Each year, the largest contemporary Muslim pilgrimage takes place in Iraq to remember Imam Hussein, the Prophet Muhammad’s grandson. Before the pandemic, this event reportedly drew more than 30 million people, but in recent years participation declined to more than 14 million. This procession from Najaf to Karbala, where Hussein is buried, commemorates the 40th day after his martyrdom, a typical length of mourning in Muslim traditions. In 2022, this falls on Sept. 17.

Following the death of the prophet in A.D. 632, a dispute developed over who would be his rightful successor. This became the source of the Sunni-Shiite divide. For Shiites, Hussein was their third Imam, a beloved spiritual and political leader.

After many years of war, the Umayyad dynasty, which lasted from 661 to 750, established its rule over the Middle East and North Africa. The inhabitants of Kufa, a garrison town in Iraq, were among those who defied the Umayyads and invited Hussein to lead them in revolt. But Hussein and his army were outnumbered and suffered a brutal defeat during the Battle of Karbala. Hussein was killed in 680 on the 10th day of the Islamic month of Muharram, a day known as Ashoura.

Scholars have long been fascinated by the variety of cultural performances evoking intense emotions that occur during Muharram. Since the 1979 Iranian revolution, Shiites have adapted the commemoration to connect Islamic history with the present and to highlight the need for social justice for Muslim populations today.

Public commemorations take place in other parts of the world as well. As a scholar of Shiite communities in Africa, I have studied the processions in northern Tanzania. These are usually scheduled according to the Islamic lunar calendar to fall on the ninth and 10th days of Muharram.

The history of Shiite Islam in East Africa

In Tanzania, Shiite Islam first arrived with the Khoja trading community, a caste from India that converted from Hinduism to Islam. Khojas began to settle in East Africa in the 19th century due to drought, famines and religious persecution in their homeland.

Initially, Shiite Islam was associated with Asian Muslims, whereas African Muslims were predominantly Sunni. Shiite Islam was slow to develop in East Africa.

In 1979, the Iranian government of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran, was overthrown and replaced by an Islamic state headed by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini that rejected Western influence. This cataclysmic event, known as the Iranian revolution, led to a political resurgence for Muslims globally, including in Africa. Muslims of all denominations were inspired by this first successful Islamic revolution since the time of the prophet.

Yet some Sunni Muslims around the world began to inquire about Shiite Islam, the faith’s minority branch, in part because of how they saw Khomeini and his Islamic state depicted in Western media. Some African Sunnis even became Shiites after extensive personal study that compared the primary texts of the various schools of Islamic thought. A 2012 Pew Research Center report put the percentage of Sunnis in Tanzania at 40% of Muslims and Shiites at 20%. Reasons for changing one’s religious affiliation were many. Ultimately, those attracted by Shiite Islam were convinced by its genealogical authority, since it follows the guidance of the family of the prophet. Many perceived Shiite jurisprudence to provide clearer answers to the religious questions they had long been asking.

One Shiite organization in Tanzania, Ahl al-Bayt Centre, or ABC, was established in 1986. With the support of Gulf Shiites, the nongovernmental organization expanded its influence. Now headquartered in a large complex in the environs of Arusha, a city in northern Tanzania, ABC developed into a prominent African-led Shiite network.

Commemorating Muharram in Tanzania

Khojas have been marching in Ashoura processions for the past century in what is today the United Republic of Tanzania. Haji Ali Nathoo was the longtime president of the Khoja Shiite community in Zanzibar, an Indian Ocean archipelago off the coast of Tanzania. He requested from the British colonial government that the 10th day of Muharram, called Ashoura, be a public holiday. This was granted in 1920.

Processions became an annual tradition in Zanzibar and Tanga, a port city in northeast Tanzania. They later gained popularity in urban areas with large mosques, such as Dar es Salaam, Tanzania’s coastal capital and a major commercial center; Arusha; and Moshi, a town near the Kenyan border in the foothills of Mt. Kilimanjaro. Processions require a permit from the government, as roads are closed and police protection is provided.

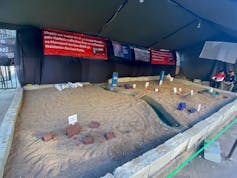

The Khoja Shiite community in Dar es Salaam, the largest in East Africa, constructs a large outdoor display during Muharram. This attracts community members and educates the general public about the Battle of Karbala. In Arusha, a smaller diorama of the battle scene is displayed outside the gates of the Khoja mosque.

Black signs with red, yellow or white lettering decorate mosques and main roads through town. One sign refers to Imam Hussein as “The inspiration for mankind to strive for Justice and Equality.”

Many Shiites attend various “majalis,” or gatherings, and organizations stagger the timing of their events as not to overlap. Food is always provided, ranging from small bags of sugar or rice to biscuits or a cooked meal served in the mosque. This food is thought to bring religious blessings to those who consume it.

Some Tanzanians donate blood, an accepted practice today among Shiites worldwide in remembrance and solidarity with Imam Hussein on the day he died. Blood donations have begun to replace self-flagellation, a blood-letting ritual performed by many Shiite men in order to re-enact and partake in the suffering of the Imam’s family during the Battle of Karbala.

Indian and African Shiite communities usually commemorate religious holidays separately in their respective mosques.

During COVID-19, Khoja mosques conducted religious events online for two years. They are back in person in 2022, while maintaining a hybrid option. The Ahl al-Bayt Centre community continued to gather throughout the pandemic.

Reclaiming the procession for African Tanzanians

I have twice attended the processions in Arusha – during September and October 2017 and more recently again in August 2022. Shiites march through the center of town from the Indian charitable hospital to the Khoja mosque.

Khojas carry staffs called “alam” that signify the battle standards used at Karbala. Decorated with various motifs representing Imam Hussein’s family, these symbolic flags are draped with red-splotched shrouds evoking bloody battle losses. Khoja mosques feature replicas of Middle Eastern mosques where Shiite Imams are buried; these are also paraded in the procession.

Since 2017, Arusha’s African Shiites have been organizing separate processions, which as an anthropologist I also joined. They aimed to reach communities in the outskirts of town and centered their march around African Shiite mosques – not Khoja community landmarks in the city center.

All dressed in black, the color of mourning, marchers carried signs predominantly written in Swahili announcing to the local population the virtues of Imam Hussein. Many men wore T-shirts printed for the procession. Some women and children wore headbands proclaiming “Labaik Ya Hussein” (I am here, O Hussein) or “Proud to be a Husseini.” Led by religious leaders, participants lectured through microphones, rhythmically beat their chests and recited mournfully beautiful Swahili-language “nudba” poetry written by the community about the Battle of Karbala.

As minority Muslims, not all African Shiite communities have the freedom or security to publicly proclaim their beliefs. In West Africa, in Sunni Muslim-majority Senegal, where I have long studied Shiite communities, Muharram is commemorated behind closed doors. In Nigeria, where public processions do take place, state security forces, long at odds with Nigerian Shiites, have attacked and killed participants.

In Tanzania, the government protects freedom of religion. And that is evident in the unique processions of the Indian and African religious communities sharing the peaceful message of Imam Hussein.

Mara Leichtman receives funding from the Luce/ACLS Program in Religion, Journalism & International Affairs and the Center for Islam in the Contemporary World at Shenandoah University.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.