The multiverse started not with a bang, but with a flash. Two, actually.

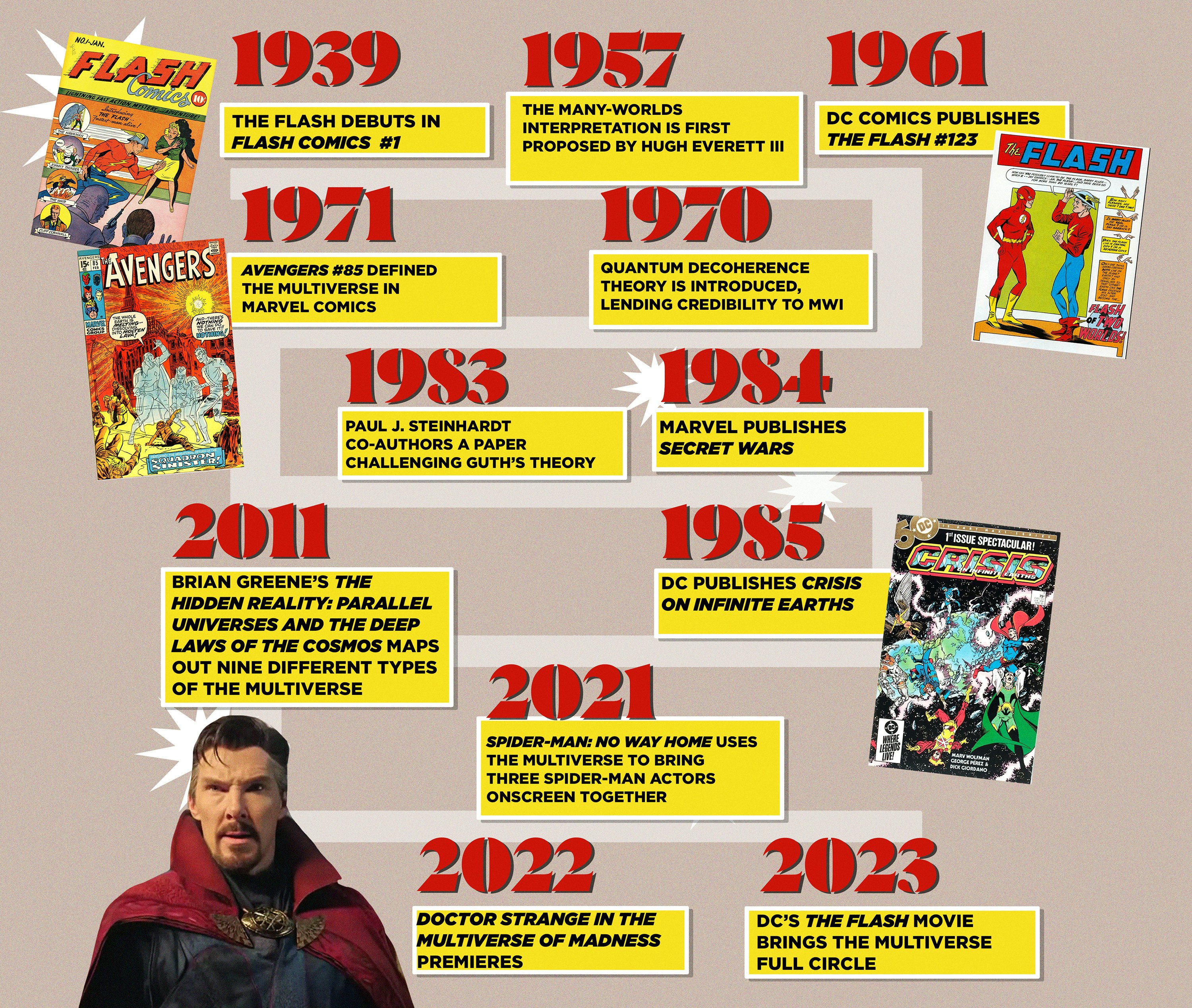

In 1961, DC Comics published the 123rd issue of The Flash. In its pages was the story “Flash of Two Worlds,” where creator and writer Gardner Fox staged the historic meeting of two superheroes from parallel worlds.

Protagonist Barry Allen sits in the living room of retired crime-fighter Jay Garrick, the first man in comics to go by The Flash. “My theory is,” Barry says in exposition (and awkwardly dressed in his spandex costume), “both Earths were created at the same time in two quite similar universes! Destiny must have decreed there’d be a Flash on each Earth!”

While new at the time, both in science and sci-fi, multiverse stories have since become nearly as popular as time travel.

The word “multiverse” isn’t printed in the comic, but The Flash #123 was the beginning of the multiverse in superhero pop culture. Sixty-one years later, the multiverse is enjoying a rare moment of prominence as the defining sci-fi premise of the pandemic era. It’s in TV shows like Stranger Things, Rick and Morty, and Loki, and in theatrical billion-dollar grosses like Spider-Man: No Way Home. Indie darling Everything Everywhere All at Once, from directors Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert, proves the multiverse isn’t just for blockbuster audiences but arthouse enthusiasts, too.

“The multiverse is so exciting because we live in a unique moment where there’s too much information,” Kwan tells Inverse. In the hit multiverse dramedy, actress Michelle Yeoh stars as a laundromat owner who harnesses her powers from other realities. “There’s too many stories, too many worlds colliding every day in our heads. The multiverse is a perfect metaphor for what it feels like to be alive today.”

“Things are fragmented... Things are not as solid as they used to be.”

“Things are fragmented,” observes Peter Ramsey, co-director of Marvel’s first multiverse film, Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse. “The idea that there’s more than one set of possibilities is something that speaks to people in a very real way. It’s impossible anymore to agree on what’s true. Things are not as solid as they used to be.”

Michael Narducci, a writer on the TV show Superman & Lois that also explores the DC multiverse, says the concept is no longer too complex for today’s genre-savvy audiences.

“Gone are the days when anyone can say, ‘That’s a cool idea, but the audience just isn’t going to get it,” Narducci says. “The audience gets it. The audience is craving it and loving it.”

Even more multiverse movies are on the way. Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness plunges the Marvel Cinematic Universe into the multiverse on May 4. Into the Spider-Verse is getting two sequels, beginning in June 2023. That same month, DC’s The Flash movie will deliver a multiverse-centric plot, the journey of the multiverse will come full circle.

But in the fields of astrophysics and cosmology, the multiverse is understood differently. In 2011, string theorist Brian Greene outlined a total of nine different types of the multiverse in his book The Hidden Reality: Parallel Universes and the Deep Laws of the Cosmos. (One of them, the quantum multiverse, passively resembles the one often seen in movies — more on that later.)

While scientists interviewed by Inverse are quick to point out that no version of the multiverse is proven, it has nevertheless sparked debates among brilliant minds for decades. Amid so many multiverse-centric movies, these scientists say the concept’s sudden popularity has only complicated the future of their study.

“There are many things called the multiverse. It’s a very loose concept,” Clifford Johnson, a professor of physics at the University of Southern California, tells Inverse.

The multiverse is a “proposed solution to a number of interesting problems,” Johnson says. “Because there’s so much multiverse in entertainment, people think it’s a thing scientists believe in. It’s not. It’s fun. We all like to play with ideas. But there is no smoking gun for the multiverse.”

The multiverse may not be real — at least, not definitively — but its popularity is undisputed. Perhaps knowing where and how the multiverse began can reveal where it’s going next.

“Many worlds”

The version of the multiverse audiences understand doesn’t originate in the study of space and time. It begins in quantum mechanics.

In 1957, physicist Hugh Everett III risked his reputation when he first proposed the many-worlds interpretation, or MWI. In a nutshell, MWI theorizes that all possible results of a quantum experiment or action are realized in another world, branching off from that point.

In quantum physics, the state of the tiniest particles has several possibilities until you look at them. In the many-worlds interpretation, once you look, a new “World” is created where the particle is in the opposite state of the one observed by scientists in our world. It adds up to an almost infinite number of realities since quantum particles are the building blocks of all matter around us. (Community episode “Remedial Chaos Theory” is a humorous demonstration of MWI. It also birthed the multiverse meme the “darkest timeline.”)

MWI was such an unpopular idea that Everett was ostracized in his field. His ideas were ignored until later in his life, when, in the 1970s, the discovery of quantum decoherence — basically the understanding that quantum particles are continuously thrown out of state (and thus, coherence) by the environment around them in experiments — lent MWI and Everett greater credibility. Even today MWI is still in dispute, but neither MWI nor Everett has vanished from memory.

While scientists ignored Everett, comic books embraced his ideas — by accident. Shortly after the publication of MWI, DC Comics unwittingly depicted it in The Flash #123.

When DC published Flash #123, comics were in full swing of the “Silver Age.” Named for both the creative zeitgeist and renewed sales of superhero comics (after a brief decline following World War II), the Silver Age saw an influx of science fiction stories in comics. The trend coincided with America’s participation in the space race, which fostered widespread interest in sci-fi and its ideas of the future.

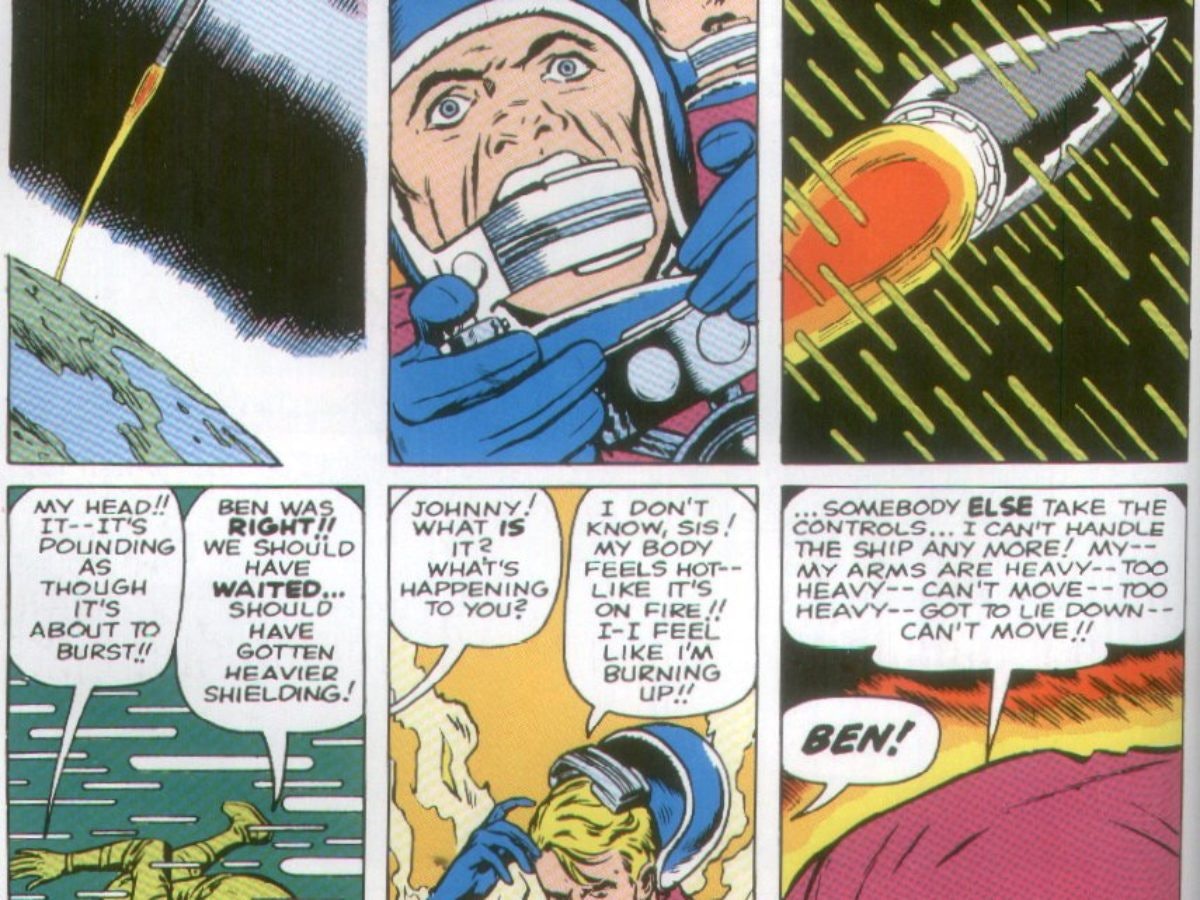

Comics went all in. Characters of the Golden Age, like DC’s Green Lantern, pivoted from fantasy and magic to alien planets and cosmic origins. After rebranding from Atlas Comics to Marvel, the company debuted Fantastic Four, Spider-Man, and the Hulk, funky new superheroes rooted in experiments gone awry.

The Flash, too, got a sci-fi makeover. After Jay Garrick’s time as The Flash came to an end in 1951, the character was rebooted in the 1956’s Showcase #4. On its cover was Barry Allen as the newer, modern Flash, donning a sleeker red and yellow costume befitting the space age.

While Barry fought crime as the “new” Flash, longtime fans were left to wonder about the whereabouts of the “old” Flash. Soon enough, DC found a roundabout way of placing Jay and Barry in the same room: the multiverse.

“The multiverse is the idea that different parallel universes exist, featuring different iterations of familiar characters,” says Reed Tucker, author of the book Slugfest: Inside the Epic, 50-Year Battle Between Marvel and DC.

Tucker tells Inverse there was initially no grand plan for comics to expand mythology. At the time, DC’s only concern was the bottom line. Working in comics at the time was like working in a factory, not a laboratory. Uniting the two Flashes of two eras wasn’t a symbolic celebration of the superhero genre’s maturity. Nor did it come from any cited interest in Everett and his crackpot theories. Instead, the multiverse came out of a petty bet in the DC offices.

“The cover came first”

During the Silver Age, covers sold comics. “Oftentimes, the cover came first,” Tucker says. “A kid would come to a spinner rack and choose the one that promised the most exciting story.”

DC was particularly keen on covers. The company’s head publisher at the time, Irwin Donenfeld, kept a log of cover sales month to month. “He would try to extrapolate patterns out of that so he could push more stuff onto the stands,” Tucker says.

Artist Carmine Infantino (who co-created Barry Allen as the new Flash) typically drew covers first. The actual story was figured out later. During production of The Flash #123, Infantino “was having a competition” with editor Julius Schwartz to see if he could draw a cover Schwartz “could not write a story” from.

In 2007, Infantino recalled:

“I’d do a cover, and dammit, they’d write the story around it, so I was getting very upset by this … I did a cover with some guy in the foreground and two Flashes running up, he’s saying, ‘Help!’ and they’re both saying, ‘I’m coming!’ So I put it on [Schwarz’s] desk and I said, ‘Here. Solve this!’ and I walked out. By the time I got home my phone rang. He said, ‘We got it solved. I went through hell.’ I couldn’t believe it.”

After The Flash #123, DC canonized characters of the “Golden Age” as inhabitants of a parallel Earth, dubbed “Earth-Two.” When a story featuring both the Justice League (of Earth-One) and Justice Society (Earth-Two) took off with fans, exploring the multiverse practically became an annual tradition.

Ten years after DC began mapping out its multiverse, so too did rival publisher Marvel.

“Probably the first inking of a multiverse came in Avengers #85,” Marvel editor Tom Brevoort tells Inverse. Published in 1971 (a decade after “Flash of Two Worlds,” and a year after quantum decoherence helped validate Everett’s many-worlds interpretation), Avengers #85 introduced the Squadron Supreme, a pastiche of DC’s biggest characters from an alternate reality.

“While there had been other dimensions in Marvel stories for years, this was the first time we saw a defined parallel Earth with its own characteristics,” Brevoort says.

Six years after Avengers #85 came What If, an anthology comic that explores alternate takes on Marvel characters and storylines (“What if Spider-Man joined the Fantastic Four?” “What if Iron Man was a traitor?”). Both Avengers #85 and What If emerged from the mind of editor Roy Thomas, who grew up a fan of DC’s Golden Age heroes and relished their return via the multiverse. “He brought that concept to Marvel and gave it a more rationalist spin,” Brevoort says. “[What If] concretely established multiversal construction [for Marvel].” Today, the comic lives on in the animated series What If…? on Disney+.

Marvel and DC spent the 1970s toying with the multiverse. It just so happens that by the end of that same decade, scientists were grilling themselves about what the multiverse might actually involve. In 1979, physicist and cosmologist Alan Guth, currently a professor at MIT, developed his theory of cosmic inflation, which was crafted to solve an overwhelming mystery: how the universe grew in the aftermath of the Big Bang.

“Guth suggested that, unlike the usual story [of the Big Bang] where the universe just starts, there was an entirely different kind of energy that could pervade the universe,” Sean Carroll, a professor of physics at the California Institute of Technology, tells Inverse. “What Guth suggested was a kind of energy, what you and I would call dark energy. If you have super dense, exotic dark energy, it can inflate the universe. The weirdness of this energy is that, rather than slowing the universe due to gravity, it speeds up expansion.”

The multiverse, Carroll says, was a byproduct of Guth’s theories of inflation. In growing the universe, there are bubbled regions where the laws of physics behave differently from another. This is, technically speaking, the “real” multiverse, and it’s very different from the version seen in superhero comics and movies.

“That theory is a myth.”

“The textbook [definition of the] multiverse is the inflationary multiverse,” explains Brian Cox, a professor of physics at the University of Manchester. Cox says the multiverse is the realization of “bubble universes” where the laws of nature differ. It’s helpful to think of the multiverse like a quilt blanket; patterns and designs inhabit their own squares but are unified by the same structure.

“Picture some kind of almost fractal-like infinite collection of bubble universes,” Cox says. “That is called the inflationary multiverse.”

Sean Carroll, who served as a technical consultant on Marvel movies like Thor and Avengers: Endgame (the latter film’s jab at Back to the Future “was my fault,” he jokes), has an even simpler explanation.

“That’s really just the idea that in different parts of space, the laws of physics can be very, very different,” Carroll says. “Certain features like particles and strengths of masses, maybe those are different somewhere else.”

Inflation emerged as a theory to explain certain properties of the universe, including one problem in particular: its flatness. While the Big Bang should have left the universe patchy and irregular, it instead left behind a smooth distribution of matter and energy. But, as some physicists like Paul J. Steinhardt of Princeton University found out, the actual math of inflation calculates a patchy universe anyway.

“That theory is a myth,” Steinhardt tells Inverse.

In 1983, Steinhardt first challenged Guth’s theories when he co-authored a paper arguing that inflation doesn’t produce a uniform universe. Shortly after, Russian physicist Andrei Linde wrote another paper that Steinhardt says “introduced the term multiverse into the lexicon.” (Meanwhile, comic publishers rolled onward, with Marvel’s Secret Wars and DC’s Crisis on Infinite Earths telling seminal multiverse stories in 1984 and ’85, respectively.)

Steinhardt doesn’t formally identify as a skeptic of the multiverse, but if a multiverse is the result of a theory, he considers it “a fatal flaw.” “It does not help explain our universe. Quite the opposite,” he says.

He adds, “If I tell you a theory that allows every possibility, there’s no test that you can perform. That puts this theory outside the bounds of normal science. It becomes a matter of faith.”

“There is no smoking gun for the multiverse.”

Inflation and the multiverse have their famous endorsers, including the late Stephen Hawking, whose final paper before his death speculated humanity’s existence in a quantum multiverse.

Still, it’s just a theory.

“There is zero evidence at present for anything that points to a multiverse,” University of Southern California physics professor Clifford Johnson tells Inverse.

“There’s nothing wrong with [the many-worlds] interpretation,” he adds, “but right now, it has no observational consequences. It’s fun words, but it’s not a very economical solution. You’re inventing billions of universes every fraction of a second just to solve this one thing.”

Infinite Earths

In the years since Steinhardt and Guth kicked off one of the most prolific beefs in the scientific community, comic books continued experimenting with the multiverse’s plasticity. In 1985, DC’s ambitious crossover series Crisis on Infinite Earths, a 12-issue serial by Marv Wolfman and George Perez, saw the collision and dissolution of DC’s multiverse status quo. Characters fought against (and teamed up with) their doubles from other worlds in a battle for survival against a cosmic entity called the Anti-Monitor.

True to how DC began the multiverse, with eye-catching covers designed to sell comics, Crisis on Infinite Earths ended the multiverse to appeal to a broader readership. After lagging behind Marvel in sales for years and burdened with an incomprehensible continuity, Crisis allowed DC to start over with a clean slate with a streamlined universe. Crisis also saw the death of Barry Allen as The Flash, which symbolically and literally laid the Silver Age to rest.

Crisis on Infinite Earths ended DC’s multiverse for a short time, but it began a legacy that is still felt today. The comic was adapted in a 2019-2020 television crossover event for the shared universe of DC TV shows known as the “Arrowverse.” The special notably built a bridge connecting the worlds of TV to movies, and did so with — you guessed it — a meeting of two Flashes: The Flash series actor Grant Gustin and Justice League film star Ezra Miller.

“The multiverse… is a storytelling tool.”

Marvel is also exploring its multiverse in serious ways. Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness, starring Benedict Cumberbatch, is primed to be the first big movie of the summer season.

From the complex web that is corporate studio acquisitions, the buzz around Multiverse of Madness is its rumored cameos of X-Men characters who have been, until now, legally unable to appear in a Marvel Studios-produced film. Mirroring the unwieldiness of cosmic inflation and its differing physics, the multiverse is becoming a solution to finally consolidate Marvel’s onscreen stories.

“The multiverse… is a storytelling tool, one that allows for different and specific types of stories that further widen the possibilities,” Marvel’s Brevoort says. “It’s a big part of our storytelling for several decades now and very much entwined in the DNA of the operation.”

Multiverse of madness

With the explosion of multiverse adventures on screens, scientists are divided on what that popularity means. Just like the multiverse itself, some are skeptical while others have faith.

“It’s not a problem,” Brian Cox says. “I’m in favor of Hollywood movies taking as much science as they want. Even if they get it wrong, it means we can talk about how they got it wrong.”

“I have no problem with the artistic use of it,” adds Steinhardt, though he has caveats.

“You’re allowed to imagine anything you want. On the other hand, by using a term, which has a technical definition, you have to realize you’re introducing ideas, especially into young people’s heads, that they’re going to have trouble distinguishing later on.”

“What I would like them to do is to get the spirit of science right.”

One of the first lessons Steinhardt teaches his students every semester debunks the idea that the Big Bang was a literal explosion. With one version of the multiverse influencing movies, Steinhardt is concerned audiences get the wrong impression. “I find it’s very hard to unteach something,” he says. “It’s better to teach it right the first time and not have to unteach it.”

“I like to think there’ll be a positive effect,” Sean Carroll says. “I don’t think it is the job of a giant tentpole to give science lectures. They’re not there to educate or even to get the science right. What I would like them to do is to get the spirit of science right.”

On whether movies should be more specific on the version of the multiverse they illustrate, Carroll is even less strict. “Who cares? I’m not going to demand people use the right terms. What I would like is if they understood the different [ways] a multiverse could exist,” he says.

Even scientists concede the multiverse is an appealing pathway for emotionally-driven stories.

“We all love to think counterfactually. We all love to think, ‘What if things had gone differently?’” says Carroll. “It’s a great storytelling device to sort of take those counterfactual possibilities and make them real.”

“I fully endorse storytellers [who] want to include some of the fun ideas that we get to play with as professionals,” Clifford Johnson says. “I don’t think science belongs to us. It doesn’t belong to scientists. We are privileged to discover and explore. I think we have a responsibility to tell people what we’ve been up to and get them to play with it as well.”