Most people recognise organisations such as the YMCA and the Boy Scouts, or events such as the Modern Olympic Games, summer camps and wilderness retreats.

Few, though, have ever heard of the movement from which they took their principal inspiration: muscular Christianity.

The term sounds odd indeed, conjuring up images of Jesus with an impressively chiselled physique or, for devotees of the eighties, Vangelis’ memorable soundtrack to Chariots of Fire.

However, the term arose because it once carried Christian hopes of a solution to a longstanding problem: men.

That is, in the 19th century especially, Christian churches became particularly alarmed more and more men were leaving religion to women – from attendance at worship to running parish organisations or establishing charitable endeavours.

Worse still was the fear Christianity itself had become soft and even effeminate through the Victorian age.

Christians, especially the Protestants who started the movement, needed to present Christianity in ways attractive to men. But how?

A literary beginning

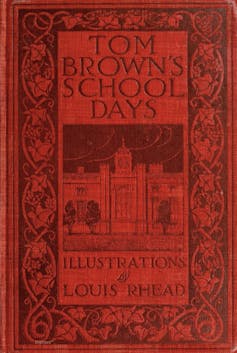

In 1857, the Englishman Thomas Hughes published the novel Tom Brown’s School Days, followed later by Tom Brown at Oxford in 1859.

In the first book, Tom attends the prestigious Rugby School, before making his way to Oxford in the sequel. This character would epitomise a “muscular Christian”, as Hughes put it. In the sequel, Hughes wrote:

The least of the muscular Christians has hold of the old chivalrous and Christian belief, that a man’s body is given him to be trained and brought into subjection, and then used for the protection of the weak, the advancement of all righteous causes, and the subduing of the earth which God has given to the children of men.

Men precisely as men could use their bodies to Christianise the world. A movement with twin aims was born: first, encourage men to embrace their physicality and second, through such disciplining of their bodies, to glorify God.

Rise and fall

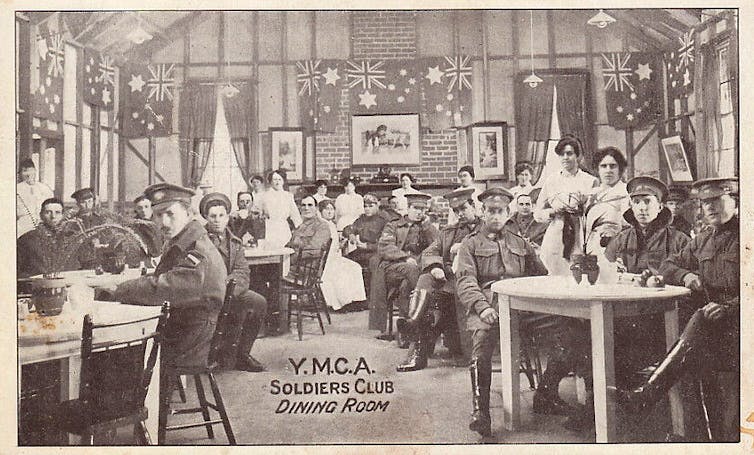

From England, the movement spread through the Anglosphere, including Australia.

And it has some impressive credentials. Pierre de Coubertin’s inspiration for reviving the Olympic Games was, in part, inspired by reading Tom Brown’s School Days.

In the United States, the YMCA – the Young Men’s Christian Association – in New York added a gymnasium in 1869, which soon became a permanent fixture at the “Y.” The physical director at Boston’s Y coined the term “body building”. James Naismith would later invent basketball in 1891 while working at a Y.

Many Protestant churches drew upon muscular Christianity to bring men back into the fold. They masculinised church services through hymns which celebrated manliness and virtue, encouraged ministers to embody more masculine traits, brought men into the company of other men through brotherhoods and promoted vigorous missionary activity.

Even Jesus received a makeover – arguably the most popular being Warner Sallman’s 1940 portrait painting Head of Christ.

Sallman’s original motivation for such depictions came from the dean of a Chicago Bible College in 1914:

I hope you can give us your conception of Christ. And I hope it’s a manly one. Most of our pictures today are too effeminate.

There is evidence, too, of Catholics muscling in. Take, for example, Notre Dame’s football team’s successes in the 1920s and 30s in the US, or the Italian cyclist Gino Bartali, winner of the Tour de France in 1938 and 1948 and, according to the Catholic press, the ideal Catholic sportsman.

Most historians will mark the decline of the movement after the first world war, though its influence continues to be felt to this day.

A continuing legacy?

So, apart from indulging in historical curiosity, what does it offer us?

Muscular Christianity highlights both the dangers and continuing challenges raised when navigating the complex relationship between religion, culture and gender.

It pursued a worthy goal, but tended to play a zero-sum gender game: gains for men in the churches often came at the expense of women. Such emphasis on masculinity easily slipped into gender bias, where a “church full of men” was deemed more valuable than churches full of women.

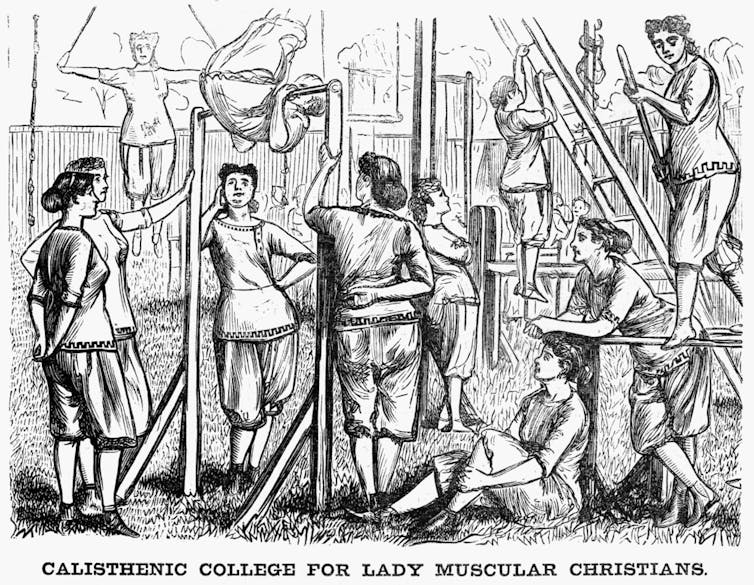

The effort to bolster masculinity also traded in narrow gender stereotypes, though as the historian Clifford Putney reminds us, there was some flow-on effect for women and their organisational engagement in sport and physical activity.

Some evangelical Christians have recently re-engaged its ethos.

And perhaps muscular Christianity still has something valuable to say. At the very least, scratch beneath the surface of modern Western culture and you will often find Christianity or values which originated from it.

Muscular Christianity can also remind us to reconnect with our bodies. We now live in a world which, as Australian author Michael Frost argues, has become increasingly “excarnate” – that is, less bodily.

Muscular Christianity recognised bodies matter and matter spiritually. It encouraged people not to treat health and physical activity as ends in their own right or as a servant of the ego but, rather, a means to an end: wholeness, good character, the cultivation of virtue and the selfless desire to help others.

Gavin Brown does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.