Rohingya activists, advocates and health organisations in Australia have been frustrated by the lack of support provided to displaced Rohingya people.

This ethnic minority group called Myanmar home for centuries before being made stateless by the government in 1982, persecuted due to both their race and majority Muslim religion.

While a few hundred Rohingya refugees have resettled in Australia since 2008, at least a million continue to live in desperate circumstances in the world’s largest refugee camp: Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. There are many horrifying stories of displaced Rohingya facing physical and sexual violence and dire health conditions.

In August, the Refugee Council of Australia council called on the government to remain steadfast on its 2023 pledge to increase resettlement places and provide aid to those still living in camps, but we’ve yet to see substantive action.

As such, local advocates are turning to more creative ways to raise awareness, such as hosting events focused on Rohingya art, culture and resistance. These projects help strengthen local Rohingya communities, while educating the public.

Read more: 7 years after genocide, plight of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh is exacerbated by camp violence

For my research, I’ve investigated how activist groups use creativity and pleasure to encourage broader participation in their efforts.

This work led me to local Rohingya community members and their allies at the Creative Advocacy Partnership, (cofounded by four Australians with Rohingya community leaders). They told me traditional advocacy could increase feelings of oppression and “othering”.

Through interviews with them, I found creative advocacy projects can serve several empowering purposes, including preserving culture (and elevating culture over suffering), honouring ancestors and balancing power dynamics between aid workers and displaced people.

Building bridges to Cox’s Bazar

Last year, Creative Advocacy Partnership cofounders Tasman Munro and Arunn Jegan (who is also a Médecins Sans Frontières emergency coordinator) travelled to Cox’s Bazar to create artworks in collaboration with Rohingya artists, children and storytellers. One outcome was a sculpted bamboo story panel based on a Rohingya folktale.

Munro described the experience to me:

we sat with [Rohingya creators] Nuru Salam and Nurus Safar, in the front room of their shelter and talked about the project. We saw each other’s work, discussed the tools we needed, the time we had and how flexible the bamboo was […] already, there was a common language and understanding. Over two weeks we had the chance to make together, to learn the artful process of stripping bamboo, figuring out the cane-glass technique, listening to Rohingya folktales and collaborating with talented kids to design and make the story panel.

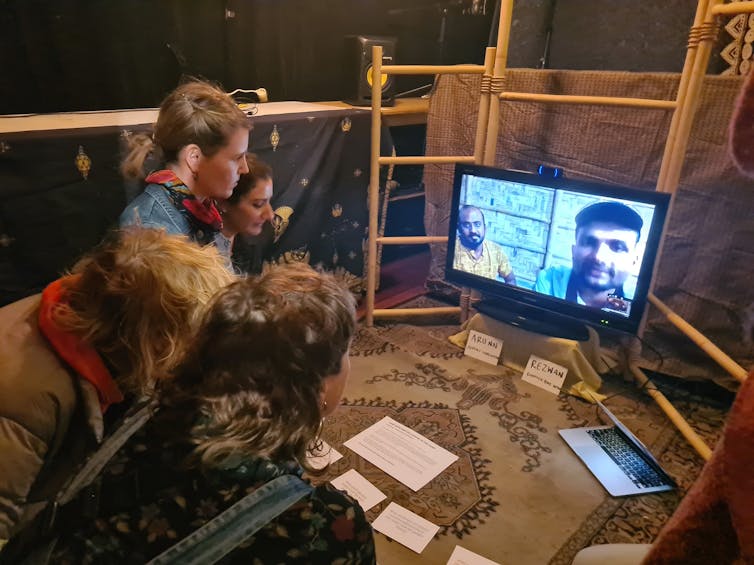

This project was shared back on Gadigal land in an exhibition curated by the Creative Advocacy Partnership, Médecins Sans Frontières and Rohingya youth leader Asma Nayim Ullah. It provided ways to engage with both the refugee crisis and Rohingya culture through a photo exhibition, film screening, and live video call set up with Jegan, who was still stationed in Cox’s Bazar, and a Rohingya storyteller named Rezwan.

A delicious meal was cooked by the Australian Rohingya Women’s Development Organisation. The deep connection between both places was palpable.

Jegan has lived the difference between traditional advocacy methods (such as focus groups or clinical rounds in refugee camps) and arts-focused projects. He is passionate about shifting the power dynamics of aid so that local voices are heard and disadvantage isn’t perpetuated.

He said that, outside of these creative approaches, he’d noticed dynamics that held aid workers in higher regard than the disenfranchised communities they served:

The arts has been ‘the great leveller’ for me. It places the community as experts, where their skills and crafts are centred, and their stories, plight, and are story-told through them, rather than through simply their misery, disease, or their service user-ship (usage). I’ve found that by using arts, I’ve created a stronger, more equal relationship.

Creative advocacy can change discourse

Here on Gadigal land, prominent Rohingya activist and cofounder/director of the Rohingya Maìyafuìnor Collaborative Network, Noor Azizah, told me millions of Rohingya continue to face extreme hardship:

With 2.8 million Rohingya worldwide, only 1% live in freedom while 99% remain in refugee camps, in hiding, in exile, or trapped in Arakan, Burma. Cox’s Bazar alone hosts nearly one million Rohingya refugees and the situation there remains dire. We need to ensure their voices are heard as this protracted crisis prevents Rohingya from thriving.

In August, to mark the seventh anniversary of the Rohingyas’ 2017 mass displacement from Myanmar, Azizah co-hosted an event called the Rohingya Social. She described it as an

opportunity to amplify voices and remind everyone that the fight for dignity, rights, and justice continues for those who remain displaced.

The public were invited to share in celebrating Rohingya cuisine, culture and survival over an authentic three-course meal. The event featured stories from survivors and Médecins Sans Frontières workers, poetry by a local Year 11 student and colourful paper decorations created by displaced Rohingya children in Malaysia.

The night was full of generosity of spirit. As Azizah wrote on her social media:

Cooking Rohingya food for family and friends is more than just preparing a meal. It’s about honouring our ancestors who passed down these recipes, supporting our people currently facing struggles, and preserving our culture despite the challenges we face.

The author does not work for, consult, own shares in, or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article. Relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment are with the following climate justice and worker's rights organisations: Community Environmental Monitoring (co-founder), Workers for Climate Action (member), National Tertiary Educators Union (member), National Association for Visual Arts (member).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.