I’ve been obsessing about an old banker’s box. It’s tucked away in a spare bedroom. There isn’t much in it: some punk rock posters, letters, photographs of a long-closed homeless shelter, and a handwritten diary. After decades of disinterest in the box, I find myself seeking it out, particularly the diary. Hoping that it can help me make sense of what is happening in the world around me.

The fact is, I just can’t seem to get my bearings. I search for signposts and familiar patterns, but it’s like looking through the distortions of a funhouse mirror. My political, social, and environmental certainties have been knocked off their axes. The world is in uncharted territory. These are troubled times. Disorienting times. Frightening times. Blame it on the fire tornados or the COVID-19 pandemic or the data-driven AI that is poisoning the well of human conversation. Blame it on toxic capitalism.

I know many in my age group (Generation X and boomers) who are also increasingly obsessed with their younger lives. Nostalgia for the 1980s is everywhere. In popular culture, the ’80s have become shorthand for a simpler and more fun time—A Flock of Seagulls hairstyles, catchy pop songs, and Breakfast Club brat pack tropes. It is Hawkins, Indiana, in the Netflix hit Stranger Things—a landscape of well-stocked shopping malls, morning paper routes, and social cohesion. In Hawkins, the youth stand up to the darker forces threatening middle-class America—an “upside down” world of monstrous Demogorgons. Airbrushed with ’80s nostalgia is the real Upside Down that confronted people—the political and corporate counterrevolution that killed the American dream. This is what brings me back to the banker’s box. Not nostalgia. I am looking for clues. I want to know how that Upside Down created the dystopian world confronting us today.

The obsession with the ’80s isn’t new. There has long been a superficial fixation on the era. In Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America, Kurt Andersen writes, “We [aren’t] experiencing ‘an eighties revival’ . . . in fact the ‘eighties never ended’ . . . the character of the American 1980s [was] ‘manic, moneyed, celebrity obsessed.’ None of that really changed in the 1990s or in the 2000s or in the 2010s.”

But the crisis of the 2020s is something different than a lingering cultural stasis. The reality is that the political, environmental, and economic forces unleashed in the 1980s have finally caught up to us.

As 1980 dawned, I had a simple plan—quit school, play in a band, and get a job. Except, in 1980, there weren’t many jobs out there. The older brothers of some of my friends said that the best way to make good money was to get hired at a factory or warehouse. The suburbs of Toronto were built around a multitude of industrial operations, such as the General Motors van plant and the numerous factories along Scarborough’s Golden Mile. But those factories weren’t hiring. Many were closing.

Since the mid-1970s, Toronto had been undergoing a major wave of deindustrialization as garment factories, slaughterhouses, and warehouses closed. Empty factories and warehouses dotted the neighbourhoods of Riverdale, the Junction, Liberty Village, and the garment district along Spadina Avenue. Blue-collar Toronto was disappearing, and this led to a plethora of opportunities for young artists to renovate loft spaces.

I was anxious to get out of my parents’ house in Scarborough and join this exciting world that was emerging. But the only jobs to be had were washing dishes or taking dodgy commission gigs hustling magazine subscriptions and vacuum cleaners door to door. There was no point calling the want ads. Nobody ever called back. So I put on a skinny black tie and went downtown, stopping in at every restaurant and shop to ask if they were hiring. This went on for weeks.

I didn’t comprehend that I was coming of age during the bleakest economic crisis since the Great Depression. It was bad across Canada and even worse in the United States, where a huge number of steel mills, garment factories, and manufacturing plants closed. Millions of well-paid union jobs were gone forever. The crisis created a panicked race to the bottom as workers who were still hanging on were given the untenable option of accepting wage cuts and the erosion of benefits or seeing their employment disappear altogether.

But there was a major difference between the job crisis of 1980 and the Great Depression. In 1929, the world was hit by an unexpected economic collapse that defied the understanding of politicians and economists. In 1980, however, the economic shock was planned at the highest level, and it had the fingerprints of Milton Friedman all over it.

You can name all the people who personified the excess or the austerity of the 1980s—Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, Madonna—but it was Friedman who defined the era. On January 1, 1980, he and his wife, Rose Friedman, released a provocative manifesto called Free to Choose: A Personal Statement. A little more than a week later, he followed it up with the launch of a syndicated weekly television series extolling his simple message: government is bad; capitalism is good. Get government out of the way and the natural order of the universe will be restored by the magical “invisible hand” of the market. It was a form of economic fundamentalism based on the pseudo-scientific claim that an economy driven solely by greed and those with the most money is the natural order.

Friedman was the key spokesperson for the Chicago School, a group of counterrevolutionaries—and members of the economics department at the University of Chicago—who pushed this fundamentalism to its hardest conclusion. They openly challenged the economic consensus on which the post–World War II economy had been based: that a balance of public and private interest was essential for creating a prosperous society. Instead, they argued that the only business of business was to make as much money as possible, with none of the hindrances of social responsibility. Democratically elected governments needed to be limited to the function of providing tax breaks for the wealthy while cutting public spending and stripping regulations.

This was a total repudiation of the factors that had made the great economic miracle of postwar North America possible. The American labour movement tagged the birth of the twentieth-century middle class to the famous sit-down strike by auto workers in Flint, Michigan, in 1936/37. The strike galvanized workers across the country and signalled an end to the days when the working class would accept precarious employment and low wages. The subsequent union victories were backed up by the progressive idealism of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal, which put in place a slate of public programs to guard against a repetition of the economic disaster of the Great Depression. The improvements for blue-collar workers could be easily measured—strong wages and solid pension plans. The working class achieved unprecedented social mobility as workers gained the ability to own a house, send their children to university, and retire with dignity.

The postwar era represented the golden age of American life and social advancement, but Friedman derided this economic miracle as the road to “tyranny and misery.” His attack on the New Deal, government investment, and workers’ rights made him a fringe economic figure for much of the 1960s and early ’70s. But in 1975, Friedman was given a chance to try out his theories when he was invited to give advice to Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet. It is ironic that Friedman’s experiments in “economic freedom” were undertaken against a backdrop of brutal repression and terror that came in the wake of a CIA-manufactured coup. And the experiments didn’t go well. Under Friedman’s direction, Chile’s economy went into free fall. Inflation spiralled to 375 percent, and more than 177,000 jobs were lost in the manufacturing sector between 1974 and 1983. Both the middle and working classes suffered a huge loss of economic stability.

Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volcker laid out the strategy: “The standard of living of the average worker has to decline.”

The Chilean upper class, however, viewed Friedman as a miracle worker, because his economic policies resulted in a massive transfer of public assets into the hands of the super wealthy. In her book The Shock Doctrine, Naomi Klein writes: “Chile never was the laboratory of ‘pure’ free markets that its cheerleaders claimed. Instead, it was a country where a small elite leapt from wealthy to super-rich in extremely short order—a highly profitable formula bankrolled by debt and heavily subsidized (then bailed out) by public funds. . . . Chile under Chicago School rule was offering a glimpse of the future of the global economy . . . a huge transfer of wealth from public to private hands, followed by a huge transfer of private debts into public hands.”

Friedman saw an opportunity to import these extreme methods to the United States. The New Deal co-operation between labour, big business, and government had been severely weakened by inflation, economic stagnation, and the dramatic energy price shocks that came as a result of the 1973 Arab–Israeli war. On top of this, North American manufacturing was being forced to contend with Asian competition, and they were losing. By the late 1970s, there were a number of corporate leaders and politicians, such as Ronald Reagan, who thought the United States was ready for the Friedman touch. “The tide is turning,” Friedman wrote in his January 1980 manifesto. “In the United States, in Great Britain, the countries of Western Europe . . . there is growing recognition of the dangers of big government. . . . It is becoming politically profitable for our representatives to sing a different tune.”

Friedman’s disciples knew full well that any attempt to introduce the Chilean “miracle” to the United States would face significant social and political resistance. Their solution was audacious. They wanted to force an economic crisis of the magnitude of the Great Depression so that workers would have no choice but to accept the Friedman solution. The proposal was put forward by Friedrich Hayek, founding father of the Chicago School. Writing in the New York Times, he promoted the notion of engineering an economic collapse to create wage insecurity and restore the power of capital. He derided American politicians for being too “afraid” to take such an obviously destructive approach.

But there were those in power who saw the brutal efficacy of Hayek’s proposal, and the plan was put into action, in two phases, by Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volcker. The first was an initial interest rate spike to 13 percent that hit hard in January 1980. This sudden increase caused the economy to stumble badly and led to a massive loss of jobs. Volcker followed up with an even more severe shock in 1981, when he drove rates above 21 percent. The American economy went into a tailspin. People stopped purchasing vehicles and appliances. Families defaulted on their mortgages. Small and mid-size companies were hollowed out and left as easy pickings for the emerging face of mercenary capitalism—the corporate raider.

Volcker knew exactly what he was doing. Speaking before Congress, he laid out the strategy: “The standard of living of the average worker has to decline.” Volcker’s move was a punch in the face to unsuspecting blue-collar America. In his book Reaganland, Rick Perlstein notes that “elite opinion was largely ecstatic” about the “radical shock treatment” being used to teach American workers their true place.

But interest rate hikes were only the first part of this shock to the system. The second was political. And unionized workers were completely unprepared for the destructive forces that were suddenly being turned on them.

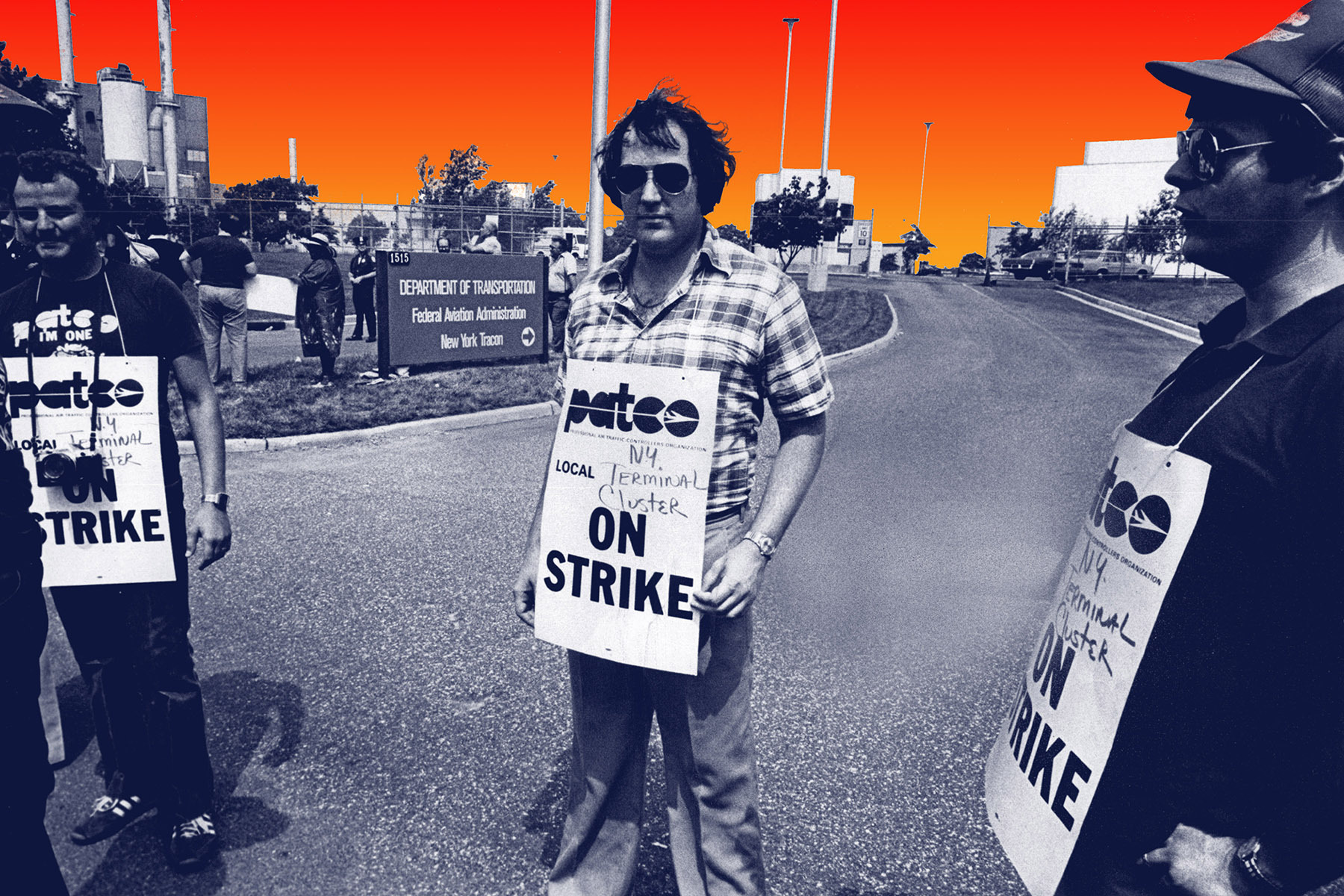

In 1981, the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization went on strike. Newly elected President Reagan gave them a two-day ultimatum to return to work. He then fired more than 11,000 of these highly skilled workers in a single shot and blacklisted them permanently from being hired by the federal government. The union movement was staggered by Reagan’s harsh penalty. Nothing like this had been done in the postwar world. Volcker was impressed. He believed that Reagan’s decision to publicly destroy such a powerful union was the most significant move in the battle to bring the working class to heel. The obliteration of the union was a signal to corporate America to begin the rollbacks of wages, security, and benefits—launching a full-scale attack on the unionized workforce.

These attacks on workers’ security took place amid widespread job losses. In 1980, more than 188,000 jobs evaporated at auto plants for the big three—GM, Ford, and Chrysler. The hit to the American steel industry was equally traumatic. It had begun in the late 1970s, when steel mills began to close across the United States.

What was happening to workers across the country could be called “Operation Break the Working Class.” It was a broad policy to undermine worker confidence by destroying the capacity of organized labour to offer resistance. This took place in tandem with a large transfer of wealth to the financial elite. Reagan’s first budget represented a giveaway of more than $750 billion to the super rich in a mere five years. This drove federal debt to $2.8 trillion and turned the United States into the world’s largest debtor nation. At the same time, Reagan cut basic services to the underclass, such as the food stamps program.

But the lasting impact of “Reaganomics” came from the full-scale attack on the regulations and protections that had maintained the economic balance in postwar America. Key to this was stripping the oversight governing America’s financial and banking sector. The result was a flurry of high-risk borrowing and speculation. It brought an unprecedented flood of wealth to financiers, but the working and middle classes paid the price. The market was soon flooded with junk bonds and risky debt leveraging that led to a series of financial disasters.

The Savings and Loans Crisis of the late 1980s was a direct result of this casino economy. Banking deregulation had created a culture of increasingly reckless financial speculation in the historically prudent savings and loans industry. In a few short years, the industry suffered an unprecedented collapse that wiped out a third of the institutions where millions of Americans held their mortgages and family savings. Taxpayers were stuck with paying a $132 billion bailout to cover the collapse.

This was nothing compared to the 2007–2010 subprime mortgage crisis that obliterated the savings and homeownership of millions. This later crisis can be directly traced to a Reagan-era scheme that allowed speculators to gamble and offload bad debt in the form of a derivative known as a credit default swap.

Looking back more than forty years, we can see how the Reagan/Friedman counterrevolution dramatically altered the entire social, economic, and political landscape of the United States. As author William Kleinknecht writes: “The bitter legacy of Reaganism—the subprime mortgage scandal, the near collapse of the financial system, widening income inequality, the emergence of Lockdown America, the obscene inflation of CEO compensation, the end of locally owned media, market crashes, blackouts, drug company scandals, rampant greed and materialism—is all around us.”

Such clarity is often obscured amid the toxic political rhetoric and disinformation of a nation increasingly defined by red state/blue state culture wars. And the statistical data is indisputable. Across all economic indices, American workers have faced a shocking level of lost opportunities over the past four decades. A 2020 study by the Rand Corporation, undertaken to identify the links between economic disparity and the political instability of American life in the twenty-first century, found massive losses to workers since 1980. For example, in 2018, a working-class Black man was making $26,000 (US) a year less than what he would have been paid if the income patterns prior to 1980 had held constant. A college-educated worker earned between $48,000 and $63,000 (US) a year less.

The authors of the Rand report tracked these lost wages, as a direct conduit, to the bank accounts of the 1 percent. They valued the loss of income for every worker at $1,144 (US) a month for every year over the past four decades. The final price tag for this looting of the American worker comes to $50 trillion (US) in accumulated lost wages and benefits.

There is nothing natural about this wage theft. Operation Break the Working Class has created a generation of billionaire oligarchs from the stolen wages of the American working class.

As Stephen Stoll writes, “Seeing the world without the past would be like visiting a city after a devastating hurricane and declaring that the people there have always lived in ruins.”

The 1980s were the hurricane. The hurricane’s path has been difficult to track because many of the most damaging impacts took decades to play out—more like a slow-moving disaster. But the hurricane has finally touched down, and we are picking up the pieces in real time. We are being forced to confront the great lies of the era that have cast a shadow over the past forty years: that an international race to the bottom was the natural order of the universe; that cities would become more livable if we turned our neighbourhoods over to capitalist speculators. And the great petroleum-driven lie that assured us that dealing with the climate crisis could be put off for another day.

To find our way out of this mess, it is necessary to confront the false history of the 1980s. Historical amnesia is not accidental—it is a political construct. If you scratch the sheen of ’80s nostalgia, the underlying socio-economic fractures are readily apparent. These contradictions in the popularized narrative constitute a dangerous memory. As theology professor Candace McLean at the University of Portland explains, “Dangerous memories . . . are the subversive memories of the victims of history. . . . They are dangerous to those in positions of power because they are the seeds of resistance and change . . . and hope to the marginalized.”

Excerpted from Dangerous Memory: Coming of Age in the Decade of Greed by Charlie Angus, 2024, published by House of Anansi. Reprinted with permission from the publisher.