Daniel Boyd’s solo exhibition Treasure Island, now on at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, is a deeply political and personal interrogation of Australia’s colonial history.

Boyd is a Kudjala, Ghungalu, Wangerriburra, Wakka Wakka, Gubbi Gubbi, Kuku Yalanji, Yuggera and Bundjalung man, with ni-Vanuatu heritage. His work knocks over the apple cart of accepted white Australian history and presents the tumbled mess of bruised fruit.

For many, the true tales of racism, exploitation and violence towards First Nations people in Australia will not be a surprise, but Boyd charges the data with emotion and affect.

One of the featured artworks presents a large Aboriginal map showing multiple language group areas, and with the words “Treasure Island” across its flank. This refers to the imperial notion of Australia as Terra Nullius, a land of free resources to steal or extract.

Drawing on iconic tales of Robert Louis Stevenson (author of Treasure Island and collector of what Boyd describes as “Pacific fetish objects”) and countless ethnographic images from archives, Boyd creates his disruptions.

The works on display reflect the range of Boyd’s critical inquiry into the cosmos, patterned navigational maps, Plato’s cave allegory and dark matter in space and history.

The transference of knowledge

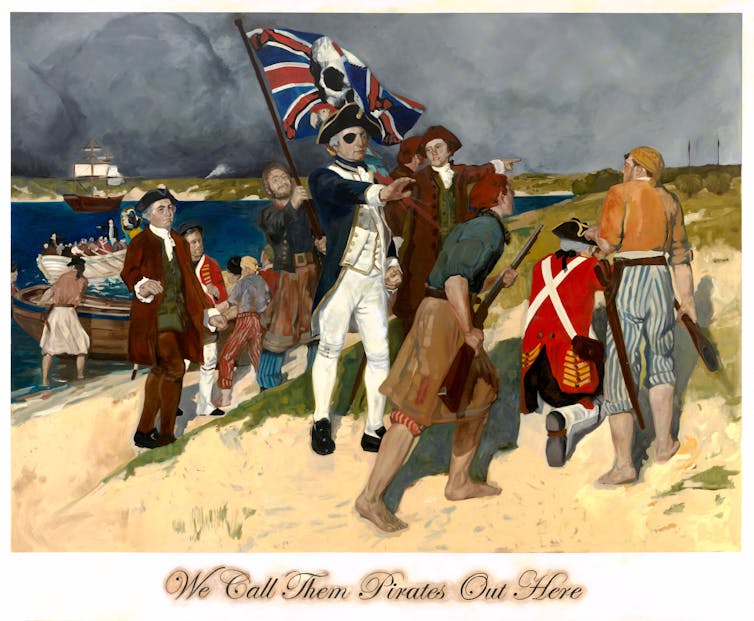

We Call Them Pirates Out Here (2006) presents the viewer with a familiar image of Cook’s first landing at Kamay (Botony Bay), in 1770. Boyd re-presents Cook as a pirate, unlawfully stealing unceded land.

In Boyd’s hands the scene becomes chaotic rather than messianic. But the stain of power is still there.

The false truth can be disrupted, but the violence has already been done. De-colonialism has not yet been achieved.

Read more: Terra nullius interruptus: Captain James Cook and absent presence in First Nations art

I asked Daniel Boyd if non-Indigenous people will ever be able to understand life in the same way that First Nations people do – as multiple and complex, as holistic and connected and as poetic? He replied:

when Indigenous people situate themselves with place, with the sea, the land and the sky, then that knowledge can be transferred.

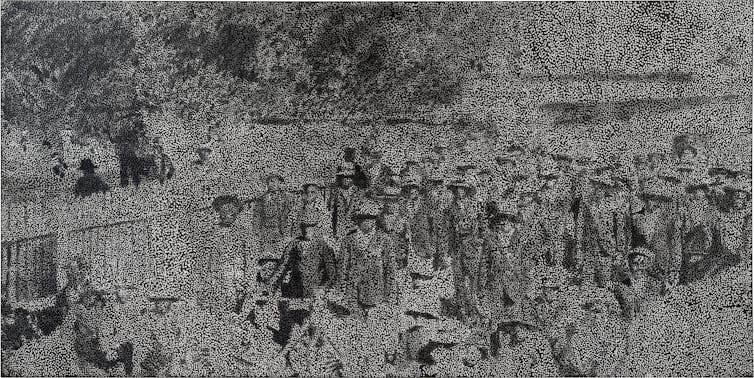

Boyd’s exhibition is exactly that transference of knowledge to audiences. He presents a middle room of artworks dedicated to the period of “blackbirding” in Australia, where people from South Sea Islands were brought to Queensland as slave labour to work on sugarcane plantations.

Boyd tells me that his own great-great-grandfather Samuel Pentecost was forcibly taken from Malakula Island, Vanuatu, and brought to Queensland to work for no pay.

On the backs of slaves

In Secret Cures of Slaves, historian Londa Schiebinger writes about slaves being tossed into mass graves at the end of cotton or sugarcane rows if they died from exhaustion or malnutrition on site. I’ve read of slaves being only fed bananas or dumb cane which made their tongues swell and stopped verbal backlash.

As Boyd tells me, the Queensland economy was built on the backbone of free labour of First Nations and Pacific Island peoples. Wages were stolen and people were exploited.

Along with domestic servitude, this free labour created capital and profit for generations of white Australians.

Boyd continues these disturbing tales with a painting of an imperial ship, full of produce. The artist tells me that Joseph Banks “discovered” Tahitian breadfruit as a useful species to feed to plantation slaves, so the breadfruit was transported aboard the Bounty ship to Jamaica, another site of plantation slavery.

The brutality continued through Australian history and in Boyd’s own family lineage. Samuel’s son, Boyd’s great-grandfather, was stolen from his parents up in Mossman Gorge and taken to Yarrabah Mission.

Boyd transfers an image of Harry Mossman, photographed by anthropologist Norman Tindale, for this exhibition. This is one of the most unadorned and plain portraits of the exhibition: it has a calm, proud and direct appeal.

Adjusting our focus

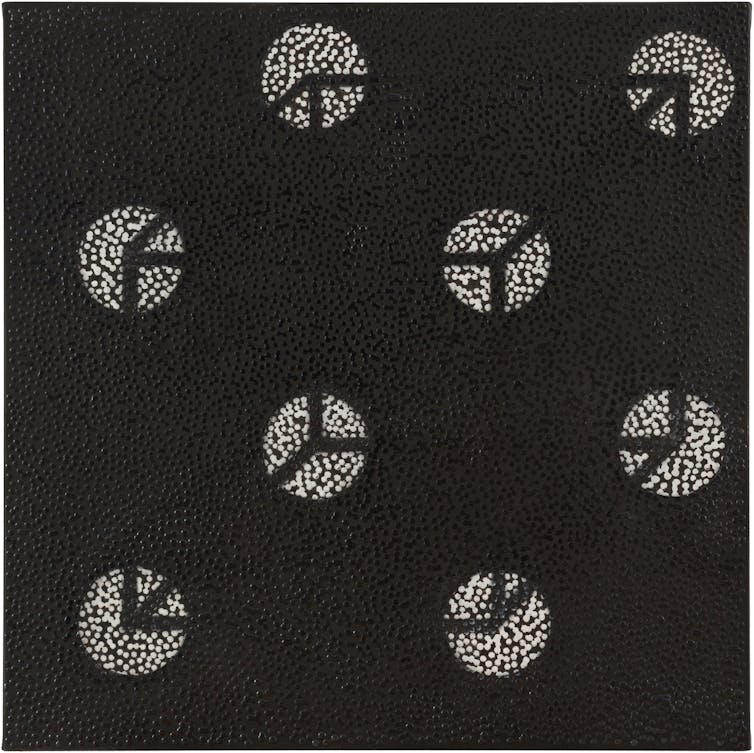

Boyd’s use of tiny glue dots on the surface of his artworks references traditional painting but also acts as lenses. These adjust our focus and help us see the true stories, painful and sorrowful and shameful as they are.

They are emblematic of the way light (western knowledge) can blind us from what we need to see (Black truth). The mostly white dots are portals to better see the hidden stories.

Boyd’s art dispels white Australian propaganda that erases information about slavery, the stolen generation and the early years of white settlement. He encourages audiences to see the true stories lurking in the shadows.

It’s not easy, but facing the truth is the first step to decolonising our Australian history.

Daniel Boyd Treasure Island is at the Art Gallery of New South Wales until January 2023.

Prudence Gibson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.