Some species go extinct twice – one time when the last individual stops breathing, and a second time when our collective memory about the species disappears

© Copyright by GrrlScientist | @GrrlScientist | hosted by Forbes

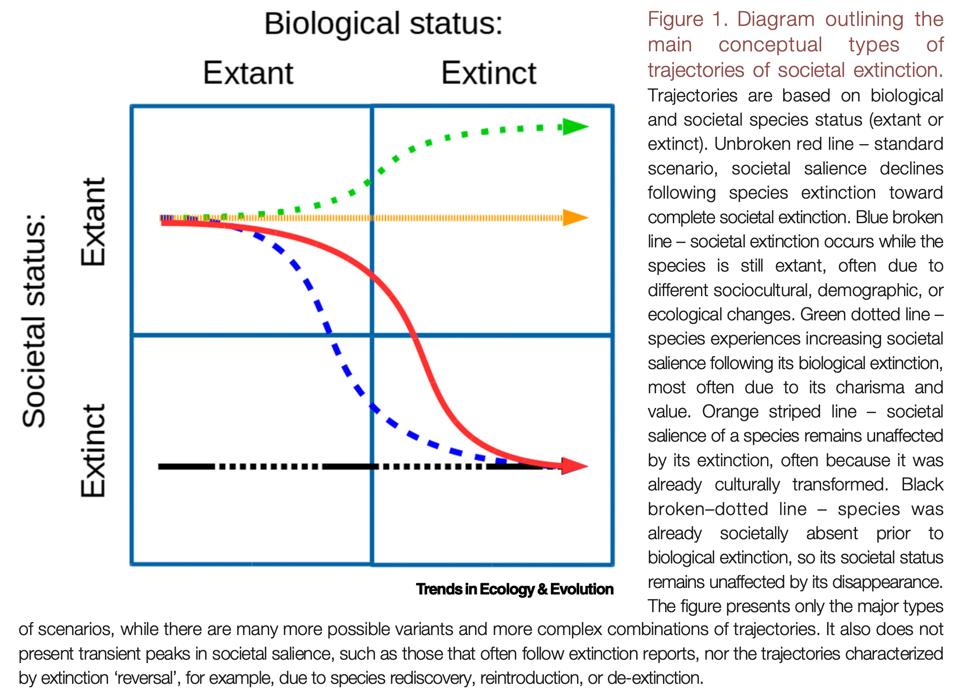

An international team of scientists recently published a study arguing that species can go extinct twice: there is the biological extinction event, that tragic moment when the last member of a species lives no more, but there’s also societal extinction, which occurs when that species is expunged from our collective memory and cultural knowledge. Species can disappear from our societies, cultures, and even our consciousness at the same time as, or even before, human actions push them over the edge into oblivion.

Similar to biological extinction, societal extinction can have serious conservation consequences.

“[J]ust as population declines may lead to biological extinction, the decline of collective attention and memory may lead to the societal extinction of species, which can seriously affect conservation efforts”, said conservation biologist Ivan Jarić, lead author of the study and a researcher Biology Centre of the Czech Academy of Sciences.

Together with his collaborators, Dr Jarić found that societal extinction depends upon a variety of factors, including the species’ charisma, its symbolic or cultural value, whether and how long ago it went extinct, and how distant and isolated its range is from humans.

Societal extinction, as a phenomenon, has been noted before and remarked upon in the scientific literature. For example, communities in southwestern China and indigenous peoples in Bolivia were found to have lost their local knowledge and memory of extinct bird species (ref & ref).

“Such loss of memory got to the point where people were unable to even name those species, and didn’t remember what those species looked like, or their songs”, ecologist Uri Roll, co-author of the study and senior lecturer at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, said in a statement. “Similarly, the extinct Japanese wolf, okami, has only a few specimens that can be found in museums nowadays, which challenges memory of the species within Japanese society.”

Also known as the Honshū wolf, Canis lupus hodophilax, the Japanese wolf was officially declared extinct in 1905. It was a subspecies of gray wolf that was found only on the islands of Honshū, Shikoku and Kyūshū in the Japanese archipelago. It was only recently realized that this animal was the last living member of the Pleistocene lineage of gray wolf (ref) — and it may also have been the closest wild relative to the domestic dog.

Some species defy the fate of societal extinction, however. What makes them special in this regard?

“Species can also remain collectively known and salient after they become extinct, or even become more popular”, another co-author, ecologist Ricardo Correia, who is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Helsinki, said in a statement.

“However, our awareness and memory of such species gradually becomes transformed, and often becomes inaccurate, stylized or simplified, and disassociated from the actual species”.

One of the more disturbing examples of disassociated or inaccurate ideas about an extinct species, in my opinion, is the situation faced by Spix’s little blue macaw, Cyanopsitta spixii. This small macaw was declared Extinct In The Wild in 2018 (more here), although approximately 100 individuals still exist, but only in captivity. Yet, despite its relatively recent extirpation, a report (only in Portuguese) found that school children who live in the Curaçá municipality of Brazil, which is part of this parrot’s former range, erroneously think this species is found in Rio de Janeiro, because of its appearance in the animated film, Rio.

But in contrast to the Spix’s macaw, most species never have the opportunity to become societally extinct because most people may never have been aware of them in the first place.

“This is common in uncharismatic, small, cryptic, or inaccessible species, especially among invertebrates, plants, fungi and microorganisms — many of which are not yet formally described by scientists or known by humankind”, Dr Roll said. “They suffer declines and extinctions in silence, unseen by the people and societies.”

Why should we care about societal extinction?

“Forgetting species that used to be present in our surroundings can affect our perception of the environment and what we expect its natural state to be, such as what is a normal or healthy environment, and thus leads to a shifting baseline syndrome”, Dr Jarić explained in email.

Shifting baseline syndrome describes the psychological and sociological phenomenon whereby people constantly lower their thresholds for accepted environmental conditions. In the absence of past information or experience with historical conditions, each new generation accepts the increasingly impoverished situation into which they are born and raised as being normal (ref).

“Not being aware that species were there and have since gone [extinct] can produce a false perception of the severity of threats to biodiversity, leading us to underestimate true extinction rates”, Dr Jarić explained in email. “It can reduce our will to pursue ambitious conservation goals. For example, it could reduce public support for rewilding efforts, especially if such species are no longer present in our memory as natural parts of the ecosystem.”

One especially notable rewilding effort in the United States is the reintroduction of the gray wolf, Canis lupus, to Yellowstone National Park by the USFWS after their extirpation 70 years before (more here). This successful rewilding effort allowed shrubs and trees, especially young willow, aspen and cottonwood, that were formerly eaten to the ground by wapiti (elk) and deer, to grow. As the native flora became re-established, biodiversity increased due to the expanded availability of food and shelter provided by the growing variety of plants and animals. Remarkably, with the arrival of wolves, beavers rebounded because it turns out that they, like wapiti, eat young willow trees. Further, the presence of wolves altered the rivers themselves because riverbank erosion decreased so the rivers meandered less, the channels deepened and small pools formed — all due to recovering streamside vegetation (ref).

But none of these astounding and often unexpected improvements in Yellowstone would have happened if societal extinctions had prevented wolf rewilding efforts. Although it was never intended that wolves should save beavers, this real life experiment shows how unexpected consequences associated with societal extinctions can alter our perceptions of the environment and of species interactions.

“As more and more species disappear from our memories, there’s evidence that it alters our perception of how important it is to protect what remains”, Dr Jarić explained in email.

Worse, societal extinctions can create false perceptions of the severity of threats to biodiversity and true extinction rates, and diminish public support for conservation and restoration efforts — like the reintroduction of wolves into Yellowstone, for example.

“[J]ust as population declines may lead to biological extinction, the decline of collective attention and memory may lead to the societal extinction of species, which can seriously affect conservation efforts.”

To counteract societal extinction, Dr Jarić and his collaborators emphasized the importance of targeted, long-term marketing campaigns and conservation education to revive, improve, and maintain our collective memory of societally extinct species.

Source:

Ivan Jarić, Uri Roll, Marino Bonaiuto, Barry W. Brook, Franck Courchamp, Josh A. Firth, Kevin J. Gaston, Tina Heger, Jonathan M. Jeschke, Richard J. Ladle, Yves Meinard, David L. Roberts, Kate Sherren, Masashi Soga, Andrea Soriano-Redondo, Diogo Veríssimo, and Ricardo A. Correia (2022). Societal extinction of species, Trends in Ecology and Evolution | doi:10.1016/j.tree.2021.12.011

26a8b4067816acd2da72f558fddc8dcfd5bed0cef52b4ee7357f679776e6c25d

NOTE: This piece is © Copyright by GrrlScientist. Unless otherwise stated, all material hosted by Forbes on this Forbes website is © copyright GrrlScientist. No individual or entity is permitted to copy, publish, commercially use or to claim authorship of any information contained on this Forbes website without the express written permission of GrrlScientist.