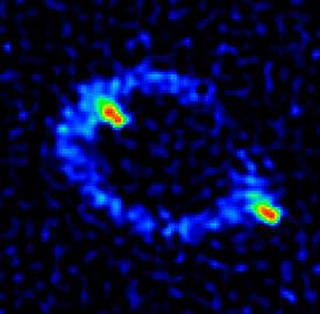

Gravity plays tricks on our telescopes. Take a Hubble Space Telescope image released by the European Space Agency on August 9, 2021. At the center of the image sits a ring of light punctuated by four bright spots, with two more diffuse spots glowing in the middle. This is an Einstein Ring, and its looks are deceiving.

The four bright spots are actually the same object — a quasar — whose light is magnified and multiplied by the gravity of the two galaxies at the center. (In fact, Hubble’s data suggests there is a fifth image of the quasar in the middle of the ring that can’t be seen by the naked eye.) The ring is light from all the stars in the quasar’s home galaxy, smeared out by the same illusion: A phenomenon known as gravitational lensing.

On his 143rd birthday, Inverse celebrates the world’s most iconic physicist — and interrogates the myth of his genius. Welcome to Einstein Week.

Gravitational lensing is a key predictor of general relativity, and, in a twist that Einstein would no doubt appreciate, astronomers now use the rings that bear his name to probe the theory that seems to explain its very existence.

The Einstein Connection

In a 1936 letter to Science, Einstein predicted that the gravity from one star would warp the light of a star directly behind it into a ring.

“Of course, there is no hope of observing this phenomenon directly,” Einstein writes.

Little did he know that we would one day have telescopes powerful enough to image distant galaxies.

“[Einstein] had a sense of the natural sublime.”

The first known image of an Einstein ring was captured in 1987 at the Very Large Array radio observatory in New Mexico. A little over a decade later, Hubble found the first complete one. Since then astronomers have found many more of Einstein Rings including this one, which Tommaso Treu’s group in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Californa, Los Angeles, produced with the Hubble.

“I think he would love it,” says Treu of Einstein.

”I think he had a sense of the natural sublime. He had a sense of the beauty of the natural world, and so I think he would love just the pure beauty of these images, but also the fact that it’s so comprehensible, the fact that we can make a model of the universe that describes everything that happens to these photons over billions of years.”

Einstein rings and general relativity

It’s that very model (the standard model of cosmology, which includes general relativity) that Treu’s group is using Einstein Rings to explore. The rings themselves may be the perfect dark matter detectors.

“My take is that since we only know that dark matter and dark energy interact gravitationally, we should use gravity to learn about them,” he explains.

Treu says that dark matter if it exists, might alter the appearance of the ring of smeared out starlight in the same way that scratches on a magnifying glass distort an image. Depending on the distortion, scientists might learn some of the properties of dark matter.

“There are hundreds of theories about what dark matter could be,” says Treu.

“With these lenses, we can rule out some of these ideas, and, if we are lucky, we can pick one that works better than others. If nature helps us, we may be able to find out which one it is.”

“General relativity could be wrong.”

Einstein rings that include quasars and other dynamic objects like supernovae provide a different method for investigating the so-called “Hubble tension,” which arises because different methods for measuring the expansion rate of the universe give different answers when general relativity is used to model them.

“Of course,” says Treu, “there’s always the alternative. It is that general relativity could be wrong.”

The Hubble tension is only one piece of evidence that the standard model of cosmology might not describe the whole picture, says Alessandra Silvestri. Silvestri is a theoretical cosmologist at Leiden University in the Netherlands.

A more mysterious problem is that the expansion of the universe is accelerating, which requires dark energy to counteract the force of gravity.

“The discovery of cosmic acceleration has given an impressive boost to the exploration of alternatives to general relativity,” Silvestri tells Inverse.

“Indeed, among the open questions (dark matter, inflation, and cosmic acceleration), it is the one that really makes us question whether we need to go somehow beyond general relativity in our description of gravity on large, cosmological scales.”

Treu is skeptical that general relativity will eventually be proven wrong.

“There’s so much evidence that general relativity works, and there’s so little alternative,” he says.

“I think the easiest solution is still that there are particles that we don’t know about. But in the end, we have to be humble, and nature gets to decide. It’s not our call what the right answer is, so we'll have to keep trying.”

On his 143rd birthday, Inverse celebrates the world’s most iconic physicist — and interrogates the myth of his genius. Welcome to Einstein Week.