THERE was a time when people thought that a secular, democratic Turkey would eventually accede to the European Union and join the club of wealthy liberal states known as the West. There was a time, too, a few years ago, when Turkey was a darling of emerging-market investors.

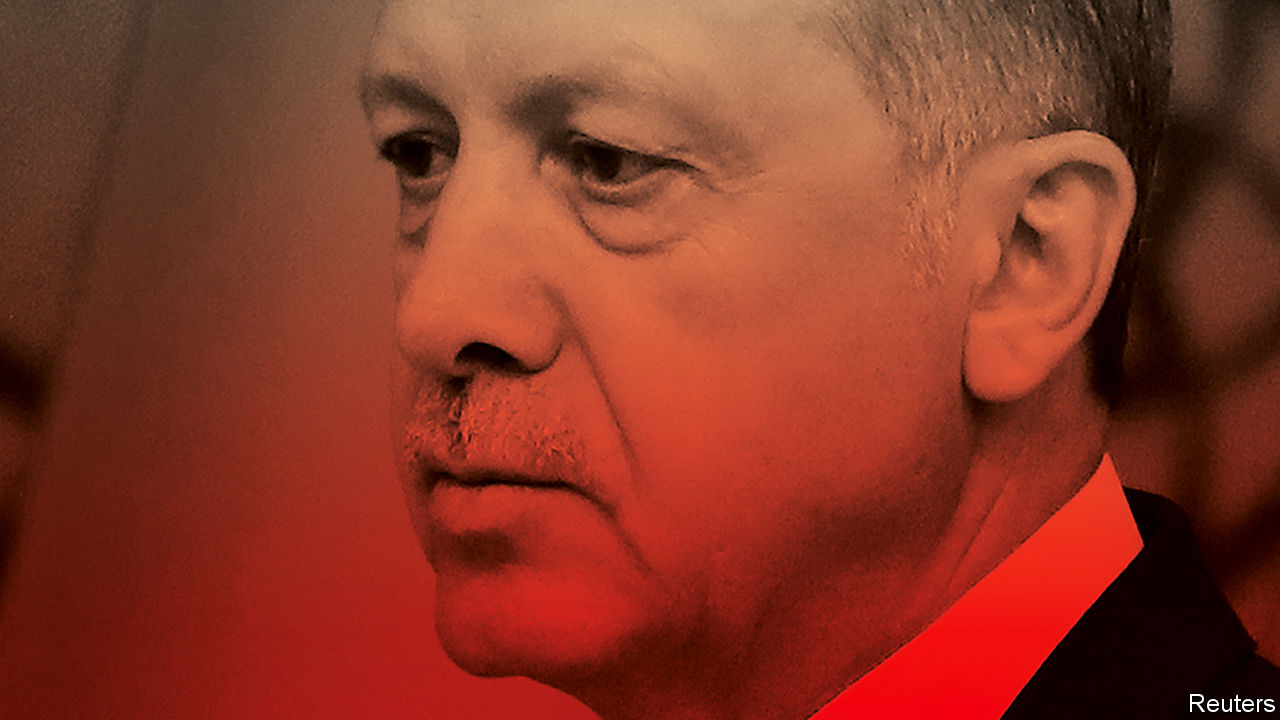

Those days are long gone. Politically, the country has been tilting away from the West for years: becoming more stridently Islamist, picking fights with NATO allies and transforming itself into a virtual autocracy under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Economic-policy orthodoxy has been junked. High growth rates have depended on foreign borrowing: the amount of corporate foreign-currency debt has more than doubled since 2009. Mr Erdogan, who believes that high interest rates magically cause inflation rather than cure it, has stopped the central bank from acting sensibly.

Both these trends have now come to a head. Turkey is gripped by a currency crisis, precipitated partly by America’s imposition of sanctions over Mr Erdogan’s refusal to release a pastor, Andrew Brunson, who is absurdly accused of terrorism. President Donald Trump has made matters worse by vowing to slap higher tariffs on Turkish metals. The lira has lost a fifth of its value this month, further fuelling inflation, increasing the burden of foreign-currency debts and threatening the health of Turkey’s banking system. Relations with America are poisonous. Mr Erdogan blames Turkey’s economic problems on a plot by foreign enemies and has imposed retaliatory tariffs on American cars, alcohol and even cosmetics.

The crisis poses three types of risks: for other emerging markets, nervous that investors will flee as contagion spreads; for Turkey’s economy, which is staring at a deep recession; and for the West, whose fraying bonds to Turkey could finally break. On each count, how bad could things get?

When Erdogan sneezes

Start with the least-bad news. The lira’s collapse has caused wobbles in other emerging markets that may share one or more of Turkey’s traits, including an inadequate savings rate, a big current-account deficit, lots of foreign-currency debt and high inflation. The South African rand swooned; the Indian rupee hit a record low this week; Argentina, which has already had its own currency crisis this year, raised interest rates again. Shares in banks with exposure to Turkish borrowers fell (see Finance section).

The environment for emerging markets has become less forgiving as the tightening of monetary policy in America has boosted the dollar and as concerns grow about China’s economy. But a cascade of currency crises still seems unlikely, mainly because Turkey’s frailties are so acute. Of the big emerging-market economies, only Argentina and Egypt (both now wards of the IMF) also have a double-digit inflation rate; none has a current-account deficit as big, although Pakistan’s comes close. Other markets have more room for policy manoeuvre. And the ones with problems that are most similar have shown more alacrity in tackling them. The fact that Argentina’s central bank acted to raise interest rates is a source of comfort.

For Turkey itself, there is a fairly standard blueprint to follow when an economy gets into such straits: raise rates to reduce pressure on the currency and tackle inflation, and seek out emergency financing from the IMF, tied to a set of investor-friendly policies. Argentina did just that earlier this summer, helping to nip its crisis in the bud.

Turkey has so far done little more than fire-fight, offering some help to the banking system, making it harder to speculate against the lira and drumming up promises of investment from allies such as Qatar, which will provide dollars but not credibility. Mr Erdogan’s resistance to higher interest rates, and the fact that turning to the IMF would require some bowing and scraping to America, dent the chances that Turkey will get ahead of things. That could be the difference between a managed adjustment and a chaotic collapse, in which defaults spread and banks teeter.

He blames America

Mr Erdogan may yet see sense. But his autocratic style fosters bad policies. He has undermined the institutions that ought to stand up to him. The central bank, which should be independent and technocratic, defers to a leader with crackpot views. The finance ministry is run by the president’s son-in-law. The media, which should be pointing out Mr Erdogan’s mistakes, are so cowed that they repeat his conspiracy theories instead. Deprived of real news, many Turks believe their problems are caused by a Western plot. With no one to curb him, Mr Erdogan is free to indulge his worst instincts.

In normal times, Turkey’s Western allies might help by telling Mr Erdogan to change course. But European governments are scared to upset him, lest he open the gates and let Syrian refugees flood into Europe. And Mr Trump is engaged in a ridiculous chest-thumping contest with the Turkish leader, with each man trading threats and stirring up patriotic anger against the other. Neither is willing to back down, for fear of looking weak.

In the short run Turks will suffer far more from the crisis. Many are already feeling poorer as prices soar. In the long run, however, America will suffer, too. Turkey is an important ally in a crucial place, straddling the crossroads between Europe, the Middle East and Asia. If it falls out too badly with the West, it may drift even closer to Russia or China. Mr Trump is right to press for the release of Mr Brunson, but wrong to use tariffs to that end. The rules-based trading system depends on countries not using such blunt weapons indiscriminately. And the NATO alliance is undermined when America’s president needlessly inflames disputes with tetchy member states.

Mr Trump and Mr Erdogan need to find a face-saving way for each to declare victory and dial down the aggression, as Mr Erdogan has previously done with Russia and Mr Trump with North Korea. That would create room for the West, including the IMF, to help Turkey step back from the abyss. It will be hard to save a country whose leader does not understand why it is in trouble. But Turkey is too important to be abandoned.