosy. On his doctors’ recommendation, he decided to bathe in blood, which would be obtained by killing thousands of children. However, when Constantine was on his way to sacrifice the children, Saint Sylvester and the children’s mothers managed to persuade him to abandon the cure and be baptised instead, which miraculously cured his illness.

The story highlights pagan beliefs as cruel and lacking in respect for the human body, and is intended to convey the power of Christian faith in opposition to the vile superstitions that preceded it. From its possible Italian source, the legend travelled throughout Europe, and reached as far as the tenth-century monastic writings of northern Castile.

19th century cannibals

In the Modern Age, and even in the 19th century, several dictionaries of materials – such as José Oriol Ronquillo’s 1855 publication, which was in turn taken from another French dictionary from 1759 – still mentioned parts of the human body (fat, blood and urine) as having curative properties. These beliefs are closely linked to romantic literature, with its array of vampires, werewolves and other human-esque creatures hungry for flesh and blood.

However, long before the 1800s, and even before the colonisation of America or Africa, cannibalism was a key part of the cultural struggle between supposed pagan barbarism and Christianity. Christianity, however, did not completely abandon the practice, but rather refined it, seeking in contact with relics, or even in their ingestion, a way to both have the cure and eat it.

Abel de Lorenzo Rodríguez no recibe salario, ni ejerce labores de consultoría, ni posee acciones, ni recibe financiación de ninguna compañía u organización que pueda obtener beneficio de este artículo, y ha declarado carecer de vínculos relevantes más allá del cargo académico citado.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.