Grieving the loss of a loved one is never simple – it can’t be. But it can be tougher for some people than others for lots of reasons. It will always be much harder to accept the death of a child that turns the order of life on its head than the loss of a grandparent. The circumstances of death – whether it was quick and painless, or long and debilitating – can also have an impact.

In her 1969 book, On Death and Dying, Swiss-American psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross described five stages of grief: denial and isolation, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance.

Since then, others have suggested that the stages should be referred to as states, since a grieving person may not experience all of them, and in no particular order. Other states have been put forward, including shock and testing, which usually come before acceptance, and reverie and revival – in which the memory of the lost one is elevated and cherished while the rest of life goes on.

Death Cafés, open forums to talk about mortality, spurred by Covid-19

Grief isn’t linear: you may be unable to function one day and the next you might manage to laugh at lunch with friends. And it manifests in a million different ways in a million different people. Grief is messy, even when it’s anticipated, even when you understood you were going to lose a loved one.

While grieving is difficult, it is a normal and natural reaction to loss, says Dr Andrew Stock, clinical psychologist and president of the Psychotherapy Society of Hong Kong. We’re all going to die, so we accept death, reluctantly, as a constant in our ever changing world. But we need a name, an added descriptor to use, when grief unfolds in a less healthy way, he says.

In psychiatry, the clinical term used to identify complicated grief is persistent complex bereavement disorder, assigned to those who are significantly and functionally impaired by prolonged grief symptoms. How would you know, though, if somebody was suffering from complicated grief?

One of the first signs, Stock says, is that a grieving person’s life “seems to be getting smaller, shrinking” as people withdraw from interacting with the world, as they avoid memories.

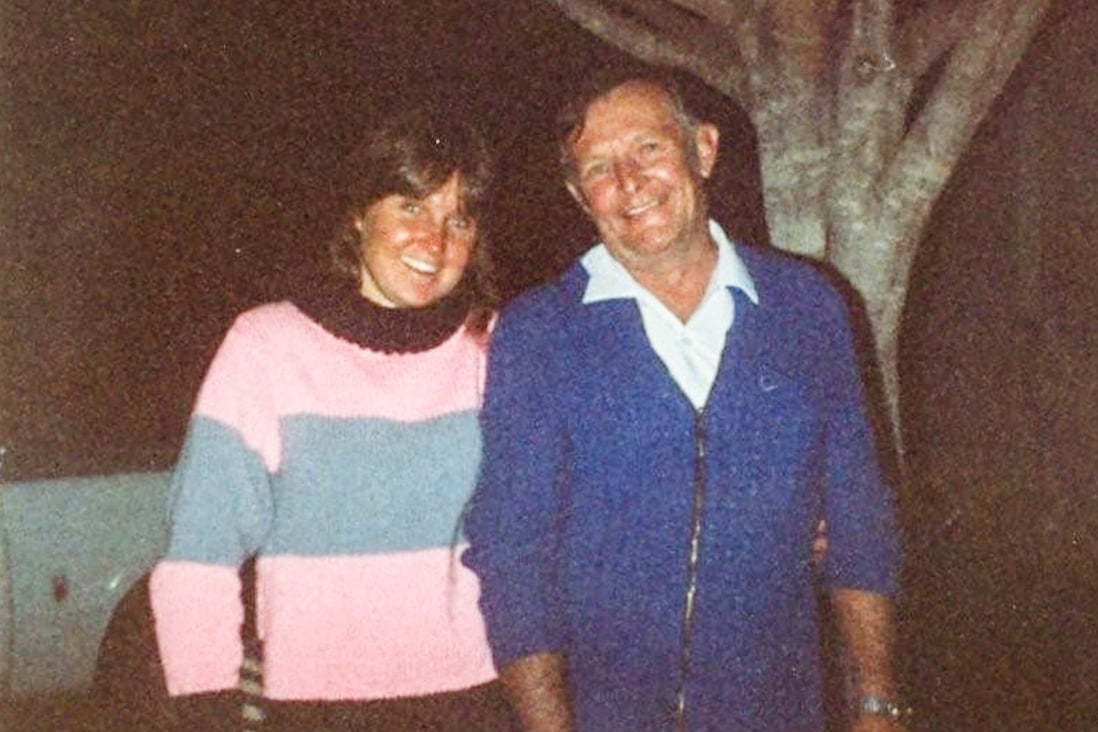

After my own father died – aged 47 in a car accident in 1985 – my mother moved her children halfway across the world. There was no trying to avoid the people and places we associated with dad; they weren’t in our lives any more, either. Perhaps that protected us from some measure of our grief. But at the same time, it withdrew valuable resources that we, and especially she, may have found useful as we reeled in the aftermath of dad’s death.

As Stock explains, how a person manages grief largely depends on the resources, internal and external, that the bereaved can draw upon.

Despite not having to bump up against reminders of an old life, I began to suffer horrendous nightmares in which I dreamed my father was alive but broken in a rehabilitation facility, or that we were trying to peel him from the wreckage, or that he had simply vanished from our lives and reappeared as this damaged man years later.

The dreams were deeply unsettling. Stock agrees these horrid dreams could have been a manifestation of a grief that was not resolved.

Belinda Lau, a counsellor and psychotherapist at The Lighthouse Counselling in Hong Kong, says grief and loss are among the most challenging issues to work through in therapy sessions. “The emotions can be so complicated and quite often clients are not able to elaborate. The most common pain that the bereaved experience is the self-blame and guilt that they could have done more,” she says, or that they could have done something differently.

I didn’t experience self-blame and guilt, but I contemplated plenty of “what-ifs” and “if-onlys”. And I didn’t seek the support of a therapist until decades after dad died. When I finally did, I felt ridiculous admitting that he had died 20 years ago. “For some reason all that sadness seems to have bubbled back up,” I mumbled.

The therapist I spoke to said it was not uncommon for grief to rear up long after a loss. For it to happen at my age, then, may have meant I was seeking a connection with the people my parents had been.

What of the dreams, I asked, ashamed that they could have been the product of an unwholesome and morbid fascination. They were not, the therapist assured me, and the relief of being told this was profound. Rather, they were the unconscious fabrication of an ending that was less painful, less final, than the reality; a scenario woven in my subconscious from the chaotic emotions and change wrought by sudden death.

She left her grief and guilt behind by climbing volcanoes

Stock says that my age at the time, 19, and the sudden and tragic circumstances of dad’s death may well have complicated my grief. That and the fact that, when the sadness overwhelmed all over again, my husband was nearing the age my father had been when he died.

“A parallel experience in another relationship can trigger unprocessed emotion,” Stock says.

But as Lau reminds me, grief is the emotional reaction to all loss, “not only loss that manifests through the death of a loved one, but also the loss that comes with the ending of an important relationship, say, or a career, or even a certain lifestyle or sense of self that no longer seemed retrievable. People often cope then by dissociating themselves, denying their thoughts or displacing onto somewhere else, forming a complicated grief” – and perhaps shrinking their lives a little.

The American writer Ted Bowman considered children especially vulnerable to “disenfranchised grief”, which he associated with the “shattering of dreams”. He described this as “the loss of an emotionally important image of oneself, one’s family or one’s situation; the loss of what might have been; abandonment of plans for a particular future; the dying of dreams”.

This fits. I didn’t just grieve mine and dad’s history, our past, the years we’d had. I had to grieve the future we never had – the joint 50th and 21st birthday party we’d planned which never happened. I grieved what should have been.

And, 20 years after the fact, I did something I should have done, or been encouraged to do, at the time: I sought professional help in untangling my grief. It was quite extraordinary. I wish I’d done it years before. After just three conversations, I felt as if this burden had been lifted, as if I had been allowed to let something go.

And my nightmares stopped, just like that. They stopped.