Jeffery Arview didn’t have a backup plan. He joined the military out of high school, went to Iraq, and planned to stay in the armed forces for decades before retiring. Then a seemingly innocuous knee injury set in motion a course of events that would threaten everything he was dreaming of.

“I wanted to retire at 20 years,” he said. “I never really had an exit plan. Never talked about it, never thought about it, not anything.”

One day, he injured his knee playing basketball, and was soon prescribed a powerful regime of opioid treatments, including a fentanyl patch, for the pain, before being medically discharged. It took him a while to realise he was addicted.

The addiction soon consumed everything – his money, his family, his home – and he was homeless for a period before getting clean and finding work at a VA medical center in Tennessee. But there, as a mail clerk, he found himself helping ship out packages containing pharmacy packages, and he was caught stealing pills in a sting operation.

Even with his military service, he had a difficult time finding work afterwards, now that he had a criminal record, a crushing blow after so many already.

“It was really heartbreaking to me, especially after serving in the military,” he told The Independent. “I was really proud. I thought well, ‘When I get out, it shouldn’t be that hard to find a job.’ Once I got that one ding on my background, it became really difficult. At times it made me want to quit, to just stop looking and fall back to the wayside.”

The experience, and in particular the estrangement from his family, inspired him to change things, and a methadone clinic helped him get clean again. Eventually, he found temp work in Tennessee through a staffing firm called Kelly Services, where he has now worked for more than four years and rose to become a full-time talent adviser. Finding a job that would accept him, given his history, proved to be a major turning point in his life.

“It’s a huge difference. You start to build that respect for yourself. Your family starts to respect you again. Your children begin to look up to you again,” he said. “The stability of having gainful employment, having a nice house, having a working car, being able to provide the things for my family like I always wanted to.”

Mr Arview is one of thousands of Americans who have found work with employers who embrace what’s called “second-chance” hiring. It’s a movement rooted in social justice that seeks to view people as more than one mistake in their past and provide job pathways to the 78 million US adults with some kind of criminal history.

Numerous employers ask some kind of question about criminal background during the hiring process, often automatically ruling out candidates with minor or unrelated infractions who would be more than capable of doing the job, according to Jamira Burley, senior fellow at the Responsible Business Initiative for Justice, an advocacy group.

“It’s extreme. One of the first questions you’re asked is whether you have a criminal record. Folks don’t even make it to the interview stage because they’re automatically eliminated based on that question,” she told The Independent.

It’s a barrier she’s seen the impact of in her own life: all 10 of Ms Burley’s brothers, as well as both of her parents, have been incarcerated, and that’s made finding work extremely difficult for them.

“I watched them struggle with getting avenues to employment because of their criminal record,” she added. “What employers miss out on is a wide range of knowledge and skills that we have yet to fully maximize from folks who are formerly incarcerated because of the stigma we have.”

Ready access to good work has also been shown to lower prison recidivism, Ms Burley said.

Conversely, many people end up in the justice system for what are effectively crimes of poverty – lapsed car insurance, unpaid fees, theft for subsistence – impacting their ability to work and creating more desperation.

The barriers to work for formerly incarcerated people are pervasive, according to Ken Oliver, executive director of background check firm Checkr’s social foundation, who was formerly incarcerated himself.

“There are 4,800 legal barriers, laws on the books, that prevent people with criminal records from accessing basic services like employment, housing, other social services,” he told The Independent. “It’s a hold-over, this practice, this culture we built of second-class citizenry, of the king’s England, the notion of civil debt. What happens is, people pay their debt to society, and then there’s like this second life prison sentence that happens. Only you’re free. It’s like a scarlet letter.”

This also harms companies themselves, many of whom are desperately looking for employees during the so-called Great Resignation that has occurred during the pandemic, said Mr Arview, of Kelly Services.

“They lose out on a tremendous amount of talent to fill all of the open roles we currently have across the nation right now if you use this blanket approach,” he said.

Despite these built-in barriers and stigmas, a new generation of companies has sought to leverage its influence to change hiring policies and open the workforce to more formerly incarcerated people.

Background checking and staffing firms like Kelly Services and Checkr argue for a more individualised approach, considering whether a past crime or arrest is directly related to the job at hand, rather than a simple one-size-fits-all bar on justice-impacted people during the hiring process.

Kelly found success with this strategy with a high-profile pilot project at Toyota’s Georgetown, Kentucky, plant, placing more than 600 people with criminal records at the company.

The initiative expanded the automaker’s applicant pipeline for the facility by 20 per cent, decreased attrition by 70 per cent, and increased diversity by 8 per cent, according to Kelly.

“The one thing that we realise, when you think about people who have some kind of a criminal background, we realised early on together that it can be anyone. That can be your brother or relatives or friends or aunt or uncle, et cetera,” said Keilon Ratliff, a vice-president at Kelly. “As we started to dissect that, everyone became more open to the fact, hey just because someone has a criminal charge in their background, it doesn’t mean they’re a bad person and they do deserve a second chance.”

This approach has attracted support from some of the biggest companies in the US, like financial firm JP Morgan Chase, one of the founding members of the Second Chance Business Coalition, which counts firms like AT&T, Walmart, and Visa as partners.

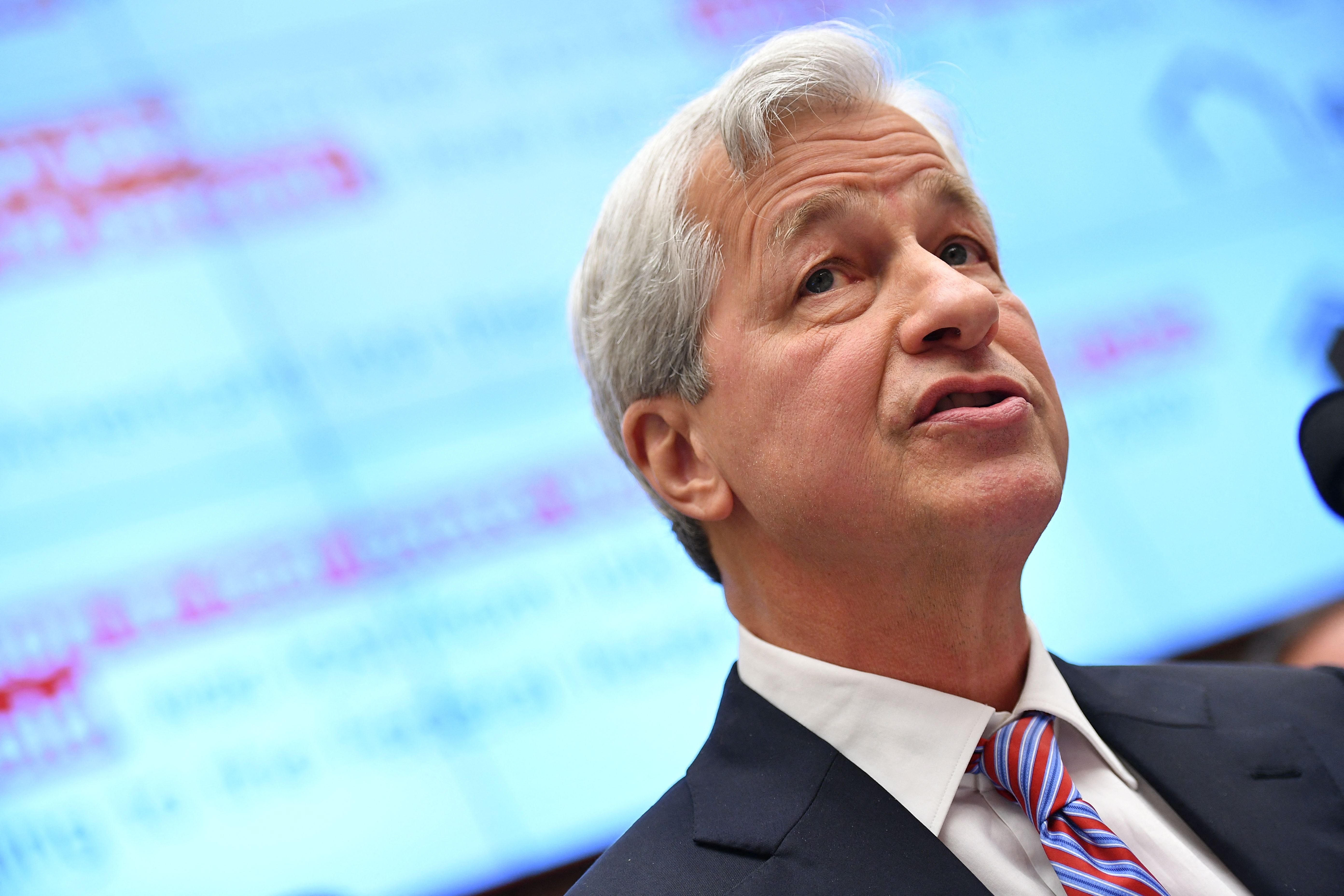

Hiring practices that count out formerly incarcerated people are a “moral outrage” rooted in “systemic racism”, JP Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon argued in The New York Times last year, pointing to the disproportionate number of Black people who are arrested then struggle to get jobs once they’re released.

“Jobs bring dignity and lay a foundation for stability. Employment with a living wage leads to better social outcomes – stronger households, less crime and even better health and well-being,” he wrote in the op-ed, adding, “An inclusive economy – in which there is equal access to opportunity – is a stronger, more resilient economy. That’s something we should all get behind.”

The company is the latest to “ban the box” and only inquires about someone’s criminal background after a conditional employment offer has been made. It also partners with community organisations in Chicago and Columbus, Ohio, to offer job-seekers training and help with the often byzantine process in most states for clearing old convictions off their record – both steps it says are crucial to make hiring more fair.

“Even after someone has completed their justice system obligations, they’re blocked from fully participating in the economy,” Nan Gibson, executive director of JP Morgan’s policy center, told The Independent. “This is huge drag on the earning potential of millions of Americans. These are costs that are not only borne by the individual, but their families, their communities.”

The company’s effort has paid off: In 2020, 10 per cent of new hires at JPMC had a past interaction with the justice system, according to the firm.

It has also sought to use its high profile to lobby for changes to financial industry rules around hiring, as well as push for so-called “clean slate” laws, which use technology to automatically clear qualifying criminal records.

As of late last year, four-fifths of the US population lives in a jurisdiction that has “banned the box” and forbids the use of automatic disqualification because of a criminal background, according to the National Employment Law Project. And advocates have celebrated states like Pennsylvania, Utah, Michigan, New Jersey, Virginia, Connecticut and Delaware for passing bipartisan “clean slate” policies.

But people like Jeffery Arview, the veteran and talent adviser, won’t be satisfied until the societal stigma around those with a criminal charges on their record has lifted.

“Everybody has something they’re not proud of in their life. I promised you,” he said. “These people just want a second chance. You could be that second chance for that person.”

Jamira Burley, Ken Oliver, and Keilon Ratliff will speak at the upcoming American Workforce and Justice Summit 2022 , a two-day gathering of more than 150 business leaders, policy experts and campaign organizations focused on how corporations can meaningfully engage in justice issues and create change in the workplace and beyond. AWJ 2022, a project of the Responsible Business Initiative for Justice, will take place in Atlanta, Georgia, on 4 and 5 May. The Independent will be reporting from AWJ 2022 as media partner.