“Nelson Mandela – I’d never heard the name before in my life,” a former prison guard to the South African icon recalls.

Christo Brand casts his mind back to 1978, and his first night guarding one of the most influential people of the past century. He was just 19 years old.

A sergeant informed him the ageing man sleeping uncomfortably on the floor of the Robben Island jail cell was “a terrorist trying to overthrow your country”.

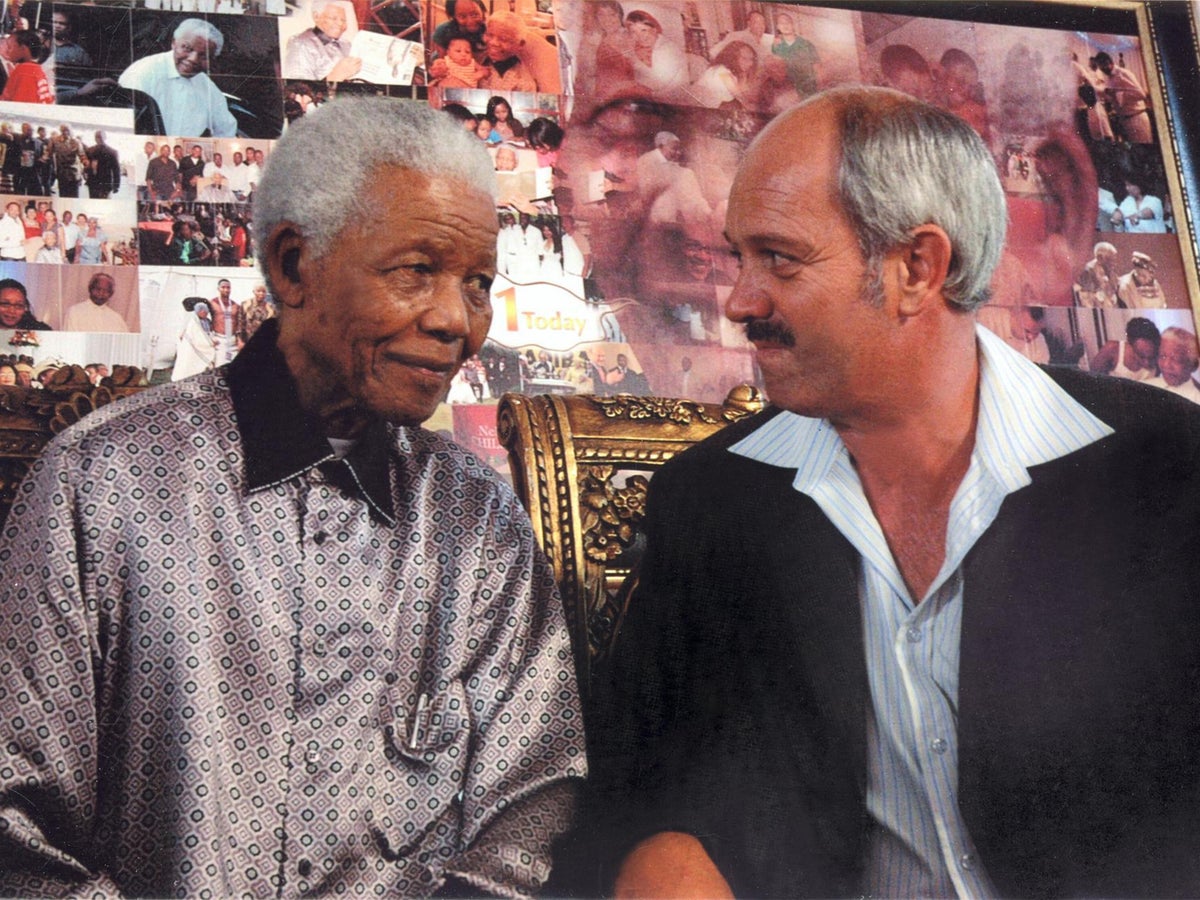

Mr Brand says he just felt sorry for the prisoner. He did not take much notice of the sergeant’s view and soon became close with Mandela; first as his guard, later working for him in government and, finally, attending his funeral as a family friend.

The young man grew up in the Afrikaans culture that dominated South Africa’s politics until Mandela’s election as the country’s first black president in 1994. The future leader had spent almost all of Mr Brand’s life to the day of their meeting in prison for fighting the established order.

In his childhood as a farmhand living two hours from Cape Town, Mr Brand saw little of the apartheid society that had driven Mr Mandela to radicalism. In his teenage years, he moved with his family to a segregated suburb of the city.

He was set, as were all white South African young men, for two years of military service until an older friend called up for action was killed, apparently by black activists.

Listening to a vicar eulogise his friend as a “hero” who gave his life for the struggle against the “black menace”, Mr Brand’s mind turned. The teen did not think his friend was a hero, nor did he think black South Africans were the enemy.

Mr Brand signed up for the prison service to exempt himself from conscription. Robben Island, the prison colony off the Cape Town shore where he was assigned, was mostly home to black men jailed for political reasons.

He began to spend days and nights with Mandela, who he says remained charming even after some 16 years as prisoner 466/64. In time he saw virtue in the older man’s crimes.

Reflecting after years at Mandela’s side, years in which he saw his friend slowly but surely topple the old order, Mr Brand says: “Mandela was fighting for the freedom of the country, he was prepared to go to the gallows for freedom for his people.

“Even when he was doing things that were wrong, he was doing things which were right for people of the time.”

The prison guard could also see how years in isolation had changed Mandela. In the days before his conviction the future president had started to view violent resistance as the only means of change in a society that had legislated to keep black people oppressed.

He received arms training on a trip around other African countries in 1962 but was arrested shortly after his return to South Africa for leaving the country without a permit.

“When Mandela was in prison,” Mr Brand says, “he studied Martin Luther King and Gandhi, he tried to follow their footsteps and try to bring a change.”

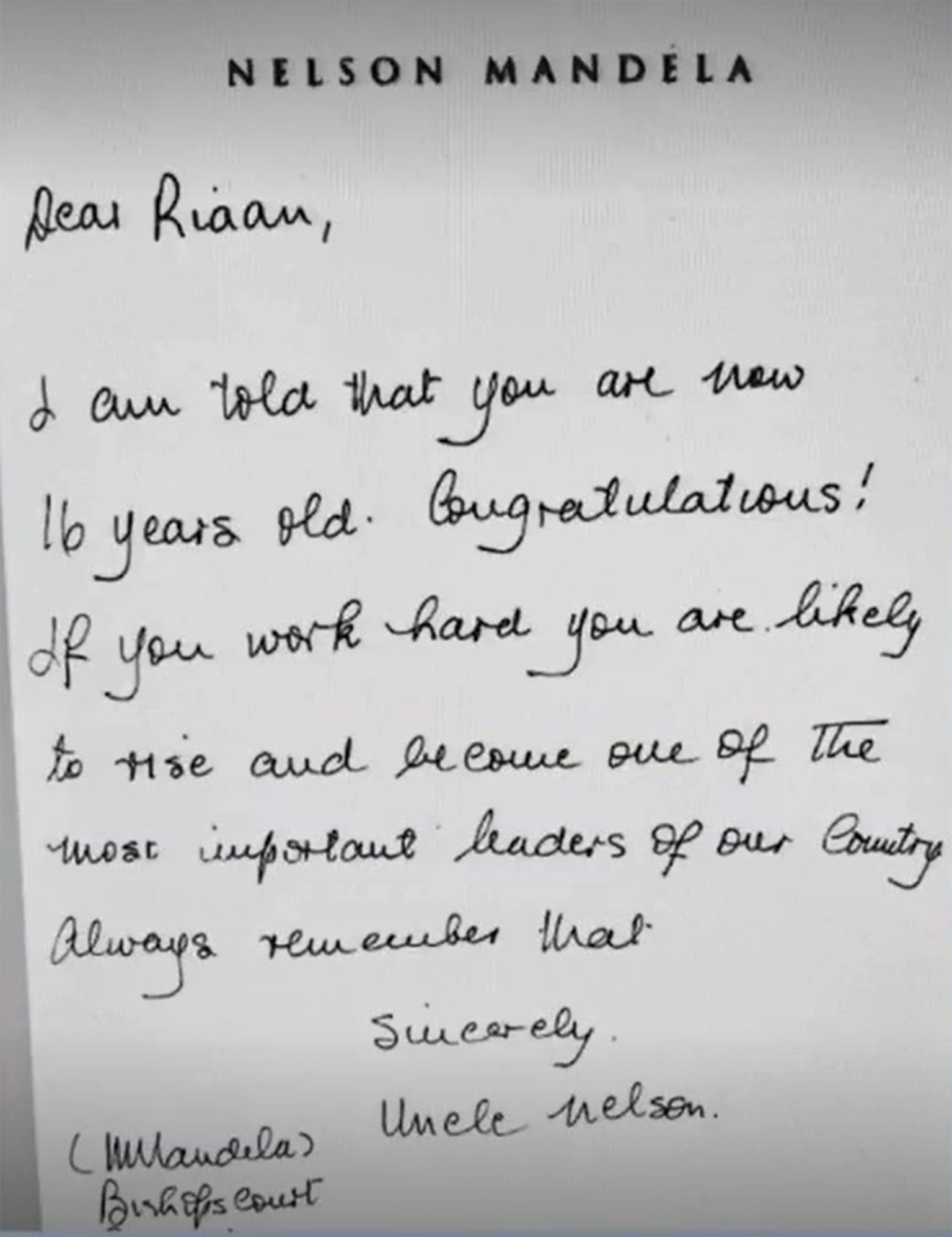

Mr Brand says that despite Mr Mandela’s occupation with the greater good he still took an interest in helping those close to him. As Mr Brand’s eldest son Riaan approached the end of school he complained to Mandela that the boy was ducking a university education in order to train as a commercial diver.

“Uncle Nelson”, who had written to Riaan to wish him a happy birthday, asked to speak to the boy privately. He told him not to let his father tell him what he could work hard at. Brand was eventually thankful.

In his memoir Long Walk to Freedom, Mandela hints at why he kept his prison officer at his side even after being freed. Mr Brand, he writes, “reinforced my belief in the essential humanity even of those who had kept me behind bars”.

Mandela emerged from prison in 1990 already negotiating with South Africa’s leadership for the changes that would see the country’s first democratic election a few years later.

He was an enormous global figure for the rest of his life, with leaders around the world taking pride in meeting him.

This year marks a decade since Mr Mandela’s death but, Mr Brand says, the leader’s spirit continues to thrive in the lessons he passed on. “People are still spreading his legacy. I try to tell his story [too],” he says.

Mr Brand, now retired, encourages prison officers to form bonds with those they guard. He works with Unlocked Graduates, a prison reform charity that seeks to stop prisoners from reoffending by building positive relationships behind bars.

To a young prison officer today, Mr Brand offers the moral that afforded him a seat at the side of one of modern history’s great figures: “You must treat your prisoners like a person.”

Click here for more information on the Unlocked Graduates scheme