The NFL draft had never seen a prospect like John Elway.

Then again, in 1983, very few people had ever seen the NFL draft.

Elway, the impeccable Stanford talent with the golden right arm and the hair to match, appeared certain to be headed to the Baltimore Colts, who had the No. 1 pick after going 0-8-1 the previous year.

Yet Elway was about to do something unprecedented, and attempt to control his own destiny.

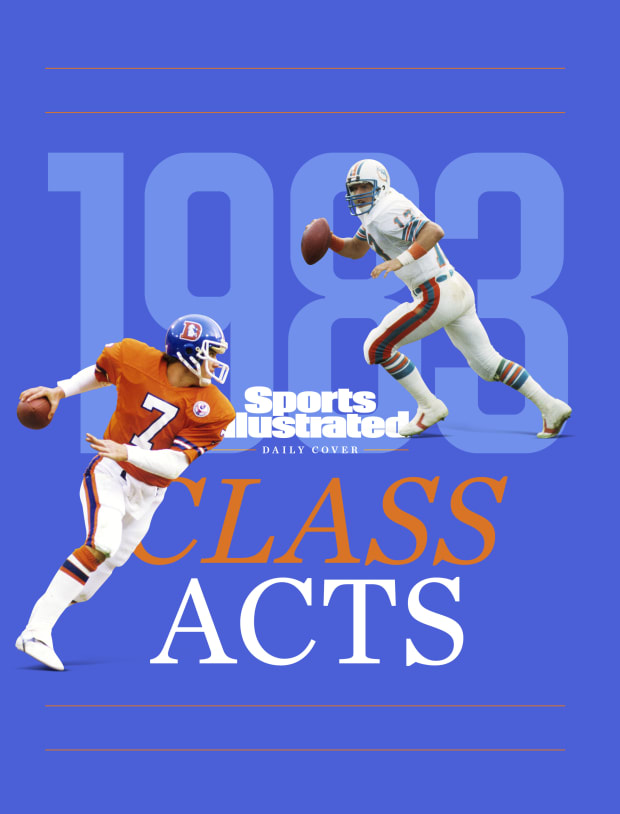

MPS/USA Today Sports (John Elway); Andy Hayt/Sports Illustrated (Dan Marino)

He made it publicly known he wouldn’t play for the Colts, wanting nothing to do with coach Frank Kush and the uncertainty of a potential franchise relocation. The decision turned the draft into a media circus. And, Elway threatened, he could always play baseball, having been a second-round draft pick of the Yankees in 1981.

With Elway’s feelings being public in the weeks before the draft, millions of football fans were fascinated by a singular question: What would the Colts do?

On Tuesday, April 26, 1983, the 48th annual NFL draft commenced.

What nobody knew was the following 24 hours—a day headlined by a record six first-round quarterbacks, including Elway, Jim Kelly and Dan Marino, who would all end up in the Pro Football Hall of Fame—would change the sport forever.

“The ’83 draft was a dramatic turning point,” says Leigh Steinberg, a headlining NFL agent since ’75. “Having quarterbacks who were considered franchise quarterbacks, leading the way to a very different NFL. Back in the ’70s, football was run on first down, run on second down and maybe you took a chance to pass on third down. All of a sudden, here comes a dramatic shift with West Coast offenses and the rest of it. … It changed the way football was played.”

The 1983 draft produced a ridiculous number of fantasy superstars

In the minutes preceding the first pick, ESPN’s fourth annual telecast consisted of speculation on potential trade partners for Baltimore. The Patriots were believed to be offering multiple first- and second-round picks. The Chargers were thought to be involved in talks while at an impasse on long-term negotiations with quarterback Dan Fouts. The Raiders were attempting to acquire the Bears’ first-round selection, giving owner Al Davis two firsts to work with.

Then, Howard Balzer of The Sporting News—working for ESPN as a live analyst alongside Sports Illustrated’s Paul Zimmerman and host George Grande—provided a final thought before the cameras cut to an interview with NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle.

“Denver might even be a late possibility as well.”

At 8 a.m. ET, Rozelle stepped to the microphone at the New York Sheridan Hotel and put the Colts on the clock. Nine seconds later, the card was turned in.

Quarterback, John Elway, Stanford.

In the hotel ballroom and around the country, people had a reaction. It’s probably the first draft pick in NFL history for which that can be said.

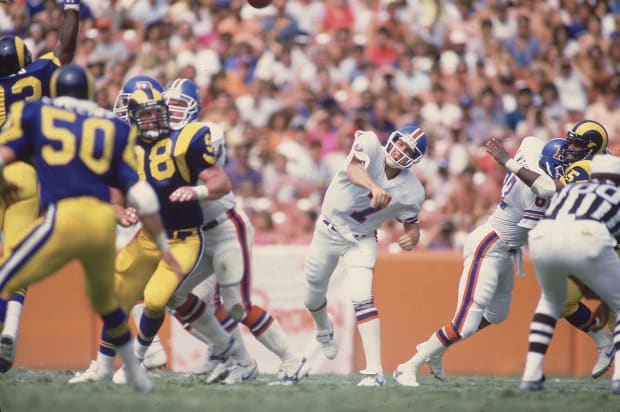

Andy Hayt/Sports Illustrated

Although Elway was off the board to Baltimore, he was now on the market. Still resolute to never play for Kush and the Colts, the real-time bidding war for the Washington State native intensified. The Raiders, then entering their second season in Los Angeles, were still working to complete a deal with Chicago, while other teams called Baltimore general manager Ernie Accorsi in hopes of finding the right price.

With potential trades swirling, the picks rolled on. Future Hall of Fame running back Eric Dickerson went second to the Rams. The Bears, who ended up keeping their choice instead of trading with the Raiders, selected offensive tackle Jimbo Covert, another man ticketed for Canton.

Yet Covert wasn’t the intriguing name from the University of Pittsburgh that day. That was Marino, a rocket-armed quarterback who muddled through a poor senior season of 17 touchdown passes against 23 interceptions, fueling rumors of drug use that have never been confirmed.

“It was the perfect example of how on draft day, with people spread across the country in their headquarters, a rumor can affect the perception of teams drafting,” Steinberg says. “If a player doesn’t go where he’s theoretically projected to go, then teams in the heat of the draft are afraid to pick the player, because there must be something other teams know that they don’t. So that was a surprise, because based on scouting and the predraft, we thought Marino might have been number two [among quarterbacks], and that didn’t happen.”

While Elway was the obvious first choice, many assumed Marino would be the next quarterback chosen among a group of potential first-rounders, including Penn State’s Todd Blackledge, Illinois’s Tony Eason, Miami’s Kelly and UC Davis’s Ken O’Brien.

Yet it was Blackledge who went No. 7 to the Chiefs. At 14, the Bills used their second first-round pick on Kelly. And Eason went to the Patriots one pick later.

Marino continued to slide, reaching his hometown Steelers, which held the 21st selection. Pittsburgh had Terry Bradshaw and believed he could play a few more seasons, yet owner Art Rooney wanted the local product. However, on draft day, Rooney stayed out of the decision-making process, allowing coach Chuck Noll and the front office to make the call.

Ultimately, the Steelers took Texas Tech defensive tackle Gabe Rivera, whom Noll believed could be a successor to Joe Greene on the defensive interior. Rivera played six games before an automobile accident rendered him paralyzed.

As for the selection, many in the building wanted Marino, including a 27-year-old defensive backs coach named Tony Dungy. Dungy, who eventually became a Hall of Fame coach, still remembers Marino’s workout for the Steelers in the predraft process.

“The wind had to be blowing 100 mph in the stadium, blowing everywhere,” Dungy says. “He came over with his two receivers, Julius Dawkins and Dwight Collins, and he’s throwing balls through this wind, putting the ball right on the money, and they’re dropping everything. I’m thinking to myself … no wonder he didn’t have a good senior year; these guys can’t catch.”

Three choices later, the Jets turned in their card. Stunningly, it was O’Brien, who went 24th to the Jets, shocking the smattering of fans in the ballroom.

Finally, Marino was taken by coach Don Shula and the Dolphins with the first round’s penultimate pick at No. 27.

“It’s really funny how Dan Marino fell, just because of certain little things people said about him and whatever,” says Phil Simms, Giants quarterback from 1979 to ’93 and current NFL on CBS analyst. “He was big, athletic, and had a really good arm. He would be the first or second pick of the draft even in today’s world as far as talent goes.”

The first round concluded with Washington selecting future Hall of Fame corner in Darrell Green, giving the draft seven such stars across its first 28 picks.

For a moment, the drama stalled; Elway was stuck, and Marino had a home.

Six days later, Elway and the Colts stole every back page in America.

Elway was traded during a meeting between Denver owner Edgar Kaiser Jr. and Colts owner Robert Irsay. The deal remains one of the most lopsided in NFL history. Baltimore received a 1984 first-round pick, backup quarterback Mark Herrmann and guard Chris Hinton, whom the Broncos took with the fourth pick the week before, while Denver received Elway.

Still, even with all the initial chaos, the 1983 draft’s legacy was only beginning.

Manny Millan/Sports Illustrated

While only Elway won a championship—he ended his career with consecutive titles in 1997 and ’98 after three lopsided Super Bowl defeats in ’86, ’87 and ’89—the quarterbacks defined an era while starting the changeover from a run-based league to the present-day, pass-happy NFL.

From 1984 to ’93, the quartet of Marino, Elway, Kelly and Eason represented the AFC in nine of 10 Super Bowls. They also totaled 18-of-34 AFC Pro Bowl quarterback spots during that span, winning MVPs in ’84 (Marino) and ’87 (Elway).

Marino’s 1984 season remains the finest in NFL history when era-adjusted. He shattered single-season passing records with 5,084 yards and 48 touchdowns, leading the Dolphins to Super Bowl XIX. When Marino retired after the ’99 season, he owned the all-time records in both of those categories, throwing for 61,361 yards and 420 touchdowns.

“Those guys became the most important guys on the team,” says Bruce Matthews, the No. 9 pick in 1983, who became a Hall of Fame offensive lineman. “It definitely transformed the league, especially the way Dan Marino did it so early, and with the impact he hit the ground running with in Miami. It was totally quarterback driven.”

In Buffalo, the Bills were initially left empty-handed. Kelly dreaded playing in cold weather after playing at the University of Miami (Florida). When the United States Football League’s Houston Gamblers offered him a deal, Kelly bolted for the new league. He stayed in Houston for three years until the USFL folded, joining the Bills in 1986.

Once he arrived, Kelly helped revive Buffalo. The Bills won four consecutive AFC titles from 1990 to ’93, only to lose each Super Bowl. Still, Buffalo is largely remembered for sustained excellence while also ushering in the K-Gun, a no-huddle offense that became a staple within many NFL offenses over the following decades.

“Looking back, [the 1983 draft] was a great influence on the NFL,” Simms says. “Having all those quarterbacks in the draft, and sparking interest for all those people who cover the draft, and the coverage you get for the NFL. John Elway was very special, Marino set the league on fire right away, that changed a lot of stuff. There’s no doubt. … It did start to change the game, where you started to see three wide receivers, [and] it affected throwing the ball down the field more.”

The 1983 draft also helped spark necessary change on other fronts.

Five years earlier, University of Washington quarterback Warren Moon declared for the draft after leading the Huskies to a Rose Bowl win over Michigan. Despite his prodigious talent, Moon wasn’t given the opportunity to pursue an NFL career as a quarterback largely because he was Black.

Moon went to the Canadian Football League and played for the Edmonton Eskimos, winning five consecutive Grey Cup titles.

In 1984, one year after the mass influx of young quarterbacks, Moon entered the NFL as a free agent. He had 12 teams bidding for his services before he settled on the Oilers, who were so desperate, they also hired former Eskimos coach Hugh Campbell to help close the deal.

“It was only one year [after the 1983 draft], and those guys were just getting their feet wet, but it was apparent that you needed a special guy at that position,” Matthews says. “There was so much excitement when Warren signed with the Oilers. We felt now we’re a viable contender because we have a franchise-quality quarterback.”

Lane Stewart/Sports Illustrated

Even before Elway’s draft drama in 1983, the league was already in disarray. The NFL had just completed the 1982 season, a nine-game sprint compacted by a 57-day players’ strike that ran from Weeks 3 to 10. As a result, the playoffs were bastardized, becoming something known as the Super Bowl tournament. Sixteen teams gained entry, eight per conference, including the sub-.500 Lions and Browns.

The season concluded with a kicker winning NFL MVP honors for the first and only time in Washington’s Mark Moseley. Washington won the Super Bowl, beating the Dolphins 27–17.

On the field, the league was having a youth crisis at quarterback. The 1982 Pro Bowlers were Dan Fouts (31), Danny White (30), Joe Theismann (33) and Ken Anderson (33). Other future Hall of Famers such as Bradshaw and Ken Stabler were aging, with Bradshaw a year from retirement and Stabler a mere two.

Only the 49ers’ Joe Montana was an established star and less than 30 years old. Yet San Francisco was coming off a dismal season in which it hoped to repeat as Super Bowl champions, going 3–6 and missing the playoffs. Montana was a star, but hardly the meganame he’d eventually become.

Still, more bad news for the establishment was arriving.

A new venture, the United States Football League, launched in March 1983. It was poaching top-tier college talent, including New Jersey Generals running back Herschel Walker, Philadelphia Stars linebacker Sam Mills and Michigan Panthers receiver Anthony Carter.

Only 13 years after the American Football League had merged with the NFL, the USFL felt a worthy competitor. It was backed by significant funding, including owners such as John Bassett and eventually, Donald Trump. The USFL also had multiple TV contracts with ABC and ESPN.

The USFL was an upstart, but its mere presence had a significant impact on the established league. NFL players benefited from its existence, including Kelly, who signed a fully guaranteed five-year deal for $3.3 million.

“When a player signed a contract prior to 1993, there was an option clause at the end of it,” Steinberg says. “The option clause only forced a team to make an offer that would be the previous offer plus 10 percent. From a leverage standpoint, negotiating then was like dignified betting. … The player was never free for a single day to do anything to negotiate with the team that drafted him. The USFL created competition and leverage for the first time since the [World Football League] and before that, the AFL. All of a sudden, players had a choice.”

Eventually, the USFL brought an antitrust lawsuit in 1986 against the NFL and won $3.76, dooming the new league. But in ’83, the threat was real.

Kirby Lee/USA TODAY Sports

While the 1983 draft changed football on the field, it had an equal impact off it.

“I’ll never forget what Pete Rozelle said after [ESPN executive] Chet Simmons approached him before the first one about televising the draft, and said, ‘Hey, we would like to televise the draft,’” Balzer says. “Rozelle said something like, ‘Why in the world would you want to do that?’”

In the 40 years since the Elway epic of 1983, the NFL turned an event Rozelle couldn’t fathom as worth being televised into the league’s second-biggest staple behind only the Super Bowl.

In 1980, ESPN televised the draft for the first time. Three years later, the intrigue surrounding the ’83 draft forced the event onto the NFL calendar, an oasis in the offseason for fans to invest.

“You could say that was when the draft on TV really came of age, just because of what a historical draft it was, because of those quarterbacks,” Balzer says. “I don’t think there’s much doubt about that.”

In 2022, the draft was simulcast on ESPN, ABC and NFL Network, averaging 10 million viewers in Thursday-night prime time for the first round. For comparison’s sake, the ’22 NBA draft averaged three million viewers, up from 2.2 million and 2.1 million the previous two years, which were impacted by COVID-19.

From 1965 to 2014, the draft was held annually in New York City, moving around to different venues within Manhattan. However, with the league turning the draft into a must-see, three-day event starting in ’10, the business side went into hyperdrive. The league began taking bids to become the host city. In recent years, the draft has been put on by Chicago, Philadelphia, Dallas, Nashville and Las Vegas.

This year, Kansas City will host the draft April 27–29 and spend nearly $3 million to prepare. The city expects to bring in at least $102 million as a result. That might be a conservative figure. According to Newsweek, Dallas made $125 million, while Nashville collected $220 million.

Come April 27, commissioner Roger Goodell will put the Panthers on the clock for the first pick in the draft.

When he does, NFL casuals and diehard fans alike will be watching. They’ll be welcomed into Kansas City’s Union Station by hosts, analysts and personalities of multiple networks.

There will be live coverage from both the draft’s site and myriad team headquarters, with war rooms having cameras in the corners to catch real-time reaction from front offices and coaching staffs. Many top players will be on hand to walk the red carpet before the draft, and then they’ll walk onto the stage for a bro hug from Goodell after they’re selected. The few who don’t attend will likely have cameras trained on them wherever they may be, with networks sure to record any meaningful reactions.

Ultimately, the 1983 draft has proven an important moment in time. And the measure of a moment is not only how long it’s remembered, but for its lasting impact.

By that standard, few American sporting events have ever meant more to their game.