Earlier this year, New York-based designer Bibhu Mohapatra styled his models in cashmere stoles for his FW’23 collection at the New York Fashion Week. Collaborating with Janavi India, Jyotika Jhalani’s luxury cashmere label, he created looks that blended stoles and shawls seamlessly with dresses, pantsuits and midi skirts. From a practical accessory to becoming a statement, the traditional Indian shawl is reinventing itself in dramatic ways.

Designers have been exploring the possibilities of the shawl, contemporising its scope and pushing it to the mainstream. New designs and techniques are being tried out and ancient weaves are being revived, all the while incorporating ethical practices to bring out standout pieces that not just serve as accessories, but also tell a story — of their place of origin, the people who make them and the heritage of the region.

Jyotika’s label is an ode to her birthplace, Kashmir. When she launched Janavi India in 1998, she wanted to showcase the essence of fine Indian pashmina while appealing to a global market. “I knew I wanted to create shawls that were Indian, yet international in look and feel,” she says.

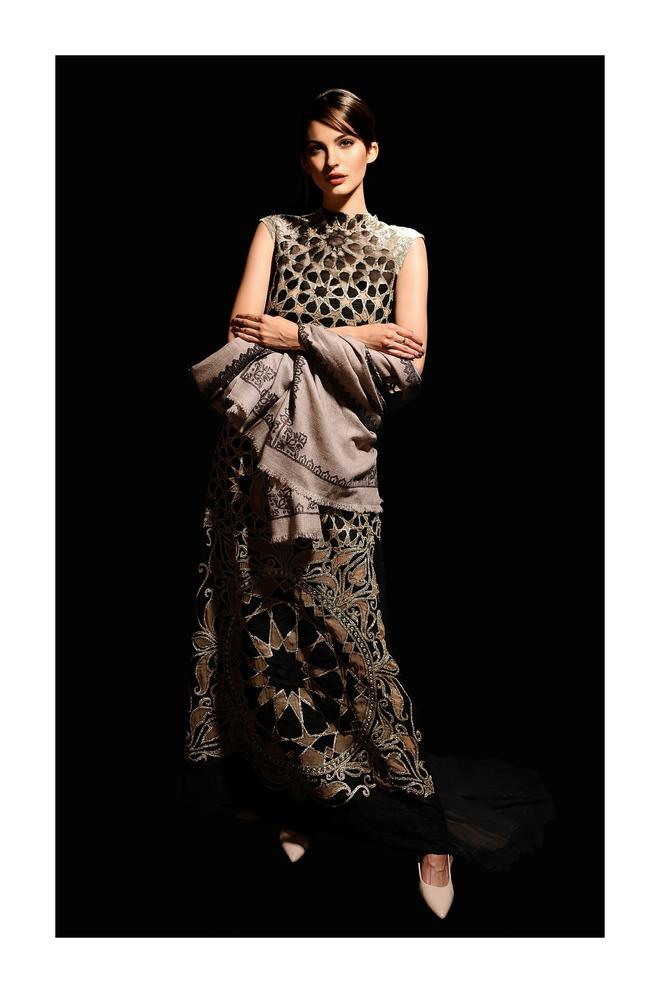

Janavi India’s design aesthetic evolved thus, using Indian-inspired embroidery and embellishments directly on fine pashmina. It experiments widely with styles — hand-painted, printed, using classic weaves and lace and embellished with crystals. “This is also why I like to call them wearable art,” Jyotika adds. She has a team of 400 artisans working at her atelier in Noida. “The shawl is so versatile. In India, every culture has one. Showcasing it in the global market, my idea was to carve a special place for the shawl — as a replacement for the trench coat and jacket. It is an easy accessory to carry and a clever one to dress up or down.” Janavi India shawls cost up to ₹1,40,000.

It has showrooms in New Delhi and is sold through international retail outlets including Bergdorf Goodman, Saks Fifth Avenue, Harvey Nichols, Liberty, Lane Crawford among others.

The Kashmiri identity is the driving force behind designer Zubair Kirmani’s label Bounipun. Zubair moved from the bustling New Delhi/NCR to his home in Srinagar four years ago, consumed by a desire to be connected to his land. “I wanted to work with artisans, I wanted to be involved in every step of the way,” he says. “A lot of pashmina products sold in market are not authentic and that brings negative impact to the trade. By working here, using local resource and talent, we want to showcase the premium pashmina from Kashmir, that is beyond the Kashmiri shawl,” Zubair adds.

His statement pieces in pashmina incorporate elements of ethnicity and folklore. Each motif is inspired by the region. For instance, his Karakul edit includes a piece that features the snow leopard, known to be found in central and north Kashmir. “With each piece, I am trying to create something that is rooted in the Kashmiri ethos, yet bears my signature,” he adds.

The slow fashion label works with local artisans. “Each shawl has about 15 steps to reach completion — from sourcing the raw material to cleaning it, spinning the yarn, weaving on traditional hand looms… it is a labour of love,” Zubair adds. “I want my clients to feel the heart and soul of the people who have worked on the piece.” The Karakul range also showcases designs inspired by khatamband, a Kashmiri woodwork characterised by geometrical patterns employed in the construction of ceilings. The range uses high quality natural pashmina which is not dyed and the colour of the shawl/stole comes from the embroidery.

“The pashmina is a complex, fascinating fabric. It reveals something new each time. We are still exploring its possibilities,” adds Zubair, who has tried wall art by repurposing pashmina shawls as wall hangings and using calligraphy on pashmina. He has clients across Europe, the Gulf countries and India. A Bounipun shawl is priced upwards of ₹35,000.

It is a similar connection to their Ladakhi roots that led Stanzin Minglak and Sonam Angmo to build their slow fashion label, Lena Ladakh Pashmina. “The history of pashmina and Ladakh are inextricably linked. Ladakh has been exporting pashmina as a raw material to be worked upon by talented Kashmiri artisans, but never benefitting from its own rich heritage. We wanted to change this and create pashmina shawls in Ladakh, with a distinctive Ladakhi identity,” says Stanzin.

What started with seven women artisans from various parts of Ladakh in 2016 has now grown to a community of 37 artisans. “Ladakhi pashmina is a very new concept in the market,” Stanzin adds. But, the label has fans around the world. “We use the traditional Ladakhi spinning method using a phang (spindle), plying and twisting on a ju-phang (twisting spindle).

The wool is sourced from the Changthangi goat, which survives under harsh weather conditions. The temperature can touch -40 degrees Celsius. The wool, from the underbelly of the goat, is not sheared and is collected when it is shed naturally in summer,” adds Stanzin. Lena produces in small batches and uses only locally-sourced natural dyes. “This results in a range of products that have a distinct Ladakhi identity and are markedly different from traditional Kashmiri pashmina,” says Stanzin.

“There is a general notion that pashmina is synonymous with the thin shawls from Kashmir. We at Lena try to educate potential customers about Ladakhi pashmina. We organise workshops, which allow participants to get a hands-on experience of spinning, weaving a crafting,” says Stanzin. “Through these workshops and story-telling that we do, we have been able to shine the spotlight on the thicker, versatile and distinct pashmina shawls of Ladakh,” says Stanzin. Lena has a store in Leh and also sells in Boston, New York and San Francisco.

Self-taught designer, and influencer Sugandha Kedia’s love for pashmina shawls was re-kindled while on her travels around the world. She learnt that pure pashmina had passionate followers and she was inspired to create her own range. Dusala was launched in 2020, designed to appeal to the younger demographic.

“Despite being exquisitely crafted, shawls were overlooked by the younger crowd. Witnessing the sheer dedication, passion, and patience that goes into crafting a single shawl, which can go anywhere between 4,000 to 17,520 hours, we took it up as a mission to bridge this generational gap,” says Sugandha.

The brand reimagines the shawl as jackets and capes. It has also collaborated with designers such as Amit Aggarwal and stylists such as Ami Patel. “We ensure that the artistry behind each shawl continues to thrive and resonate with people of all ages.”

Dusala’s range of shawls, scarves and stoles for men and women also experiments with fabric, trying out pashmina silk, and pashmina cotton, which make them suitable for a wider range of climates. Dusala’s range starts at ₹11,000 and can go up to ₹3 lakh.

In the past year, designer shawl brand Taroob has recorded 100% growth in the domestic market, says Sanchit Anand, one of the founding partners of the Amritsar-based brand. Launched in 2021, the label has held pop ups in New Delhi, Kolkata, Hyderabad, Chandigarh and Chennai and it retails through multi-designer stores in India and abroad. Interpreting the pashmina shawl in modern ways, blending art with it, the label aims to create its own range of heirloom pieces.

While it has a kalamkari print pashmina shawl, it is working on using traditional Indian art such as Warli, pichwai and Mughal Darbar on pashmina. “We are curating a collection inspired by Indian art,” says Sanchit. “The shawl is no longer just a winter accessory, people are increasingly using them even in office spaces, for a semi-formal look.” The range, which falls into the mid-luxury segment has products that start at ₹1,400 and go up to ₹25,000.

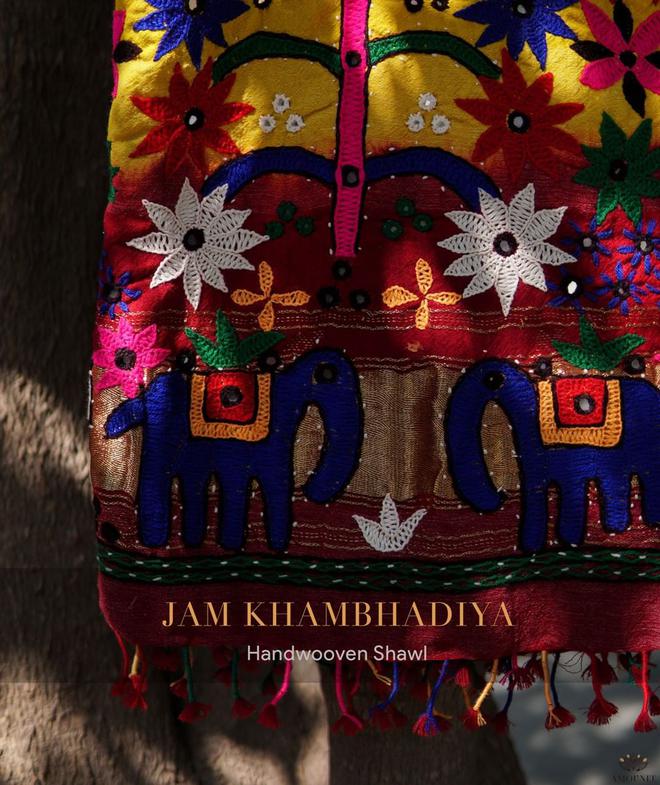

Looking beyond the lure of the pashmina, Kacchi woollen shawls are also being revived. Amounee, an Ahmedabad-based collective connects artisans to the urban buyers. It works with weaving clusters in the Jamkhambaliya region near Jamnagar in Gujarat, to bring out its Jam Khambadiya range of shawls that are in merino wool with brightly coloured traditional aari embroidery.

Megha Das, one of the directors of Amounee, who also takes care of strategy and planning, says the brand works with two families in Jamkhambaliya. “A Jam Khambaliya shawl is a work of art. One shawl can take up to 15 days to make,” adds Megha. The shawls are priced at ₹2,000 upwards.

Traditional Kachchi woollen shawls were woven by the sheep herder community (called Bharwad) for protection in winters and they were made of locally-sourced sheep wool. “This desi wool is rough. So for commercial purposes, we source wool silk and cotton from Ahmedabad and Bhujodi in Gujarat, Ludhiana in Punjab,” says Megha.

Just as much as they spell high fashion, these shawls are a nod to India’s rich textile heritage and craftsmanship. Zubair sums up, “As I run my fingers over the patterns and designs, I am filled with a sense of appreciation for the artisans who have put their heart and soul into this beautiful piece of art.”