It wasn’t just determination and hard yakka that built Australia’s prosperity. It was unpaid, coercive and forced labour off the backs of black workers.

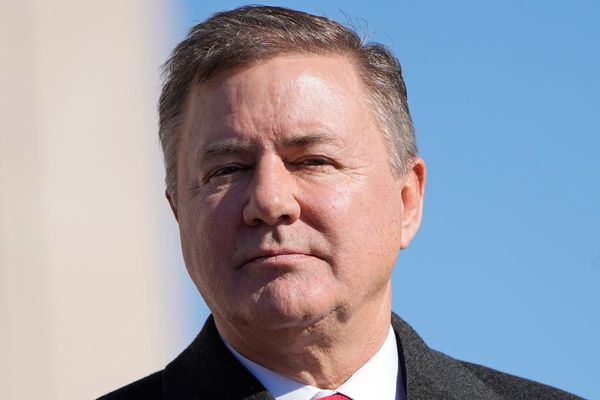

Australia’s history of slavery is — as Prime Minister Scott Morrison made apparent yesterday — poorly understood and often denied. (The PM has today apologised and sought to clarify his statement.)

But the fact is, either through slavery, servitude, exploitation or stolen wages, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders — and men kidnapped from Melanesia — played a massive role in developing Australia into the wealthy country it is today.

Why the confusion?

One of the reasons for denial of Australia’s dark past was due to the legal definitions around slavery, says Monash University law professor and Castan Centre for Human Rights associate Dr Stephen Gray.

Slavery was legally abolished in 1833 in most British colonies — though the illegal slave trade was often ignored by authorities.

“Some people have debated whether what happened with Indigenous people qualified as slavery as it wasn’t actually legal,” he told Crikey. Critics argue retrospectively applying the modern United Nations definition of slavery to Australia’s history isn’t fair.

“[But] there was a body of opinion back then that what was happening was slavery. The picture shows people understood what it was,” Gray said.

For example, a newspaper excerpt from 1863 details the “first time [Queenslanders] were made aware that the slave trade had commenced”, referencing a “cargo of miserable wretches”.

“Roving stockmen driving parties of miners would get hold of Indigenous people and keep them as slaves,” Gray said.

Importantly, the definition of slavery is rubbery: “Australia’s history is not just slavery. It’s servitude and exploitation and stolen wages and stolen trust funds,” he said.

Often Indigenous people were exploited on a large scale through limited payment and no freedom of mobility.

How did slavery and exploitation contribute to the economy?

From domestic servants and sex slaves on cattle farms and cane fields, Australia’s pastoral land developed largely thanks to the exploitation of the Indigenous population.

Slaves were widely imported by Robert Towns, one of the most prolific “blackbirders” in Australian history. He has a statue in Townsville, the city which bears his name. Towns imported “many hundreds” of so-called “savages” from Melanesia, often through kidnapping and coercion.

His reasoning? “I came to the conclusion that cotton-growing upon a large scale either must be abandoned in Queensland, or be carried out by cheaper labour,” he wrote in a letter to the colonial secretary of Queensland in 1863.

His huge and profitable estate in Logan had its own cotton gin, sawmill and a small hospital.

Elsewhere, the Vestey family made its fortune in cattle farms at Wave Hill station in the Northern Territory. The family more than doubled its yield across 10 years in the 1800s, with entire families of the Indigenous Gurindji people working for rations.

A report from 1946 found those on the farm lived in squalor and were exposed to sexual abuse, child labour and unsafe drinking water.

Mistreatment of locals, along with anger over stolen land, led to the famous 1966 Wave Hill Walk-Off.

The Vastey family business is still going strong today.

But Australia’s slavery profits go back even further, says University of NSW professor of international and political studies Clinton Fernandes.

“The single largest destination of British foreign investment throughout the second half of the 19th century was Australia,” he said. The British government invested in pastoral development, the wealth of which “came out of exported colonies, through indentured labour”.

Colonist landowners would collect tax. Those unable to pay tax would be forced to work off their debt on farms — the proceeds of which would be reinvested into Australia.

“The slave trade created the basis for capital ascent in the west in Europe. It profited off and created the basis for its rise,” Fernandes told Crikey.

Why is this still not widely known?

Industry professor at Jumbunna Institute of Education and Research Nareen Young told Crikey that little of this history is taught in schools.

“I’d certainly like to see the history of the establishment of the pastoral industry, and all of the agricultural industries, taught in schools,” she said. “The loss of land and exclusion from the employment market is obviously the reason for the ‘wealth gap’ we see today.”

While a lot of Australia’s knowledge centres around the Northern Territory, Young said that Indigenous history and exploitation needed to be expanded to all states.

“For the PM not to understand the history — it speaks to the need for truth-telling. For the truth to be part of the national narrative,” she said.

Is the Australian public ignorant when it comes to the history of exploitation in our country? Let us know your thoughts by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication in Crikey’s Your Say section.