Driven by conspiracy theories and a deep distrust of the federal government, the Oath Keepers actively recruit cops and service members who are asked to disregard official orders the group deems unconstitutional.

Members have faced a litany of alarming arrests since the group was founded in 2009.

An Oath Keeper was notably convicted in a 2010 plot to take over a Tennessee courthouse and detain officials after a grand jury refused to indict President Barack Obama for not being the legitimate U.S. president — the central claim of the debunked “birther” conspiracy theory.

Yet a top Chicago police official insisted the early years of the group were benign as she tried to explain why an officer, Phillip Singto, was allowed to remain on the force after admitting to signing up with the organization.

“He joined Oath Keepers the way it was then,” Traci Walker, deputy chief of the police department’s Bureau of Internal Affairs, said during a contentious City Council hearing this year. “It kind of morphed into something it is today.”

Walker’s public whitewashing of the Oath Keepers’ history underscores the department’s unwillingness to aggressively investigate officers linked to extremist groups.

Read the full investigation and see more documents, videos and interactive elements at graphics.suntimes.com.

The internal affairs bureau failed to investigate most officers found in a leaked membership roster, and it took five months to seek interviews with Singto and the two other cops it targeted.

As the investigation played out, a leading civil rights group sent a letter to the city’s second-ranking police official naming eight Chicago cops whose personal information was included in the leaked data.

“It is important to note that inclusion on this list means that at some point they signed up for membership,” the Anti-Defamation League wrote to then-police department First Deputy Supt. Eric Carter on Aug. 8, 2022. “The fact that a member of law enforcement joined the Oath Keepers is extremely concerning and warrants investigation.”

But the scope of the investigation wasn’t expanded, and police officials ultimately determined that joining the Oath Keepers does not constitute a rule violation.

When WBEZ and the Sun-Times raised questions about the ADL letter, a police spokesperson last week said the department was opening a new investigation into the allegations against the officers who were named in it.

Eleven cops linked to far-right groups remain on active duty in the department, including Singto and eight others who were listed on the Oath Keepers’ roster but weren’t targeted in the initial internal affairs probe.

Only Officer Robert Bakker, linked to the Proud Boys, has been disciplined. He was suspended for 120 days and didn’t face dismissal for lying to investigators, even though officials have long pledged to purge the department of officers who make false reports.

“I don’t know any other jobs really where they spend so much time defending somebody who they should normally cut,” said 40th Ward Ald. Andre Vasquez, months after having a testy exchange with Walker during the hearing. “It’s wild to me, and we all suffer for it.”

Mayor Brandon Johnson has vowed to fire cops with clear ties to extremist groups, but he has yet to take action on his campaign promise. His handpicked police superintendent, Larry Snelling, said the issue is a high priority for him.

“There’s no place on the Chicago Police Department for individuals like that,” Snelling said in an interview last week. “This is right at the top when we are talking about community trust and rebuilding the trust with the community.”

Snelling worked at the police academy with some of the officers linked to the Oath Keepers, including Singto.

Before Johnson was elected mayor, members of a new civilian oversight panel were working with police officials to broaden a policy that bars officers from joining street gangs and other criminal organizations to include hate and extremist groups.

Garien Gatewood, Johnson’s deputy mayor for community safety, said the administration is working with the department and the civilian panel to determine next steps.

“We’re gonna have to do some deep digging to root this out,” Gatewood said. “These are issues that we genuinely have to address. We have to find ways to hold folks accountable. We have to find ways to make sure people who are protecting our communities are actually invested in protecting our communities.”

Jeff Tischauser, a senior researcher with the Southern Poverty Law Center, said Johnson’s administration has a unique opportunity to work with residents to get it right.

“There’s no set standard of what to do in this situation among law enforcement organizations,” Tischauser said. “And I really feel, because this conversation is already happening in Chicago, we can be the leader at the municipality level in trying to figure it out.”

‘The police department we deserve’

The police department opened its investigation of the Oath Keepers after National Public Radio reported in November 2021 that the names of 13 active cops appeared on a leaked membership roster.

Internal affairs investigators didn’t obtain that list, which is now available online.

Instead, Singto and two other cops were targeted because they appeared to mention the Oath Keepers on the website of a firearm training firm they worked for. A link to the company’s website was included in the NPR story.

It wasn’t until five months later, in April 2022, that Sgt. John Bartuch and his team began seeking interviews with the three officers.

One of those officers, Christopher Hoffman, a former member of the police department’s notorious Special Operations Section, had already retired by that time.

Another officer, a Black cop, told investigators he never joined the Oath Keepers. His name doesn’t appear on the membership roster, and a portion of his profile on the firearm training firm’s website was apparently copied from Singto’s section by mistake.

The internal investigation of Singto was repeatedly criticized by the city’s inspector general as not being aggressive enough.

Singto told investigators he joined the Oath Keepers in 2010 or 2011 because he shared the group’s beliefs and wanted access to its website. He said he remained a member for three or four years, paying yearly dues of $13 before he “lost interest.”

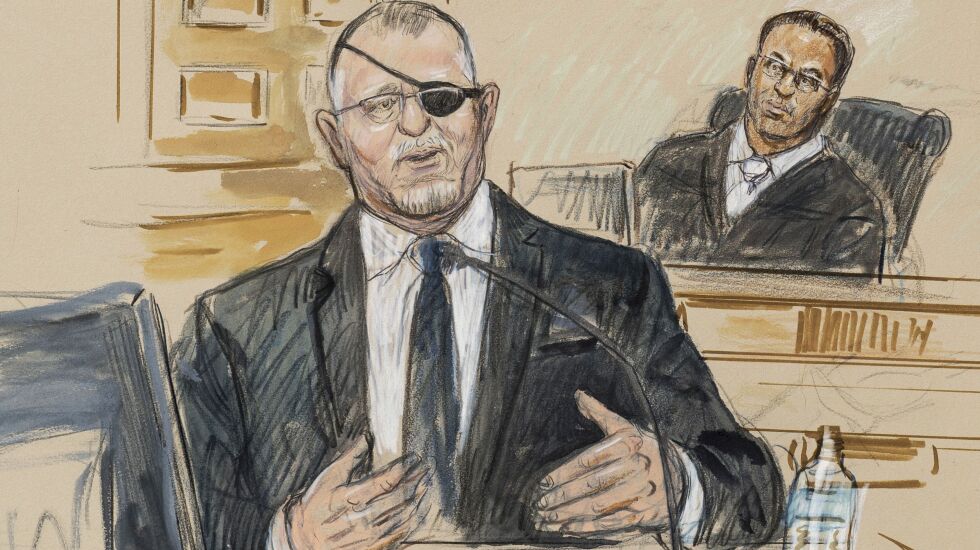

During that period, Oath Keepers founder Stewart Rhodes framed gun control as a form of “Orwellian” overreach and decried the “globalist power elites” he claimed were plotting to install a one-world government.

The Oath Keepers website was filled with revolutionary bluster and even displayed a Chicago Police Department patch when Singto was a member, according to the inspector general’s office.

Rhodes and other members engaged in an armed standoff with authorities at a Nevada ranch in 2014 — a lengthy conflict that led to federal convictions of at least two Oath Keepers.

Despite those cases and others prosecuted in federal court, a Nov. 5, 2021, memo between top officials in internal affairs singled out the Capitol riot as “the group’s only criminal activity,” citing information from FBI Special Agent James Rife.

So far, dozens of people associated with the Oath Keepers have been charged in connection with the riot. Rhodes has been sentenced to 18 years in prison on sedition charges.

Investigators never pressed Singto on his vague membership timeline, even though his profiles on LinkedIn and the training firm’s website referenced the Oath Keepers when NPR published its story. He claimed he wasn’t involved in the planning of the Capitol riot and hadn’t attended any events with the group.

In a closing report, Bartuch found that none of the allegations against the three officers were sustained. In June 2022, Inspector General Deborah Witzburg’s office asked internal affairs Chief Yolanda Talley to reopen Singto’s case to investigate further.

Among other things, the letter urged internal affairs to interview Singto again and compel him to produce any records related to his membership in the group. It also called for an analysis of whether membership violated rules that prohibit officers from bringing discredit upon the department and acting against its goals.

That September, Bartuch sent a memo to Talley stating that “no additional evidence was presented or found to seek authorization of the Superintendent to investigate these allegations any further or change the initial finding.”

Bartuch claimed he couldn’t compel Singto to hand over any documents without subpoena power.

“It was mentioned that memberships into organizations in itself is not a rule violation,” Bartuch said, referring to a conversation with the inspector general’s office and the police department’s then-General Counsel Dana O’Malley, now Snelling’s chief of staff.

The inspector general’s office shot back in a January report that a police department order requires officers to provide “all requested documents and evidence” in its control.

“It would have been plainly within BIA’s authority to compel information and documents from the accused member in furtherance of its investigation if it had determined to do so,” the report stated.

In an interview, Witzburg said the police department must take a “more aggressive” approach to investigating alleged extremists in its ranks.

“It’s the only way to foster trust in the police department, to foster legitimacy of not only the police department, but the disciplinary system specifically,” Witzburg said. “And that’s why I say we will get the police department we deserve through our handling of these cases. There is no room in the Chicago Police Department of the future for members who associate with extremist hate groups.”

‘It’s hard to imagine an issue more important’

Witzburg’s office has also pushed the department to reopen investigations of Bakker and Officer Kyle Mingari, who was photographed wearing a mask associated with the Three Percenters militia movement at a racial justice protest in Chicago in June 2020.

Bakker was suspended after a lengthy investigation into his close ties to the Proud Boys, a neo-fascist group known for engaging in political violence. Former Proud Boys Chairman Enrique Tarrio and other leaders have been convicted of seditious conspiracy in connection with the Capitol riot.

Although investigators concluded Bakker committed the fireable offenses of making “false” and “contradicting” statements, the police department signed off on a mediation agreement that suspended Bakker for 120 days.

The police department offered conflicting explanations. Supt. David Brown claimed investigators didn’t have enough evidence to prove Bakker had associated with the “Proud Boys or any other hate group.” But the head of internal affairs said the FBI didn’t list the Proud Boys as a hate group.

According to police, internal affairs is still investigating Mingari’s connection to the Three Percenters, an anti-government movement that has sprouted a network of militia groups and was linked to a plot to kidnap Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer.

Witzburg slammed all three investigations as being inadequate and “materially deficient,” but she wouldn’t say why she asked the police department to reexamine the Mingari probe, which has already been closed twice.

Witzburg said there are rules on the books that prohibit officers from joining extremist groups. And she noted that investigators have a variety of tools to enforce those rules, like reviewing body-worn camera footage and searching social media accounts.

“These are hard cases, no two ways about it,” she said. “There are First Amendment issues to contend with, there are investigative resource constraints. But it’s hard to imagine an issue more important.

“If we are serious about improving the quality of the relationship between the Chicago Police Department and the communities it serves, and if we are going to ask people to trust the police department, we must handle these cases appropriately.”

Chris Taliaferro, alderman of the 29th Ward and a former police department internal affairs investigator who presided over the City Council’s Public Safety Committee hearing in February, agreed the police department’s tolerance of extremist cops undercuts efforts to build a stronger relationship with communities.

Taliaferro endorsed a policy that explicitly prohibits membership in certain groups and outlines which are off limits to officers.

“Our department needs to have clear rules that are void of [interpreting] it one way or another,” said Taliaferro, now chair of the Police and Fire Committee.

“If you are a member of an extremist organization that promotes violence, it promotes the overthrow of government, it promotes anything that stands contrary to our department, then you should face the disciplinary process,” he said.

A path forward?

The Community Commission for Public Safety and Accountability is working with the police department to update a longstanding policy that prohibits police officials from joining or associating with “criminal organizations,” specifically street gangs.

The most recent draft policy, submitted by the police department in September, expands the scope to bar “active participation” in both criminal and “biased” organizations that use violence to deny others’ rights, achieve ideological goals or advocate for “systematic illegal prejudice, oppression, or discrimination.”

Perhaps most notably, the draft prohibits membership in groups that “seek to overthrow, destroy, or alter the form of government of the United States by unconstitutional means.”

Cops could face discipline for recruiting members to an organization, attending an event, raising money and making contributions, or even engaging with a banned group’s content on social media.

Organizations would be identified by the police department’s bureau of counterterrorism, but the list would be kept from the public, under the draft.

In an interview, Remel Terry, a commissioner on the civilian-led panel, said the commission has urged the department to publicly release a version of the list that includes the names of widely known extremist organizations while also scrutinizing officers who engage with groups that may “fly under the radar.”

“One of the finer points that we’re trying to put on the policy is to make sure that reliance on the list is clearly secondary to the assessment of conduct,” added Commissioner Yvette Loizon.

As a panel with broad oversight powers, the commission has asked for an updated list of extremist groups and criminal organizations every three months, along with data on the number of relevant complaints against officers, how many are sustained and how cops are disciplined.

Commissioners have not announced a date to vote on the draft policy. But Loizon said she and other commissioners have already been getting input from Chicagoans, including those on the police force.

“I think it’s really important to emphasize that when we talk about how huge of an issue this is, we tend to focus on community because that’s our bread and butter as community commissioners,” she said. “But we’ve heard the same feedback from Chicago police officers who don’t want to see people with these bias-based beliefs within their ranks.”

‘Who gets to decide?’

John Catanzara, president of the Chicago Fraternal Order of Police, said his powerful union doesn’t condone extremism and acknowledged “there’s things officers should be disqualified over,” like trying to overthrow the government or engaging in other illegal activity.

But he said the investigations of cops linked to the far-right have gone too far, slamming Witzburg for repeatedly pressuring police officials to reopen cases.

“All of this is a witch hunt, a broad brush,” he said. “And it just needs to stop.”

He complained that the police union has so far been “kept in the dark” as the new policy has been hashed out and expressed concern that officers could face discipline based solely on their prior affiliations. He questioned how groups will be deemed off limits.

“Who gets to decide what are the organizations that qualify for the bad boy list or bad girl list?” he said. “It feels like it should be a much more encompassing conversation about what we believe we wouldn’t want our members to also be part of.”

For Catanzara, allegations of extremism hit close to home. He faced criticism for posing with a white supremacist at a downtown rally and later retired from the police department while facing disciplinary charges for making obscene and inflammatory social media posts. Still, he stood by his record as a cop and said other officers should be judged similarly.

“You can categorize me and label me any way you want,” he said in an interview with a reporter. “But you show me how any of those accusations ever translated into a complaint by a citizen on the street that I mistreated them because of a certain thing. It never, ever happened.”

‘More willing to protect their own’

Tischauser, from the Southern Poverty Law Center, said the police department’s past efforts to address extremism among officers appear to be rooted in public relations instead of holding officers accountable.

He blamed a “flawed” culture that is “more willing to protect their own than protect communities.”

“In my work nationally talking to policymakers, it is difficult to get them to acknowledge the problem,” he said. “It is usually the result of tragedy. It is usually the result of someone being harmed.”

In January, Tischauser sent a scathing letter to Brown and then-Mayor Lori Lightfoot slamming the police department’s decision to allow Bakker to keep his job. He noted that some federal and state officials have developed tough policies tackling extremism.

The U.S. Defense Department bars active service members from engaging in extremist activities, which the department acknowledged damages trust and confidence in “the military as a professional fighting force.”

President Joe Biden signed an executive order requiring the U.S. Office of Personnel Management to establish best practices to “help avoid the hiring and retention of law enforcement officers who promote unlawful violence, white supremacy or other bias.”

In Washington state, the administrative code was expanded to deny or suspend a police officer’s certification due to “affiliation with one or more extremist organizations.”

Chicago’s new police superintendent said he favored the proposal to create a list of specific hate or anti-government groups that officers could not join.

“When we know that we have someone who could ruin those relationships with our community members through discriminatory behavior, we need to step up immediately,” Snelling said.

“People like that need to be removed from the department.”

Tom Schuba covers police for the Sun-Times. Dan Mihalopoulos is an investigative reporter on WBEZ’s Government & Politics Team.