From the opening days of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, one of Moscow’s earliest strategic aims quickly became apparent as its armoured columns advanced along the coast in an effort to seize Ukraine’s coastline and cut it off from the sea. The seizure of Ukraine’s ports would strangle the country economically at a time when Ukraine most needs the funds to fend off Russia.

Several months in and Russia has been partially successful. Two of Ukraine’s five main commercial ports have been taken – Berdyansk and, after a brutal siege, what remains of the port of Mariupol. Both are in the northeast of the Black Sea.

Commercial shipping that sails from the Black Sea is well placed, having immediate access both to the countries bordering the Mediterranean and to the Suez Canal and the markets beyond.

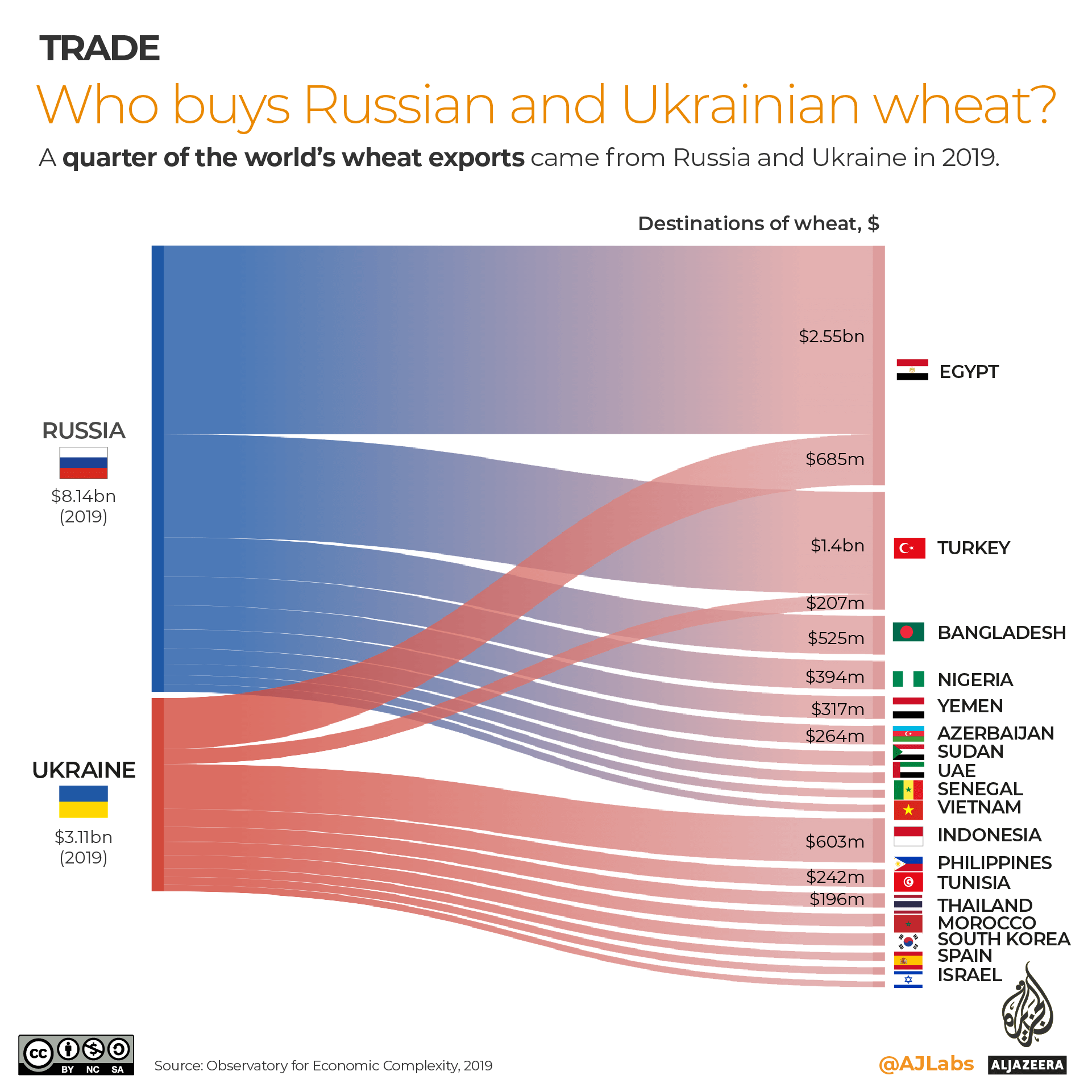

Ukraine accounts for 9 percent of the world’s wheat, 15 percent of its maize and 44 percent of global sunflower oil exports. A quarter of Bangladesh, Egypt, Indonesia and Pakistan’s wheat comes from Ukraine.

The country’s main port, Odesa, is still in Ukrainian hands, as is Mykolaiv. Between the two of them, they accounted for 80 percent of Ukraine’s pre-war grain exports. Russia’s attempts to take these important trade hubs and the surrounding territory have failed and its advance has stalled. Russian units now face mounting resistance as Ukrainian units have launched a sharp counterattack on Russian forces in and around Kherson and Mykolaiv, as they struggle to retain control of this vital southern coastal sector.

Odesa, Mykolaiv and Chernomorsk still function as ports but Russia has initiated a blockade in order to ensure no grain leaves the country. Commercial shipping has been warned off, sea mines have been deployed in the waters leading to the port and the whole area of the Black Sea is constantly patrolled by Russian warships and fighter aircraft.

Snake Island

The key to this blockade has been Snake Island. A tiny islet 48km (30 miles) off the coast of Ukraine and Romania, it was taken by Russia in the opening days of the war. Strategically placed, it controls the approach waters to Ukraine’s last three remaining commercial ports and is being heavily armed by Russia.

Ukraine’s navy is almost non-existent and at the start of the conflict Russian warships operated with near impunity. That all changed when the Russian heavy missile cruiser Moskva was sunk on April 14. The powerful warship – the pride of the Russian navy – was hit and sunk by two Neptune anti-ship cruise missiles some 96km (60 miles) from Odesa. The Neptune is locally made and based on an earlier Russian design. With a range of 280km (174 miles), it is designed to drop to between 3 metres and 10 metres (10-33 feet) above the surface as it approaches its target, making it hard to detect. Its 145kg (320 pounds) warhead is designed to sink vessels of up to 5,000 tonnes, but two strikes on the Moskva did so much damage that it eventually sank, much to the alarm of the Russian navy, which pulled back its warships from the Ukrainian coast. Snake Island has since then taken on greater importance and has been heavily fortified with advanced weapons.

Considered an “unsinkable destroyer” by some analysts, the island is bristling with search radar, at least five Tor and two Pantsir anti-aircraft systems and fuel and ammunition dumps. Protected by trenches and revetments, it is now a far tougher target for Ukraine’s military to destroy.

Several attacks by Ukrainian armed TB2 drones have done damage but many of these valuable weapons have also been shot down in the process. Heavily armed, the Russian forces on the islet are increasingly able to repel attacks.

The expected arrival of offensive systems like long-range artillery and S-400 air defence units would allow Russia to dominate the airspace over the south of Ukraine in addition to the northwestern section of the Black Sea. The addition of artillery would allow the island to act as a firebase from which targets on land could be attacked and destroyed.

Ukraine’s military, supremely aware of Snake Island’s strategic position, has kept up the attacks which have helped degrade Russia’s military presence there. A helicopter supplying troops has been shot down, at least one radar site has been damaged and a supply boat delivering troops, food and an air defence system to the garrison was hit and sunk by a newly-supplied Western Harpoon missile, in an effort to drive Russian forces from the island.

Russia still has control of Snake Island and its position and heavy defences are a thorn in Ukraine’s side. The battle between the two sides has intensified as Ukraine tries to take back control of the islet, striking out at other targets in order to draw Russian forces away.

Changes in naval tactics

On June 20, a Russian offshore oil platform was badly damaged by air raids – by American-made rocket artillery, according to the Russians. Situated off the coast of Crimea, the platform is the latest target to be considered by Ukraine as it seeks to increase the number of targets it strikes, hoping to spread Russia’s forces and defences over a wide area, thinning them out and exhausting Russia’s large reserves of military equipment. The Kerch Bridge joining the Crimean Peninsula with the mainland is now said to be a target, requiring Russia’s military to expend even more resources defending it.

While attacks pick up the pace, more subtle weapons have been brought into use by Russia as it attempts to ensure civilian shipping is not tempted to brave it out and use the commercial ports still under Ukrainian control. Sea mines have been laid at the entrance to these ports, most notably in Odesa.

While these ships may have been tempted to call Russia’s bluff on whether they would be fired on by manned weapons systems, mines are automated and will explode regardless of the nationality of the vessel that collides with them.

One of the dangers of floating mines is they will eventually drift. Warnings have been issued to maritime traffic in the Black Sea and mines have been spotted as far south as the Bosphorus. The Turkish military has defused them and urged, along with a host of other countries, that a solution be quickly found. Turkey controls much of the Black Sea, which it considers a vital interest to the country. It also controls – and is the custodian of – the sole waterway that leads from the Mediterranean to the Black Sea, making Turkey a strategic player in the region.

A Turkish military delegation is due to visit Moscow to negotiate safe passage of commercial shipping to Ukraine’s commercial ports, in an effort to kick-start stalled grain exports that are vital for food production in countries around the world. There are fears a growing food crisis – made worse by global climate patterns affecting harvests and a general global supply-chain slowdown – could start to have serious consequences for regional stability if these vital commodities do not begin flowing in serious quantities. Meanwhile, Russian missiles continue to hit Ukraine’s economic infrastructure and grain silos in Mykolaiv have been badly damaged, further hampering Ukraine’s ability to supply the large amounts needed.

The naval war in Ukraine, the mining of its ports and the attacks on strategic targets are Russia’s attempt to strangle Ukraine economically, denying it the raw materials and funds needed to fight an industrial war. In 2020, Ukraine’s exports amounted to $52.7bn and it badly needs the money as the prospect of a longer war now seems more likely.

Vital crops in Ukraine are due to be harvested in a few weeks which has added to its sense of urgency. Despite alternative routes being considered for its exports, such as a route to Baltic ports, most are overland and just do not have the capacity to export these commodities in the amounts needed. A single container ship is equal to 50 trainloads of grain and with at least 80 percent of all global trade travelling by sea, control of these Black Sea ports is vital.

Russia’s grip on Ukraine’s vital trade arteries shows no sign of easing up, despite international pressure. The effect of the blockade is not just being felt in Ukraine but around the world as both demand for, and prices of, basic foodstuffs continue to rise. With Ukraine’s harvest season almost here, most of its able-bodied population caught up in the fighting and the continued attacks on the country’s agricultural infrastructure, the likelihood that Ukraine can export the amounts it needs to sustain its war with Russia is starting to fade, which is exactly what Russia is hoping for.