People with disabilities arguably stand to gain the most from good public transport, but are continually excluded by transport systems that still aren’t adapted to their needs as the law requires. One in six people aged 15 and over with disability have difficulty using some or all forms of public transport. One in seven are not able to use public transport at all.

Under the Disability Discrimination Act 1992, Australia’s public transport systems were expected to be fully compliant with the 2002 Transport Standards by December 31 2022. Not only have many of our bus, train and tram systems failed to meet these targets, but the standards themselves are outdated. The standards are under review and public consultation has begun.

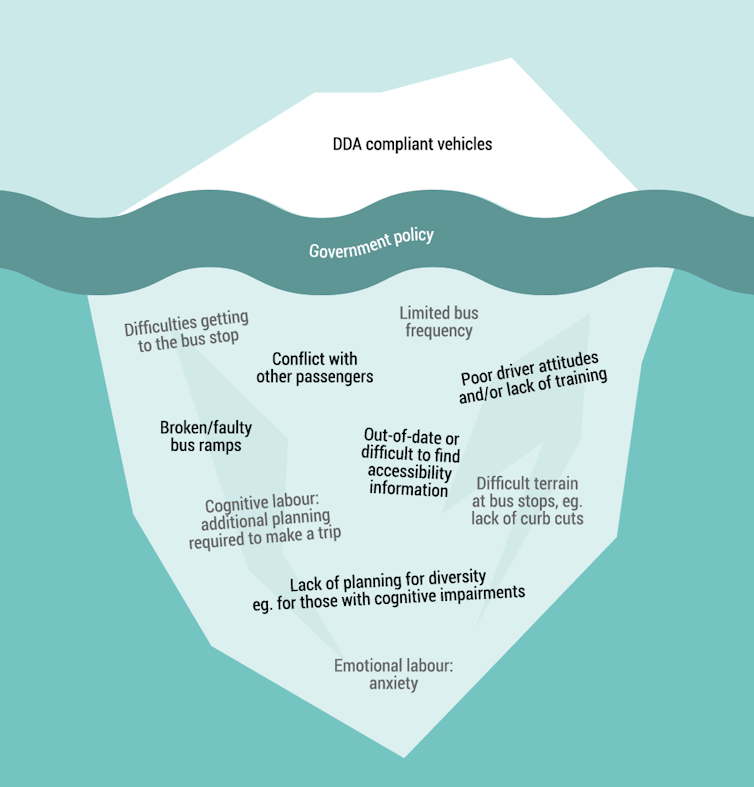

For buses, the standards largely focus on the vehicles themselves: low-floor buses, wheelchair ramps, priority seating, handrails and enough room to manoeuvre. But just because a vehicle is accessible doesn’t necessarily mean a bus journey is accessible.

There are difficulties getting to and from the bus, limited frequency of accessible services, poor driver training, passenger conflict, travel anxiety and a lack of planning for diversity. In all these ways, bus travel excludes people with disabilities.

Infrastructure alone cannot overcomes these issues. On-demand transport, which enables users to travel between any two points within a service zone whenever they want, offers potential solutions to some of these issues. It’s already operating in cities overseas and is being trialled in Australia.

Read more: 1 million rides and counting: on-demand services bring public transport to the suburbs

Accessible vehicles are just the start

Making vehicles accessible is really only the tip of the iceberg. Focusing only on infrastructure misses two key points:

our public transport journeys begin before we board the service and continue after we’ve left it

accessibility means providing people with quality transport experiences, not just access to resources.

Let’s imagine a typical suburban bus journey. It is industry accepted that passengers are generally willing to walk about 400 metres to a bus stop. That is based, of course, on the assumption that passengers are able-bodied. Long distances, steep hills, neglected pathways, few kerb cuts and poorly designed bus shelters all hinder individuals with disabilities from getting to the bus in the first place.

This issue resurfaced in the 2020 report People with Disability in Australia, by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. More than one in four respondents with disabilities said getting “to and from stops” was a major obstacle to using public transport.

But other barriers to making services inclusive are even more difficult to see. People with disabilities are forced to plan extensively when to travel, how to travel, who to travel with and what resources they need to complete the journey. Even the best-laid plans involve added emotional energy or “travel anxiety”.

Read more: Don't forget buses: six rules for improving city bus services

What solutions are there?

On-demand transport offers potential solutions to some of these issues. Its key feature is flexibility: users can travel between any two points within a service zone, whenever they want.

This flexibility can be harnessed to design more inclusive bus services. Without a fixed route or timetable, on-demand services can pick up passengers at their home and drop them directly at their destination. This door-to-door service eliminates the stressful journey to and from a bus stop and their destinations.

And with services available on demand, users can plan their travel to complement their daily activities instead of the availability of transport dictating their daily activities.

The technology behind on-demand transport also helps reduce the need for customers to consistently restate their mobility needs. Once a customer creates a profile, extra boarding and alighting time is automatically applied to all future bookings. This eliminates the exhaustive process of added planning, and enables drivers to deliver a better experience for all of their passengers.

Examples of on-demand services

Cities around the globe are already using on-demand services to overcome transport disadvantage for people with disabilities.

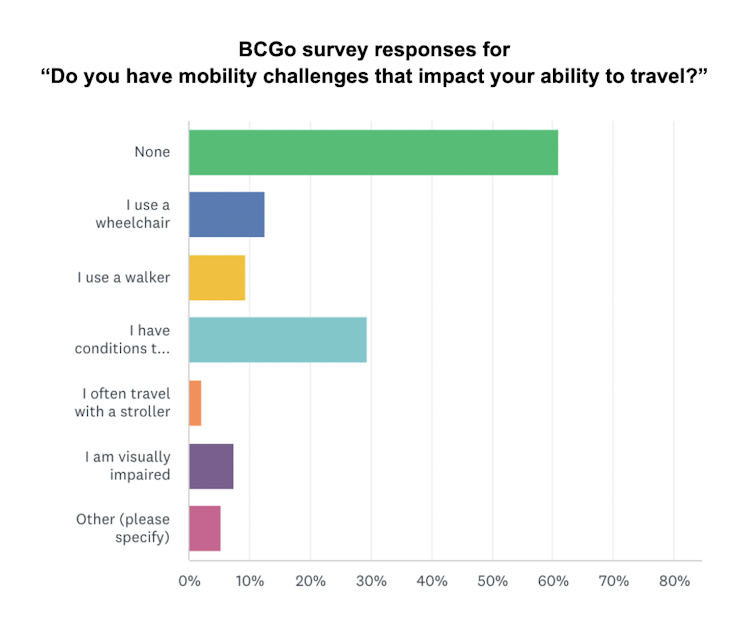

BCGo is one such service in Calhoun County, Michigan. A recent yet-to-be-published survey of BCGo users shows 51% of respondents face mobility challenges that affect their ability to travel.

Some 30% have “conditions which make it difficult to walk more than 200 feet” (61m). That means the industry’s assumed walkable distance (400m) is 6.5 times the distance that’s realistically possible for many users of the service.

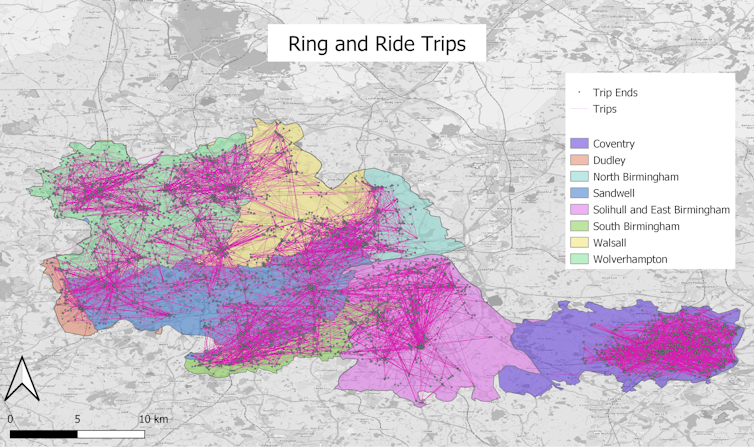

Ring & Ride West Midlands is the UK’s largest on-demand project. It operates across seven zones with over 80 vehicles.

The service, recently digitised using Liftango’s technology, is designed to provide low-cost, accessible transport. It can be used for commuting, visiting friends, shopping and leisure activities.

Ring & Ride serves as an example of how on-demand service can provide sustainable and equitable transport at scale. It’s completing over 12,000 trips per month.

Read more: What public transit can learn from Uber and Lyft

A call to action for Australian governments

Government policy needs to address not only inadequate bus infrastructure, but those invisible barriers that continue to exclude many people from bus travel. We need a cognitive shift to recognise accessibility is about creating quality experiences from door to destination for everyone.

This needs to be paired with a willingness to explore solutions like on-demand transport. Transport authorities worldwide are already embracing these solutions. We cannot continue to rely on the community transport sector to absorb the responsibility of providing transport for people with disabilities, particularly as our populations age.

Now is the time to have your say. The Transport Standards are open for public consultation until June 2023.

Read more: Eight simple changes to our neighbourhoods can help us age well

Ainsley Hughes is an Honorary Associate Lecturer in the Discipline of Geography at the University of Newcastle. She also works as a New Mobilities Specialist for Liftango.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.