In February 2022, a twenty-one-year-old Ojibwe and Métis woman named Christine Paquette was job-hunting online. She clicked on a posting for an entry-level position in customer service at CIBC. The call for applications, which was targeted to self-identified Indigenous candidates, seemed typical at first. But then came strange questions: “Do you have a favourite Indigenous story and/or tradition?” The posting also invited applicants to submit a video cover letter and suggested they “dress in traditional regalia or bring in back-up dancers!”

Paquette was baffled. Her mother’s family is from Pinaymootang First Nation in Treaty 2 Territory, a few hours’ drive north of Winnipeg, where she lives. Like many Indigenous people, she hadn’t been raised with tradition, a result of colonialism. Her grandmother had attended a federal day school as a child, where she was taught that her culture was shameful. Paquette thought the questions insensitive. More than that, they were weird. “Dressing in traditional regalia is not a tool to get a job,” she tweeted at CIBC. The bank defended itself, tweeting back that the questions had been designed by an organization called Our Children’s Medicine, “in consultation with Indigenous community leaders and Elders.”

According to their website, Our Children’s Medicine are “Canada’s leading experts at Indigenizing employment processes, sourcing, hiring, onboarding and retaining AMAZING Indigenous talent.” They have a digital platform for Indigenous job seekers, featuring postings like the one Paquette encountered, and offer corporate trainings on topics such as “Indigenizing The Interview Process.” Their past and present clients include CIBC, BMO, Scotiabank, KPMG, and Deloitte. The organization, a registered charity since 2019, employs some Indigenous staff and is governed in part by a Toronto-based investment firm called Birch Hill Equity Partners Management. Our Children’s Medicine was founded by Josh Hellyer (the grandson of former defence minister Paul Hellyer), once a TV and film producer, a self-published author, and a mental health advocate. Hellyer is not Indigenous, but his Instagram bio reads “Indigenous ally.”

By partnering with Our Children’s Medicine, CIBC was participating in the growing national commitment to “decolonization” and “Indigenization.” The two terms are often used interchangeably, though, in short, the former refers to removing colonial influences from a system while the latter refers to incorporating Indigenous elements into a system. In practice, this has meant creating space for Indigenous people and ideas in order to correct for historical marginalization—like a human filter that sieves out harmful impurities in a range of sectors, from public institutions to private businesses. One of the most visible examples is corporate and institutional land acknowledgements—even McDonald’s does them—which recognize the dispossessed Indigenous people from that specific region. Even prisons, where the proportion of Indigenous inmates has risen by 32 percent in the past decade, have gotten on board with Indigenization: in December, without any apparent irony, the Canadian government congratulated itself on a correctional facility for Indigenous inmates constructed in the shape of a soaring eagle.

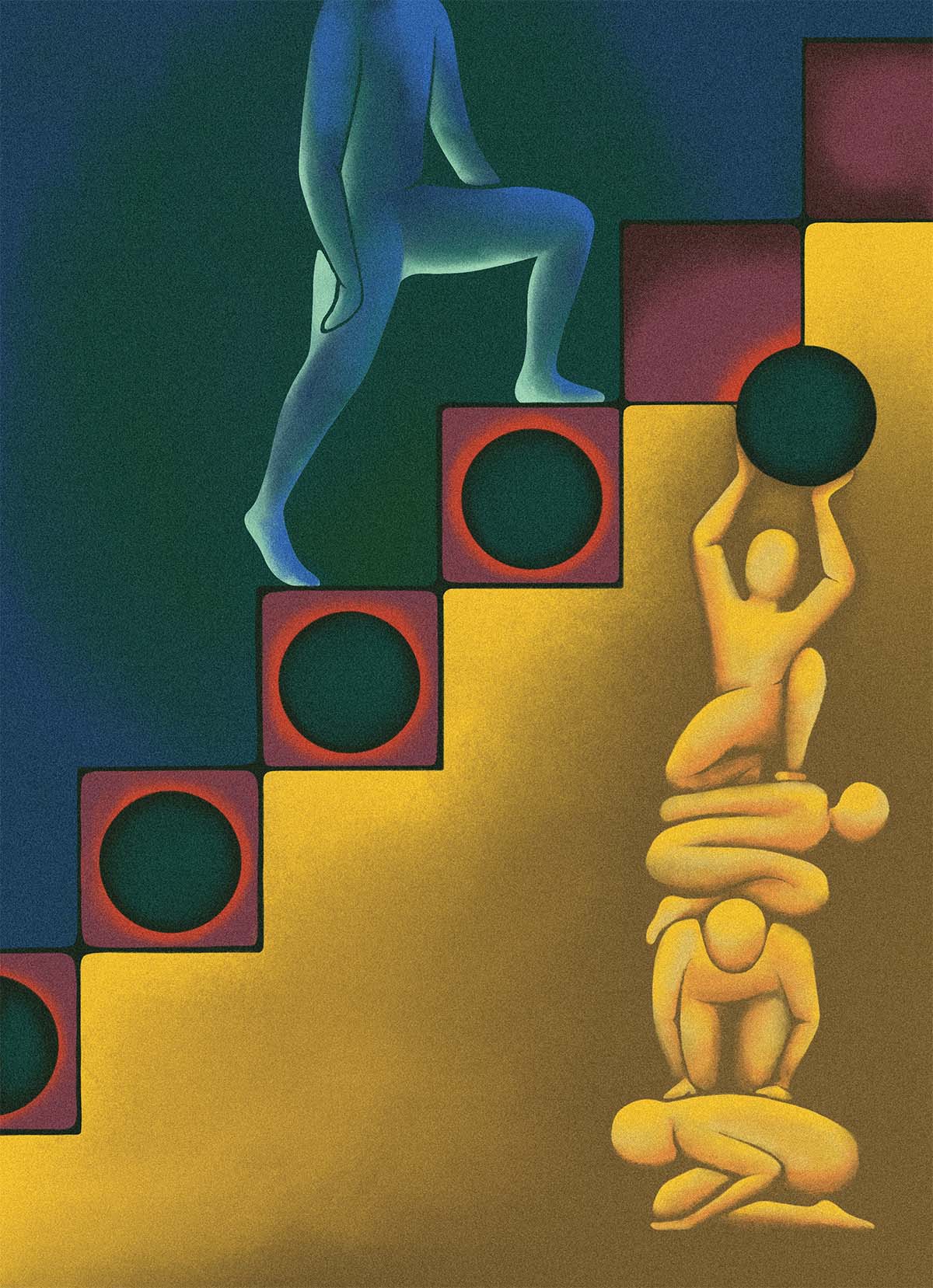

While it may seem well meaning, Indigenization has a fatal flaw: the belief that Canada can absolve itself of colonial guilt by the mere presence and participation of Indigenous people. In 2016, when Birch Hill co-founder John MacIntyre received an industry award for Our Children’s Medicine, he said, “There’s a lot of social issues that business really can’t do anything about. However, we can employ people.” It’s a perspective representative of a larger trend: companies and organizations implementing visible gestures toward inclusivity—like special questions or positions for Indigenous job seekers—with no real evidence that they are addressing the fundamental inequalities that have led to the underrepresentation of Indigenous people in the first place. Conspicuous corporate Indigenization has been a funding and marketing bonanza for employers, many of whom have tasked their hires with additional responsibilities that are unspoken and unpaid: to advise the institution on Indigenous issues, to educate their colleagues about Indigenous culture, and to serve as public examples of their employer’s politics. The result of this widespread effort to rebrand corporate self-interest as progressive benevolence has been yet another failure for Indigenous people.

In December 2015, soon after becoming prime minister, Justin Trudeau made a bold commitment for “a renewed, nation-to-nation relationship with First Nations peoples,” while standing before the annual meeting of the Assembly of First Nations in Gatineau, Quebec. The First Nations leaders in attendance cheered and clapped. “I know that renewing our relationship is an ambitious goal,” Trudeau continued. “But I know that it is one we can and will achieve, if we work together.”

In June of that year, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission had issued its executive summary on the intergenerational impacts of residential schools, informed by more than 6,500 witnesses and eight years of work. The report came with ninety-four calls to action “to redress the legacy of residential schools and advance the process of Canadian reconciliation” across a variety of sectors, including health care, media, and policing. Call to Action 92 is directed squarely at “the corporate sector in Canada” and demands “equitable access to jobs, training, and education opportunities in the corporate sector” for Indigenous people. If the TRC’s calls to action provided Canada with a road map for reconciliation, Call to Action 92 appeared as a path for organizations and institutions to transform their hiring, operational, and governance structures.

Our Children’s Medicine describes its mission as a direct response to Call to Action 92—declaring on its website that, to match the proportion of Indigenous people in population, “we believe that every major company in Canada should have at least 5% of their employees identify as First Nations, Metis or Inuit.” In addition to using their online job board, companies can pay to participate in “Indigenous Virtual Career Fairs” with “pre-screened Indigenous job seekers” to seemingly expedite the process of achieving diversity in their staff. In short, the corporate sector has promised to transform itself simply by increasing the representation of Indigenous people.

These efforts largely fail, however, because they relegate Indigenous people to the margins, leaving the employer’s core culture and values intact. Organizations become eager to hire Indigenous people, to invite them to join advisory boards or panels, or to ask them to give territorial welcomes or land acknowledgements—in effect creating visible roles with negligible power. (Many of the jobs posted through Our Children’s Medicine are for entry-level roles.) Even achieving the low bar of proportional diversity is challenging for the corporate sector. As of 2022, according to an advisor.ca article, CIBC had only 3 percent Indigenous representation among its staff and only 1 percent at the senior level; that’s still more than twice as many Indigenous staff as compared to any other major bank in Canada.

Our Children’s Medicine has defended its approach. In response to Paquette’s concerns, the organization told the CBC that the interview questions had been developed with “Indigenous Elders, Knowledge Keepers and other members of the community.” It did not specify names, but its YouTube channel features videos with Ernest Matton, also known as Little Brown Bear, a prominent public figure who, as a Métis Elder, worked with many Ontario charities and health care organizations. A 2022 CBC investigation, sparked by questions from Anishinaabe educator Deanne Hupfield, revealed his membership files with the Métis Nation of Ontario were incomplete. In the wake of the accusations, Matton retired suddenly from his role at Toronto’s Michael Garron Hospital.

The bizarre chain of events illustrates how Indigenization is seen as a service that can be subcontracted out with minimal oversight or attention. The resulting efforts are tokenizing, clumsy, and shallow. (Our Children’s Medicine also uses the name Kiinago Biinoogi Muskiiki, which the organization says is its “traditional spirit name,” but an Anishnaabemowin language instructor and Indigenous studies professor at Georgian College translated the name as the quite different “All Children Are Medicine.”) In some cases, these misguided efforts actively harm those they aim to help. The “Aboriginal Healing Program” space at Michael Garron Hospital, led by Matton before his hasty exit, has since been suspended entirely while the hospital embarked on “restorative action.” CIBC’s response on social media to Paquette demonstrates that companies are reluctant to actually take responsibility for their own efforts, instead using Indigenous partners—or partners that sound Indigenous—to deflect criticism.

Meanwhile, Indigenous people seem to be hitting a wall with institutions and companies that have failed to live up to ambitious promises of Indigenization. In November 2022, Kanyen’keháka artist Greg A. Hill was fired from his role as the senior curator of Indigenous art at the National Gallery of Canada. On Instagram, Hill wrote that he had been dismissed for disagreeing with “the colonial and anti-Indigenous” practices in the museum’s Department of Indigenous Ways and Decolonization. Last November, Anishinaabe artist Wanda Nanibush left her role as the inaugural curator of Indigenous art at the Art Gallery of Ontario following a complaint from the Israel Museum and Arts, Canada, to Stephan Jost, the gallery’s director and CEO, regarding Nanibush’s support on social media for Palestinian liberation and her criticism of Israel’s siege on Gaza. (The posts have since been deleted.) Indigenous people are often desirable institutional assets precisely because of their outspoken public and political positions; by hiring them, the institution can suggest that it is adopting their values too, or at least indicating its support. But once hired, Indigenous people are expected—like all other employees—to assimilate into the institution’s values instead, their individuality neutralized by a vast and self-serving bureaucracy.

Nanibush’s abrupt departure prompted artist Aylan Couchie to organize an open letter, signed by more than 120 Indigenous artists and scholars, declaring that “Canada’s public art institutions have reversed course on their much lauded, highly publicized and commodified commitments towards decolonization and Indigenization.” Another open letter from the Indigenous Curatorial Collective has called on the AGO to release Nanibush from any legal agreements preventing her from speaking about the departure, writing, “The silencing of her person, the erasure of her presence within your institution, has broken any illusion of relationship upon which allyship with Indigenous communities must be built.” A week after Nanibush’s departure, Jost wrote, “I hear you. I am taking this seriously and I know there will need to be a rebuilding of trust,” adding that the museum was “taking the time to deeply review and reflect on our commitments to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report.” Less than two months later, Inuk Scottish curator Taqralik Partridge resigned from the gallery. The exodus of high-profile Indigenous leaders is from many sectors: last December, all twelve members of CN Rail’s Indigenous Advisory Council resigned, in a letter that called on the company to “move beyond performative gestures, and commit itself to transformative change led by Indigenous leadership across all lines of business.”

Since the TRC released its report, Canadians and their institutions have frequently invoked their efforts to “listen and learn” from Indigenous people. It could be seen as a well-intentioned phrase but is one that is used to justify a posture of perpetual passivity and that excuses any missteps as part of a self-improvement journey that never seems to end.

To understand these failures, it’s illuminating to reflect on the mainstreaming of the term “Indigenous.” The term permeated public consciousness following Trudeau’s election, through a concerted effort by the Liberal government to rebrand Canada’s relationship with First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples. The goal was to signal the arrival of a new, hopeful era and replace the dominant terminology of “Aboriginal”—which included dissolving the federal department Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada to create Crown–Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada and Indigenous Services Canada, as well as changing National Aboriginal Day to National Indigenous Peoples Day. Public policy scholar Mathieu Landriault, who charted the vernacular shift, found that between October 2012 and October 2013, “Aboriginal” was used in newspapers nearly four times as frequently as “Indigenous”; five years later, Indigenous was the dominant term, appearing more than 4.5 times as often.

As Otipemisiwak/Métis scholar Jennifer Adese writes in her 2022 book Aboriginal™: The Cultural and Economic Politics of Recognition, “indigenous” had historically been used as an ecological term to describe plants and animals, while “aboriginal” was more commonly used for people; however, she writes, “indigenous” means “not just of a place but inseparable from it”—reflecting the way that Indigenous people are inextricably linked with their homelands. Adese charts the decline of “Aboriginal” and the rise of “Indigenous” as linguistic signposts for distinct political shifts; one can also use them to chart the growing profitability of Indigenous identities. Between 2006 and 2011, she notes, the value of the “Aboriginal cultural tourism industry” grew from $20 million to $42 million; in 2017, the Indigenous tourism sector generated nearly $3.8 billion in revenues.

As “Aboriginal” fell out of favour with Indigenous people, particularly those who saw the term as a label that had been imposed on them, Adese writes, the federal government was able to leverage the rebranding to suggest meaningful transformation and collaboration without actually changing anything else.

Nearly a decade after Trudeau’s address to the Assembly of First Nations, only thirteen of the TRC calls to action have been completed, according to the latest annual report published by the Indigenous-led Yellowhead Institute. (At this pace, the authors noted, it will take until 2081 to implement all ninety-four.) This inaction is unfolding against a national landscape of clashes between Indigenous rights and sovereignty and economic development—including the 2020 arrests of Wet’suwet’en land defenders and Tyendinaga Mohawk protesters who had blockaded rail lines in protest of the Coastal GasLink pipeline through unceded lands in northern British Columbia, as well as dozens of other battles across the country, from Tsleil-Waututh Nation in coastal BC to the Treaty 9 First Nations in Northern Ontario and Mi’kmaw homelands in Nova Scotia.

Amid these extensive violations of treaties and Indigenous rights, it’s become clear that the transformation demanded by the TRC has been usurped by generic, symbolic expressions of solidarity that treat hundreds of nations and peoples across the country as a monolith. In effect, individuals are interchangeable, and professional roles and opportunities designated for Indigenous people are rarely specific in their intent. There have been exceptions: in 2017, Vancouver International Airport signed a thirty-year agreement with the Musqueam Indian Band, which includes revenue sharing, employment, and educational opportunities and protections for environmental and archeological resources. Though Musqueam councillors recall that the airport agreed to discussions only after the nation threatened legal action, it has nonetheless led to a unique and meaningful contract. And last year, the University of Waterloo announced it would give free tuition to members of the nations whose traditional territory the university is on, a move followed by the University of Toronto.

For the most part, however, beyond ubiquitous land acknowledgements that aim for specificity, most organizations, universities, and companies remain focused on Indigenous people in a general sense. Though it seems obvious to say that an Inuk from the North, a First Nations person living on reserve, and an urban Métis person may have vastly different life experiences and cultural backgrounds, these unique perspectives are treated as equal and interchangeable by employers and institutions looking to bolster their diversity.

Flattening the members of hundreds of distinct Indigenous nations into one blurry pan-Indigenous category has led to inevitable and predictable blunders. In 2019, Pride Toronto apologized for displaying a land acknowledgement that did not name any specific Indigenous nations but invited attendees to “build a relationship with Mother Earth”; after being lampooned on social media, the festival organizers pinned the bizarre wording choice on an unspecified Indigenous person. The approach has also led to predictable and widespread fraud: experts estimate tens of thousands of people have claimed Indigenous identity based on extremely distant or specious ancestry in order to access jobs, training, funding, and other opportunities meant for Indigenous people. That fraudulent claims are often dismantled by real members of specific communities reflects the relationality of Indigenous nations; Indigenous people tend to know the people in their own communities. But in non-Indigenous spaces, there’s no expectation of familiarity or kinship; one’s Indigeneity is meant to function in isolation, in service of an organization’s noble aims.

When Inuk writer Ossie Michelin was hired as an editor at the venerated, now-defunct publication Canadian Art in 2020, he found himself “in a position that many Indigenous People working in arts institutions occupy on occasion: in a role that was created to attract Indigenous employees, but not necessarily keep them, ” he wrote in an essay for Maisonneuve. Michelin noted that hiring Indigenous employees allows organizations to apply for grants and funding to offset salaries while using those same employees as evidence of their progressive politics to extract various values from their labour.

Many Indigenous people will recognize the dynamic that Michelin is referring to. As employees, they are often performing three simultaneous roles: the one they were hired to do, plus as an on-demand educational resource for non-Indigenous employees, and also as a public attestation of their employer’s inclusivity. It’s what is known as the “cultural load.”

Haida curator Lucy Bell, after leaving her role as the first ever head of the Indigenous Collections and Repatriation Department at Victoria’s Royal BC Museum in 2020, expressed frustration with this expectation when she told APTN, “Decolonizing museums should not be left to the handful of Indigenous people that work in museums. It’s like it’s piled on: do my job and then decolonize the museum as well.”

It is something that Ian Mosby, an associate professor at Toronto Metropolitan University and co-author of the annual progress reports by Yellowhead Institute, has found frustrating. “Meanwhile, the experience of Indigenous people in those fields is extremely negative,” he says. “What is actually changing? You have a land acknowledgement, but you have no Indigenous staff, or you can’t retain them? What does that mean about your organization?”

The churn rate of Indigenous employees is a problem with multiple origins. Many Indigenous faculty have resigned out of frustration with the impossible expectations of their roles. “The university has, as an institutional priority, Indigenization. And that’s a good thing,” Allison Muri, University of Saskatchewan faculty association chief negotiator, told the CBC in 2020 after nearly a dozen Indigenous faculty resigned from the university in the space of a few years. “But the problem is, sometimes there’s a profound disconnect between the goals and actions.” Many of the departing faculty members said they had experienced racism, as did Angelique EagleWoman, who was appointed the first ever Indigenous dean of a Canadian law school when she joined Lakehead University in 2016, before resigning less than two years later. In an interview with the Toronto Star, EagleWoman said, “Systemic racism doesn’t magically disappear by bringing in the Indigenous person, even in a leadership position.”

Adese, in Aboriginal™, argues that Canada’s “only apparent solution for the poverty it has engineered is to try to force Indigenous peoples to embrace neoliberalism and neoliberalism’s goal of economic growth.” To create equality among Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians, in this paradigm, posits that bringing Indigenous people into existing corporate institutional structures will benefit both groups, a win-win strategy for reconciliation.

“What tends to happen is that reconciliation becomes exploitation,” says the Yellowhead Institute report’s co-author Eva Jewell, “where Indigenous peoples are expected to either fix the institutions they’re working in, or orient themselves to the powers that be and reconcile with the Canadian state. So we’re asked to fit into the box of the institution, and then once we’re included, the institution [feels it has become] diverse and equal.”

What began with optimism and enthusiasm has curdled into a series of failed efforts and half measures—demonstrating not only the growing chasm between words and actions but also the profound disillusionment among Indigenous people who have lent their efforts to the project of transformation, which is always somewhere just beyond the horizon, on the other side of a vast sea of superficial gestures and positive intentions.

Paquette, now twenty-three, found a new job shortly after her experience with CIBC; nobody ever reached out to her directly about her concerns over the application process. Job postings for CIBC are still active on the Our Children’s Medicine hiring platform, with a defensive caveat about the origins of the assessment questions. The regalia question has been removed, but the one about traditions remains.

As Indigenous people have grown indignant rather than placated by tokenizing efforts, enthusiasm for Indigenization within the public and private sectors has diminished and been replaced by a growing sense of fatigue and resentment. Just days after Nanibush’s departure from the AGO, artist Luis Jacob noted on Instagram that a gallery wall that once bore text about nation-to-nation relationships and the historical exclusion of Indigenous people from arts institutions had been erased. At the National Gallery of Canada, Jean-François Bélisle, who was appointed director and CEO in July 2023, the year after Hill was fired, offered an ambivalent view of decolonization in an interview last November, saying, “A gallery is a gallery. It comes from a colonial past. We’re not going to change that.” It’s not a unique sentiment.

“I think a lot of settlers and settler institutions wanted pats on the back for what they’ve already done,” says Mosby. “And when they didn’t receive them, they started to get embittered.” But what they’ve done, he says, is not enough—and not what was explicitly articulated in the TRC. “It’s quite clear from our report that in every sector, these real structural changes aren’t being made. All the sort of symbolic changes, the changes in language—those are the easy ones to make.”

It’s true that individual Indigenous people have benefited from inclusion efforts, attaining meaningful jobs and educational experiences that members of previous generations were actively excluded from. Many have used those experiences to serve their nations and communities, in addition to generating value for their employers. But these advances are conditional, and so are the freedom and opportunity that accompany them. An institution can remove an Indigenous employee who is too outspoken or politically active and replace them with a new one in order to maintain what often feels most important: internal diversity targets.

The most significant Indigenous victories have been achieved not through co-operation, as Trudeau dreamed in 2015, but by taking the government to court—a strategy that underscores how many unpaid debts have yet to be settled. Just last year, there were two multi-billion-dollar compensation settlements awarded to First Nations—$10 billion to twenty-one First Nations for the breaching of the Robinson Huron Treaty by Canada and Ontario, and $23 billion, the largest settlement in Canadian history, to Indigenous families and children affected by the child welfare system. While settlements seem like progress, they are also proof of failures: the financial toll of the government’s historical preference for offering symbolic gestures in lieu of fulfilling legal obligations. And as the country continues to prioritize token participation over meaningful consent and true equality, the liabilities will no doubt continue to grow.

Call to Action 92 specifies not only access to jobs, training, and education. It also includes “meaningful consultation, building respectful relationships, and obtaining the free, prior, and informed consent of Indigenous peoples before proceeding with economic development projects.” While CIBC, Scotiabank, and BMO have all partnered with Our Children’s Medicine to Indigenize, all three banks are also funding pipeline projects through First Nations territories that are proceeding despite strong opposition. In 2023, the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion was re-routed through a culturally significant sacred site of the Secwépemc Nation, despite the nation’s objections, and will terminate in the unceded waters of the Tsleil-Waututh Nation, which has been fighting the pipeline for years. While it’s not clear how much CIBC has spent on consultation services with Our Children’s Medicine—which earned $165,000 in 2022 for its services—it’s almost certainly much less money than the bank has loaned to the Trans Mountain Expansion project, which has received more than $18 billion in loans from private banks.

Companies and organizations can do more than simply “employ people”—than simply choosing a path of minimal resistance that turns Indigenous people into tools of corporate success rather than obstacles. A focus on inclusion has allowed companies and organizations to redirect attention away from all the other ways they might respond to Call to Action 92, ones premised on meaningful consent and recognition—ones that, for example, might require a national bank to stop funding unsanctioned development projects through Indigenous land.

Last November, CIBC received the inaugural Indigenous Reconciliation award from the federal government’s labour program for their “outstanding commitment” to reconciling with Indigenous people, including their engagement and outreach efforts. In a statement, a CIBC spokesperson reiterated their heartfelt intentions, adding, “While we have much to be proud of, there is still more we can and will do.” With financial support from CIBC, the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion is expected to be operating at full capacity by the end of 2024.