Given we’ve triggered multiple crises in the natural world it’s time to talk about overpopulation, Jack Santa Barbara writes

Opinion: November 2022 recorded the largest human population ever, 8 billion and counting. Comments from the United Nations and other sources have generally been celebratory.

At the same time Elon Musk and others have warned that the declining fertility rate is a grave threat to humanity. These two opposing trends (population growth and declining fertility) have been discussed from the perspectives of demographics, the impacts on pensions and health care, as well as climate, migration, economic productivity, and geopolitical power.

Generally missing from these discussions is ecological sustainability perspective. Population dynamics of various species is something ecologists have studied for decades. Many species, including humans, tend to grow slowly, and have few offspring that they raise for many years. Individuals in such species live longer and their populations rarely expand rapidly.

Species in this category generally live in a stable environment and their populations expand to a limit their environment can support. If they temporarily use more resources than their environment can continue to provide, populations decline until they re-balance with their environment.

Many indigenous human populations established a balance with their environment only after trial and error, with population losses due to over-harvesting prey species, for example.

Humans, elephants, giraffes, whales, and many other species reflect this slow growth, stability pattern.

There are other species that expand rapidly when their environment changes in some way that gives them an advantage. Insects, rabbits and mice are species with boom/bust cycles reflecting changes in their environments. Fires, floods, droughts, crop cycles and beech masts, are examples of environmental changes that lead to these dramatic changes in population levels.

The pattern that human population dynamics follow relies on fairly stable environments, which is why the human population was generally stable, or grew very slowly over millennia.

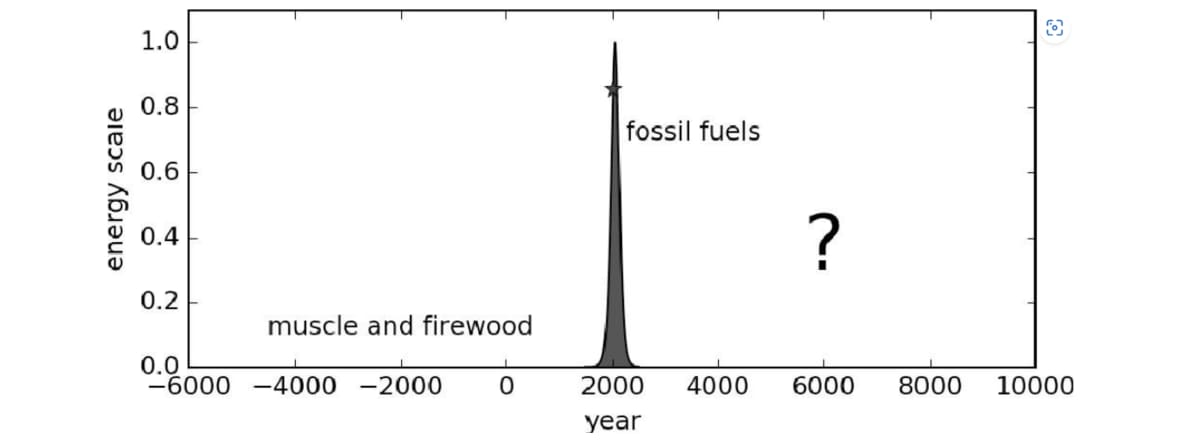

But the human environment changed dramatically only a few generations ago when we started using fossil fuels in earnest.

Fossil fuels provided humanity with an unprecedented energy pulse that allowed the creation of our modern global civilisation (Figure 1).

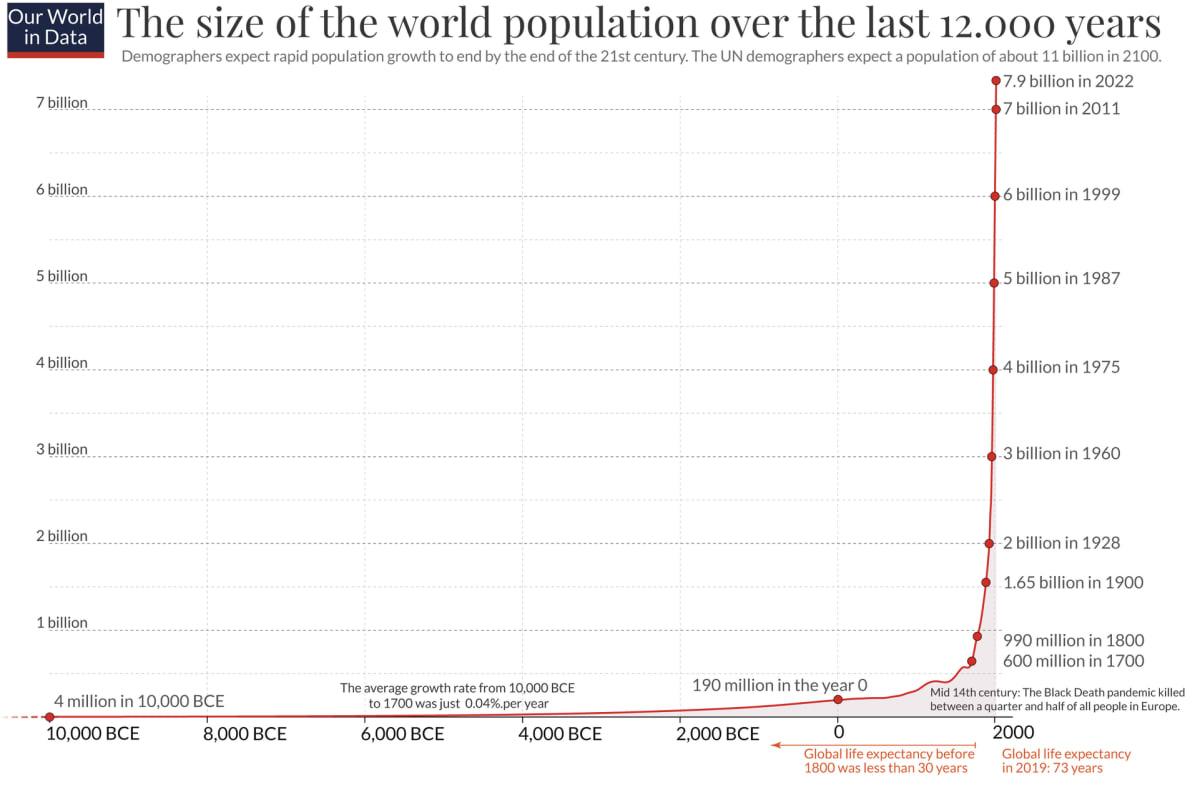

This unique energy pulse not only allowed the development of complex human societies, but it also allowed for a dramatic increase in the human population (Figure 2).

Ecology tells us that successful species are ones that live within their environment’s carrying capacity.

This is the capacity of the environment to both provide essential resources and assimilate wastes for a given population.

This is a visualisation from OurWorldinData.org. Licensed under CC-BY-SA by the author Max Roser

For a given carrying capacity there must be a balance between population numbers and per capita consumption, or throughput. If a population expands, then throughput per capita must decline for the species to remain ecologically sustainable at carrying capacity. Alternatively, the population must decline to regain a balance with the environment. Not tragic for insects. Not so nice for humans.

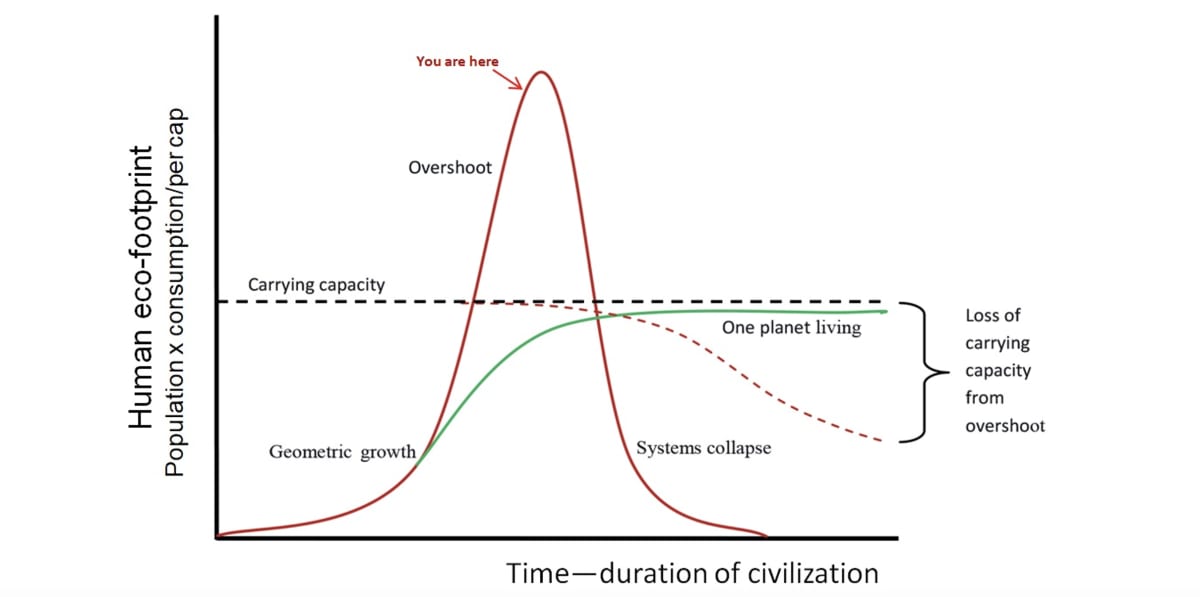

The human species is no exception to this basic ecological dynamic. Our widespread use of fossil fuels has allowed unprecedented and unusual expansions of both per capita consumption, and population, at the same time. These twin, simultaneous expansions are currently pushing us beyond the limits of our carrying capacity into what ecologists call overshoot. Overshoot is the boom part of the boom/bust cycle.

Unfortunately, the empirical evidence indicates humanity is currently in significant ecological overshoot, roughly double beyond our carrying capacity (Figure 3).

On an annual basis we currently use almost twice as much natural resources as natural systems can produce, and create more waste than nature can safely absorb. This is possible because of the great store of renewable resources that nature has accumulated and organised into functioning ecosystems over the millennia.

But over-consuming these stored resources, or natural capital, is like eating into our savings rather than living off the interest. At some level the capital is diminished to the point where the annual interest is minimal and insufficient to support us. When that happens we eat into the capital, which then diminishes all the faster.

By diminishing natural systems we reduce the abundance we have available to use in the future. At the same time we also disrupt many services those natural systems provide for humans and other species (such as climate stability, biodiversity richness, and the capacity of nature to safely absorb our wastes). The extent of our disruption of the biosphere risks its collapse.

So what does all this ecology have to do with the human population reaching 8 billion?

The ecological perspective tells us that our growing per capita consumption of natures’ resources, combined with a growing population doing the consuming, is placing us on a collapse trajectory. It is this combination that is putting too much pressure on natural systems, resulting in many of the major challenges we currently face – climate change, biodiversity loss and widespread pollution.

Urgent calls for reversing this situation are being made from many sources.

The dilemma we face is that we do not seem prepared to reduce either our per capita consumption, or our population size, to return to carrying capacity. In reality, large reductions in both consumption and population are likely needed given just how much we are already exceeding carrying capacity.

The current rate of declining fertility alone will not achieve sustainable levels of consumption fast enough because our ecological overshoot is so large, and worsening rapidly. Gradualism is not going to get us where we need to be. Government programmes to increase birth rates make the global challenge worse.

There are many initiatives to reduce our ecological footprint by developing “clean technologies,” such as renewable energy devices and developing a circular economy. While these initiatives are able to make a contribution, the magnitude of change needed greatly exceeds what they are likely to accomplish.

This leaves us with facing the population issue. A wide range of religious, national, feminist, patriarchal, racial, political, and economic sensitivities make a dialogue about population levels difficult. Nonetheless, population size is a major issue (in conjunction with per capita consumption) with respect to many of the existential threats we now face. Understanding the role of population size can contribute to policies and actions to deal with these very real threats.

A key fact regarding population is that roughly half of all global pregnancies are unintended, and much more than half of these end in abortion. This implies that at least a quarter of all pregnancies worldwide are both unintended and unwanted.

There are, of course, large regional differences in these figures, with very different implications for regional carrying capacity. A further complication is the large differences in per capita consumption across regions.

Providing more women, especially young women, with the means to control their fertility, would be a way of reducing the negative impacts of overshoot we now experience. Education in general, and especially education for women about reproductive rights, along with the availability of appropriate contraception, are proven means of increasing self-control of fertility.

Education about population dynamics would also be important so people can make informed decisions about their fertility.

The evidence regarding unintended and unwanted pregnancies indicates there is much more that can be done to increase women’s control of their own bodies. Policies and programmes that support increased agency for women have proven their effectiveness, but need to be more widespread.

And of course, ensuring basic needs are met also leads to voluntary reductions in birth rates.

Managing their own fertility is important for women in both developed and developing nations, from an ecological overshoot perspective. Developed countries have higher levels of consumption, so fewer births make a greater global contribution to reducing overshoot. This allows for necessary consumption to increase in poor countries without making overshoot worse.

In developing countries with lower levels of consumption, fewer unintended and unwanted births means that per capita consumption can increase more with fewer people consuming.

The productive capacities of ecosystems, along with their waste assimilative capacities, are relatively fixed in terms of what they can sustainably provide each year. So it is a matter of balancing consumption and population to ensure we operate within carrying capacity.

There are a variety of ways of achieving this balance, but we currently don’t pay much attention to either carrying capacity, or what influences it – consumption and population. This is one of those important but difficult conversations we need to have with each other, both within and across nations.

We are unlikely to satisfactorily deal with any of the existential environmental or social threats we face until we do.