Changes to Australia’s isolation rules, which come into effect on Friday October 14, remove the mandate for people to isolate if they test positive for COVID.

Isolation requirements will remain for high-risk settings such as aged care, disability care, Aboriginal health care and hospitals. Workers in these sectors who can’t access paid leave while isolating will still be able to access financial support, but pandemic payments won’t be available to the rest of the population.

(Casual workers without sick leave in other sectors, however, may be eligible for state government support. Victoria, for example, offers a sick pay guarantee for up to 38 hours of work lost to illness.)

While isolation won’t be mandatory for most, it’s still important to be aware of your own infection risk and be careful around others if you test positive for COVID or have respiratory symptoms.

Should you still test?

If you’re worried you’ve been exposed to someone with the virus, or start to see symptoms, it’s always better to know your COVID status. Ignoring it can put yourself and others at risk.

Knowing you’re COVID positive is especially critical for people who are at greater risk of severe infection because they are severely immunocompromised, aged over 50 (or over 30 for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people) with two additional risk factors, or those aged 70 and above. A positive test enables people in these groups to access antivirals, which need to begin within five days of symptom onset.

À lire aussi : I have mild COVID – should I take the antiviral Paxlovid?

Antivirals can prevent an infection escalating into a severe illness or hospitalisation. A recent Israeli study of the antiviral Paxlovid found it effectively reduced COVID severity in people 65 and over infected with Omicron. Hospitalisation rates dropped from 58.9 per 100,000 days of follow-up to 14.7. This is a four-fold decrease and comparable to rates in younger adults.

If you are at-risk and have symptoms, try to get a PCR test, if possible, as this can detect an infection earlier than a rapid antigen test (RAT).

I’ve tested positive, so how long should I isolate?

The infectious period starts a day or two before symptoms and can continue for more than ten days. As time goes on, the viral load drops away, so you’re less infectious.

The general advice used to be to isolate until 48 hours after symptoms resolve. But many infections may not have obvious symptoms, and some symptoms continue after the infection, so so it’s worth monitoring using a RAT.

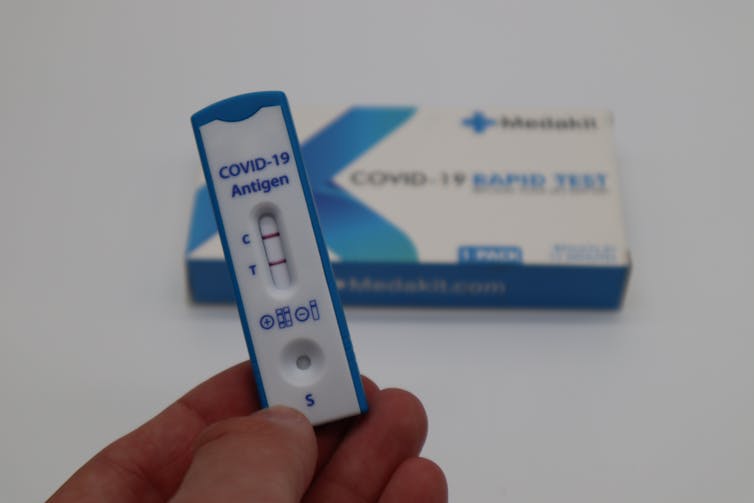

RATs perform best a few days into an infection. So while they may not pick up all infections initially, they can indicate whether you are still infectious at the end of your infection.

A recent US study of mostly young, vaccinated people concluded that for people with lingering mild symptoms, such as a persistent dry cough, a negative RAT could guide when it was safe to stop isolating. However, half those with a positive RAT didn’t appear to be infectious.

Still, it’s better to err on the side of caution if you work in high-risk settings or mix with people vulnerable to serious disease.

À lire aussi : Someone in my house has COVID. How likely am I to catch it?

Isolate while you have symptoms in summer

Symptoms remain an important way to identify risk. As we move out of the cold and flu season, there will be fewer other respiratory infections around. So coughs with fever will more likely be a sign of COVID and should be assumed so, regardless of testing.

A March 2022 UK survey reported 1,687 of 6,260 of infections, or just over one-quarter of those with known symptom status, were in people without symptoms. What’s more, 1,343 people tested positive who did have symptoms, but did not have typical COVID symptoms. So, just under half of the infections detected in this study might not have been recognised as COVID infections without testing.

Due to high rates of vaccination and previous infection, a larger proportion of people with COVID may be asymptomatic rather than having tell-tale symptoms.

Monitoring for COVID symptoms will therefore not identify all infections. So take care, especially when around vulnerable people

Masks work when Omicron exposure risk is high

In the UK during Delta and the Omicron BA.1 waves, surveys of randomly selected participants reported 13–36% higher infections rates in people who said they only sometimes wore masks (4.3%) or rarely wore them (5.2%) compared with those who said they always wore masks (3.8%).

This gap diminished after the Omicron BA.1 peak, as infections declined.

But masks do help reduce the risk of infection with Omicron, especially when infection rates are high.

So when you’re in crowded indoor spaces such as public transport, it’s best to assume the virus is present and mask up.

À lire aussi : How to wear a mask in the heat

Why avoid infection? Long COVID can be debilitating

Although things have improved in terms of severe acute disease, minimising risk of infection remains important given the risk of long COVID, which can be debilitating for some, even after mild infections.

Among Omicron infections, 4.5% of 56,003 people experienced long COVID. This compares with 10.8% of 41,361 Delta cases.

However, vaccination reduces the risk. Studies show vaccinated people are 60% less likely to develop long COVID than unvaccinated people, and 70% less likely after a booster dose.

COVID is here to stay

The removal of isolation mandates does not mean we ignore COVID, or stop isolating, or give up managing the risk we might pose to others. It will take ongoing efforts to manage the risks individually and globally.

Vaccines help reduce severe illness and long COVID. But with infections already on the rise overseas and other Omicron sub-variants emerging, we need to be thinking ahead.

This is now the long game, so monitoring our exposure risk, being aware of our symptoms, testing when we suspect we have been exposed, and isolating when we need to, will continue to be the best way to protect ourselves, and those around us.

À lire aussi : Millions of Australians still haven't had their COVID boosters. What message could convince them now?

Catherine Bennett receives funding from the National Health & Medical Research Council, Medical Research Future Fund and VicHealth. Catherine was on the independent expert vaccine advisory group for AstraZeneca Australia, and is a scientific advisory committee member for ResApp and Impact Biotech Healthcare.

Hassan Vally ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.