It’s been just over 40 years years since the CDC reported knowledge of a new, mysterious illness that killed five gay men in Los Angeles in 1981. In July of the same year, the New York Times published its first article on the virus: “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals.” The attitude of the time was that HIV/AIDS was a “gay cancer,” only affecting queer people and drug users.

By the time then-president Ronald Reagan addressed the virus in 1985 — a whole four years after the CDC’s announcement — it was clear that HIV/AIDS was a crisis many felt apathetic toward. Some even felt that marginalized communities deserved it.

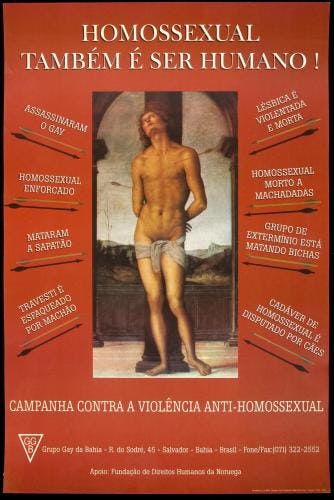

For activists, HIV/AIDS was an emergency, a time of “any means necessary,” says Jessica Lacher-Feldman, co-editor of Up Against the Wall: Art, Activism, and the AIDS Poster. Her new book explores the AIDS poster as an essential intersection of art, education, and direct action spanning decades and generations. Up Against the Wall pulls from one of the largest archives of its kind: Over 8,000 posters make up the collection, featuring decades of work, 76 languages, more than 130 countries, and every state in the U.S. The AIDS poster collection, which was donated to the University of Rochester by physician and medical historian Dr. Edward C. Atwater, is a reflection not just of the past, but also of our ongoing relationship to sex, queerness, and HIV/AIDS.

But what makes a poster worthy of a whole book, an entire archive, and a corresponding exhibit?

“Dr. Atwater saw the need to document the AIDS crisis as a shift in our culture and collective conscience,” says Lacher-Feldman. “He saw the HIV/AIDS poster as examples of social history and felt compelled to document the AIDS crisis through the lens of how we were educating each other in order to stay alive.”

In this way, posters are confrontation. They both create and respond to culture. They have the ability to invade both public and private spaces — think a street corner, a gay bar bathroom, a church door, an STI testing clinic wall, a community center — which matters when your society at large, especially the government, would rather joke a crisis away than help. AIDS activists used these posters as a form of direct action — public displays of protest and knowledge that forced people to look by any means necessary.

“The posters [were] meant to meet people where they were, both physically and psychologically, in order to make a difference. Some of the posters are very funny, tongue in cheek,” says Lacher-Feldman. “Some are truly scientific, and others are creative, obtuse, shockingly straightforward, subtle, or powerful … It is a matter of knowing your audience.”

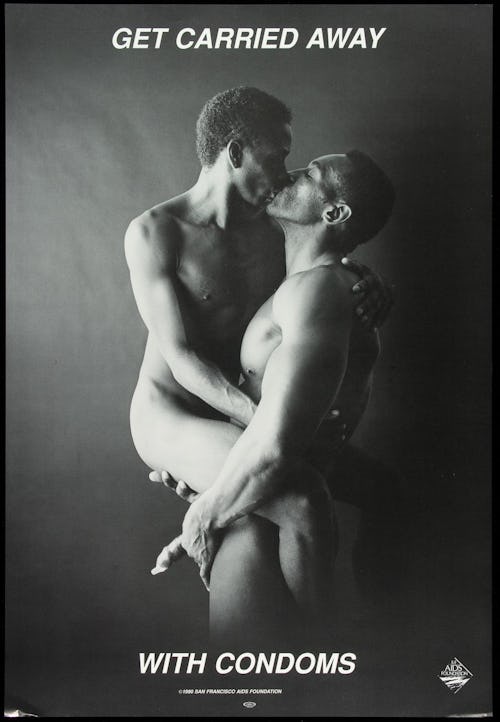

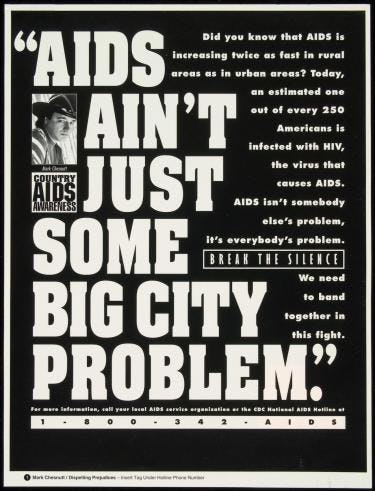

Taken together, the posters were targeted, guerrilla-style activism made on a mass scale for as many audiences as possible. Some are directed toward the gay community, trans folks, lesbians, men who sleep with men, or drug users.

Others were aimed at institutional apathy or willful harm. The 1988 poster that reads, “The Government Has Blood on Its Hands. One AIDS Death Every Half Hour,” features a single, bloody handprint and bold, unmistakable text. A passerby may have been able to avoid news articles, health clinics, or any personal stake in AIDS — but it would be hard to unsee that handprint.

Other posters aimed at religious institutions — often the Catholic Church, which in 1988 was embroiled in conflict over the use of condoms — served as an act against church doctrine and a method to prevent the spread of HIV. Some posters looked toward the communities most affected by HIV/AIDS and sought to educate viewers on safe sex, clean needle use, and how HIV/AIDS spreads and affects the body.

But perhaps most importantly, the AIDS posters interacted not only with their audiences, but also with a culture of homophobia. In the ‘80s especially, talking about sex and gayness wasn’t just extremely taboo; it was dangerous. In 1986, The New York Times reported rising hate crimes against queer people, “as homosexuals have become more vocal in their pursuit of civil rights and more visible because of publicity surrounding the spread of AIDS.” But this was a time of crisis, and the AIDS activists were forcing the culture to shift.

“Before the HIV/AIDS crisis, no one saw the word ‘condom’ in print, in a newspaper, or talked about so openly,” says Lacher-Feldman. “The posters not only responded to the wider political and social context surrounding AIDS, they created wider political and social context by bringing awareness and action. The posters are important now and will be forever in that they serve as a model for creating direct action and awareness.”

Now, 41 years after the start of the HIV/AIDS crisis, we are again faced with a pandemic. The AIDS crisis, much like COVID, still isn’t over. But especially now, as we are again reminded of the emotional, physical, societal, and economic costs of a pandemic, we all have a responsibility to pay attention to what elder activists offered and accomplished — even with their backs up against the wall.