In his forthcoming book, “Tactical Inclusion: Difference and Vulnerability in U.S. Military Advertising,” Jeremiah Favara, a communication scholar at Gonzaga University, examines military recruitment ads published in three commercial magazines between 1973 – when the federal government ended the military draft – and 2016. The three magazines are Sports Illustrated, Ebony and Cosmopolitan. In the following Q&A, Favara explains the rationale behind his book and discusses some of its key findings.

Why did you decide to look at these ads?

I chose to look at these three magazines because they allowed me to explore ads designed to reach different groups, namely white men, Black people and women.

Scholars have argued that content in Sports Illustrated – known for its racy swimsuit editions – has long been designed to appeal to straight white men. My own research for the book and other scholarship has found that straight white men have consistently been portrayed in recruiting ads as ideal service members.

Ad agencies J. Walter Thompson and Bates Worldwide developed recruiting plans that singled out Sports Illustrated as one of the most effective publications for reaching a high concentration of potential recruits because of the magazine’s popularity with male readers.

Advertisers contracted by the military viewed Ebony as crucial for reaching Black recruits. That’s largely because Ebony sought to balance content focusing on Black middle-class life with content covering the fight for racial inequality in American society.

Recruiting plans for the Marine Corps and the Navy all sought to place ads in Ebony, especially as part of efforts to recruit more Black officers.

Since the 1960s, Cosmopolitan has played a key role for advertisers in reaching self-sufficient working women as a consumer market. The desired reader of Cosmo – young, straight white women seeking independence – was also an ideal target of military advertisers, particularly in the 1970s and early 1980s.

Following President Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980, the military sought to decrease the numbers of military women – an effort now known as the “womanpause” – and recruiting ads published in Cosmo tapered off.

How were the ads in each magazine distinct?

In the course of looking at more than 1,500 ads published in the three magazines between 1973 and 2016, I discovered interesting distinctions. Some themes – how much money you could make in the military, the educational benefits you could access, the sense of purpose the military could provide – were similar across the different magazines. But what was really distinct was how different ads portrayed different people as service members.

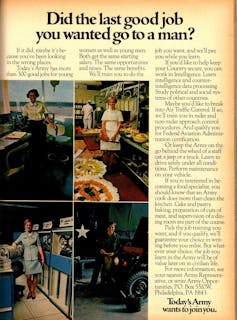

For instance, in the 1970s, the Army and Army Reserve placed ads in Cosmo that depicted the military as a way for young women – mostly young white women – to find careers and gain financial independence. The ads used headlines like “Did the last good job you wanted go to a man?” and “The best man doesn’t always get the job.” Text detailed the equal treatment – the same salaries, educational opportunities and chances for promotion – that military women would find in the military. The idea was to portray the Army as a unique site of opportunity for women.

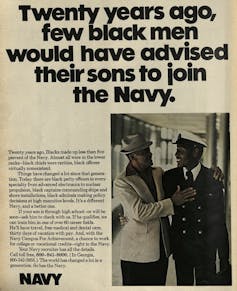

Similarly, in the 1970s, ads published in Ebony portrayed the military as a site of equal opportunity for Black men. A series of Navy ads talked about a “new Navy” where Black men had opportunities they wouldn’t have had 20 years prior.

In more recent decades, Ebony ads were less likely to use such explicit language of equal opportunities. Instead, they celebrated Black History Month by highlighting the accomplishments of exceptional Black service members from the past, such as the Montford Point Marines and the Tuskegee Airmen.

Were the magazine ads effective?

While there is no way to know if the magazine ads – and not TV ads or other methods of recruiting – were directly responsible for increasing enlistments, my research for the book found that the publication of ads targeting Black recruits and women corresponded with high rates of enlistment from those groups.

Between 1973 and 2016, the percentage of military women increased sevenfold, from 2.2% in 1973 to 15.57% in 2016. In the same time frame, Black recruits were consistently overrepresented in the military compared with their share in the civilian population. For example, in 1980, 1990 and 2000, between 19% and 22% of new enlistees were Black compared with roughly 12% to 14% of the civilian population.

To me these demographic changes show how, as recruiting ads were being designed to reach women and Black recruits, the military itself was becoming more diverse.

I am interested in exploring how ads created a certain vision of the military as what I call a tactically inclusive institution. By that I mean an institution that has been selectively inclusive of different groups but ultimately exploits the vulnerabilities of potential recruits and perpetuates state violence.

What does it mean to be ‘vulnerable’ to military ads?

The term is not one that I or other scholars initially decided to use to describe what the military does. It comes from J. Walter Thompson, an advertising agency that has been creating Marine Corps ads since 1946. In a 1973 proposal for an integrated research program for the armed forces, housed in the J. Walter Thompson Co. archives, one of the first stated objectives was to identify “vulnerable target groups.”

The agency considered those vulnerable to military recruiting as people already inclined to join the military and those who might have reservations but were seen as persuadable. Ad agencies and the military used the term “propensity” to describe these two groups. Propensity refers to the likelihood that individuals will serve in the military, regardless of whether or not they really want to join the military.

Drawing on an array of different scholars, such as Jasbir K. Puar, Grace Kyungwon Hong, Roderick A. Ferguson and Dean Spade, I think of vulnerability as being at the center of military recruiting. One is deemed vulnerable to military service because of a lack of opportunities, resources, support or cultural capital that the military can promise.

Is your book pro-military, anti-military or neutral?

The book argues that military inclusion is a form of power that furthers state violence. I am interested in studying military inclusion and recruitment advertising in order to challenge and resist the violence of the military. However, there were moments that made me think of military inclusion in a more complicated way. During an event at the Auburn Avenue Research Library in Atlanta, Georgia, I heard a panel of Black women veterans talk about their experiences in the military. They spoke about how the military provided them with financial stability, a chance to see the world and the opportunity to buy a home.

Despite the violence of the military, it is also one of the best avenues for upward mobility for many Americans. It is this tension, between seeing military inclusion as an opportunity and as a risk and form of exploitation, that I grapple with in the book.

Jeremiah Favara does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.