Vin Scully, who died on Aug. 2, 2022, is widely viewed as the greatest baseball announcer of all time. But for an earlier generation, his mentor, Red Barber, held that distinction.

In our recent biography “Red Barber: The Life and Legacy of a Broadcasting Legend,” we uncovered moving private letters and public references documenting the rich personal bonds between these two great voices of the game.

In 1939, Barber brought daily radio broadcasts of Dodgers baseball to Brooklyn’s fans for the first time. By the time Scully arrived in 1950, Barber – known as “the Old Redhead” – was the toast of Flatbush.

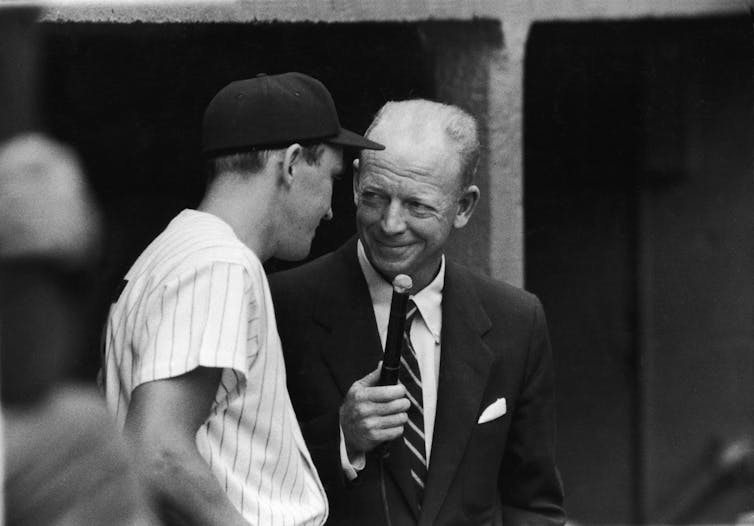

For a combined century – 33 years for Barber and 67 for Scully – the two blessed baseball fans with some of the sharpest word pictures ever painted of the grand old game. Together in the Brooklyn booth for four crucial years, from 1950 to 1953, they forged a relationship that proved to be both demanding and gratifying.

The chance of a lifetime

After Scully graduated with a degree in English from Fordham University in 1949, he papered East Coast radio stations with applications. He eventually scored an interview with CBS Radio, where Barber was director of sports. Barber came away impressed, but there were no openings at the time.

Barber later phoned Vin Scully when, at the last minute, he needed a reporter to cover a college football contest at Fenway Park in Boston for CBS College Football Roundup. Scully’s mother answered the phone and took the message for Vin that “Red Skelton” wanted to talk to him about a job – confusing Barber with the popular entertainer.

Fortunately, Scully figured out who was calling. He hustled to the park, only to learn there was no room for him in the press box. With only a light topcoat to defend himself against the cruel New England elements, he had to call the entire game from the roof, braving the winds on a chilly fall day with only a 60-watt light bulb to warm his hands. Barber, initially unaware of Scully’s plight, later wrote that when he learned his announcer had called the game from the roof, he was impressed by the young broadcaster’s stamina and even more impressed that Scully had never complained about the brutal conditions.

When Ernie Harwell, who would become the legendary voice of the Detroit Tigers, left the Brooklyn Dodgers’ broadcast booth for the New York Giants, Red Barber needed to find a replacement. He decided to go with the young broadcaster who had so impressed him – later describing Scully as “a pretty appealing young green pea … a boy who had something on the ball.”

So Vin Scully, just 22 years old, was given the chance of a lifetime, to broadcast the games of the Brooklyn Dodgers, the National League’s most successful team.

But this golden opportunity was challenging in ways Scully did not foresee.

Barber takes Scully under his wing

Red Barber, who early in life planned to be a college professor, was a tough grader. He demanded a lot of himself, and he held those who worked with him to just as high a standard.

When Vin first entered the Dodgers broadcast booth, Barber told the young man that his job was to do whatever Red and his colleague Connie Desmond didn’t want to do. He also made it clear that any Scully errors would be corrected on air for all to hear. When Barber saw Scully drinking a beer with his pregame sandwich – a common practice at the time – he told Vin he never wanted to see him do it again.

Barber was no teetotaler – far from it; leisure hours drinks were something he treasured. But he believed a broadcaster should never have a drink, even a beer, on the job. Barber reasoned if Scully made an error, something inevitable for a broadcaster ad-libbing for hours at a time, anyone who saw him sipping the press room brew would conclude that alcohol had clouded his performance.

One of Red’s broadcasting mantras was pregame preparation. So before one game, when Scully told his mentor that a Dodgers’ regular would be out of the lineup, Barber demanded to know why. Scully told him he had no idea. To Barber, that was unacceptable.

Scully quickly realized that he needed to know the “whys”; he had to get to the stadium early and spend time talking with managers and players, absorbing compelling facts and stories to keep listeners engaged during slow stretches of each contest.

The delicate bonds that develop between any mentor and mentee, though often fruitful, almost always involve some degree of resentment and frustration, likely because each member of the pair has so much vested in winning the respect and affection of the other. Some of Barber’s barbs must have stung. But throughout his career Scully always credited Red for instilling in him the discipline and values of a professional baseball announcer. He claimed that the greatest virtue of Red as a mentor “was the fact that he cared. I wasn’t just another kid in the booth, just another announcer. … He made sure that my work habits were good, and he rode me if I drifted away from his ideal of the right way to work.”

Scully in the spotlight

In 1953, Barber left the Brooklyn booth after a dispute over his pay.

Ahead of that season’s World Series between the Dodgers and the New York Yankees, the Series’ sponsor, Gillette, offered Barber only $200 per game, take it or leave it. Barber left it, and when he did not get the support he wanted from Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley, he decided to sit out the Series and sign with the Yankees for the following season.

Gillette then turned to Scully, asking him if he’d announce the Series. Scully called Red seeking his permission. Barber was genuinely moved by Scully’s request, given that his permission clearly was not needed.

All of a sudden, Scully, at the age of 25, was thrust onto the national stage. He remains the youngest person to ever call a World Series. Two years later, he announced the Brooklyn Dodgers’ only World Series win, and in 1958 he moved with the club to Los Angeles, where he would call games for the next 59 seasons.

Barber and Scully maintained an affectionate dialogue for the remainder of Red’s life.

When Barber and Mel Allen were honored by the National Baseball Hall of Fame as the first recipients of the Ford C. Frick Award, presented yearly to a broadcaster for “major contributions to baseball,” Scully wrote his old teacher, “I know as well as anyone alive what a true artist you were behind the mike. There is a great deal of you in anything I do well in play-by-play, and it will live in me as long as I am working.”

When Barber died in 1992, Scully penned a tribute in Reader’s Digest, calling him “radio’s first poet … and the most honorable man I ever met.”

At Barber’s funeral, Scully told a reporter that he was preparing to announce the fourth game of the World Series when he first learned of Red’s death. After absorbing the sad news, he began hearing his old mentor chiding him: “Now don’t you talk about me during the game. These people aren’t tuning in to hear about me. Talk about the game.”

This article has been updated to correct the year Scully graduated from Fordham.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.