Inflation rates have become almost impossible to ignore. In the UK, inflation has soared in recent months, now reaching 9% – the highest rate for 40 years. The Bank of England expects it to rise to 10% this year and for the economy to slow down.

Increasing prices have led to a severe cost of living crisis, as wage increases have not kept pace. To add to the financial pain, most households have recently been hit by tax rises.

Lower income households will be hardest hit by inflation as they spend a higher proportion of their household budget on food, housing and energy costs. And lower incomes are more common among younger age groups, who on average earn less than their older colleagues.

This article is part of Quarter Life, a series about issues affecting those of us in our twenties and thirties. From the challenges of beginning a career and taking care of our mental health, to the excitement of starting a family, adopting a pet or just making friends as an adult. The articles in this series explore the questions and bring answers as we navigate this turbulent period of life.

You may be interested in:

Rihanna and radical pregnancy fashion – how the Victorians made maternity wear boring

Student loans: would a graduate tax be a better option?

We won’t have a male contraceptive until we change our understanding of risk

In 2021, for example, the median earningsfor those aged 22-29, were £27,092 a year, compared to £34,649.16 for the 30-59 age group.

Using these figures, we can show the amount per week an average worker may be worse off. For people aged 22-29, the median income in 2021 was £521 per week. Combining inflation and an assumed wage increase of 4.5% leaves the young worker on average £24.27 a week worse off in May 2022. This is equivalent to being £1,261 worse off this year.

For some the blow will be softened by the fact that the minimum wage has been raised by 6.6% (to £9.50) for those over 23 and by 9.8% (to £9.18) for those who are 21 and 22.

Overall though, since the financial crisis of 2008, wage growth has been subdued due to the rise of the gig economy and the use of precarious labour practices such as zero-hours contracts. These tend to result in uncertainty, poor wages and (in some cases) a lack of sick pay and workplace pensions.

Triple whammy

COVID-19 has created some job opportunities, notably in sectors such as online retail and delivery services – but these again are often roles with precarious conditions attached, with that lack of certainty and low wages at their core. Evidence suggests that more than a third of gig economy workers are aged under 34, making them particularly susceptible to inflation rises.

Nor are young people still in education immune. The British government allows for university tuition fees to increase in line with inflation, meaning the cost of learning could increase dramatically for a large number of current undergraduates.

For those who have already graduated, the higher rate of inflation will increase the interest payable upon their outstanding student loans. And if they’re in a position to start looking to buy a home, they will have noticed that interest rates are rising as the Bank of England seeks to curb inflation, pushing up the costs of a mortgage.

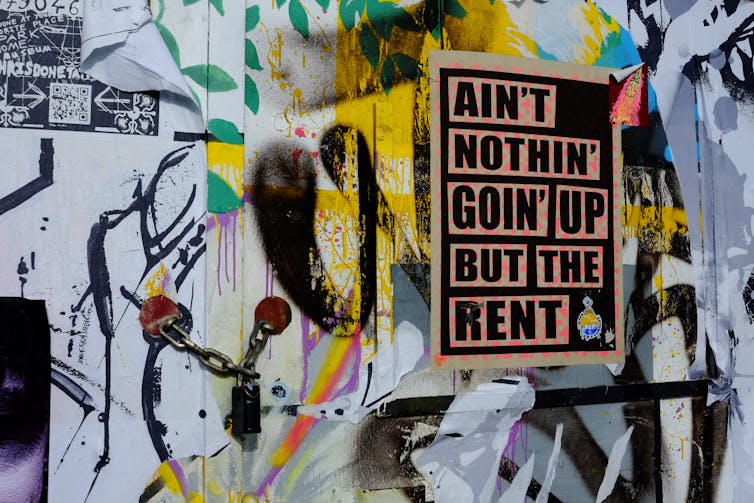

The many young people who are part of “generation rent” meanwhile, are exposed to a mixture of rising rents and decreasing disposable income. According to the education charity Intergenerational Foundation, a person in their 20s spends around half of their income on rent, energy and transport.

At the moment, all three of those expenses are rising. On average rents rose by 8.3% in 2021 to an average of £969 per month across the UK. Energy prices have seen a huge jump in recent months, and getting about just gets more and more expensive. Petrol pump prices are prohibitive for some, while rail fares are only going up. (And as fare hikes are based on inflation, future ticket prices are likely to be astronomical).

According to the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the impact of these three factors is going to lead to a fall in living standards by 2.2% in 2022-23 – the biggest slump since the 1950s. The report also suggests that it will take until 2025 for living standards to go back to pre-pandemic levels.

Meanwhile, the Bank of England and the OBR have both indicated that inflation will continue to rise until the end of 2022. If GDP growth continues to fall at the same time, the UK may be looking at a period of stagflation which would present yet another harsh economic challenge for young people, when persistent high prices would be combined with slow growth, high unemployment – and limited opportunity.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.