In the acknowledgments of her 2024 novel “All Fours,” Miranda July explains that she was inspired by a series of conversations about “physical and emotional midlife changes” with several women close to her.

“And while there is almost no trace of these actual conversations in the book,” she adds, “they made writing it more necessary.”

The novel finds a middle-aged mother choosing to leave home and drive across the country in search of herself. Sound a little hackneyed? Maybe that’s why she gives up after about 30 minutes, pulling into a dingy motel and instead trying to turn back time from her new home base, the appropriately chosen Room 321.

In this bland environment she undergoes a physical and spiritual awakening – a dance to the Muzak of time. Whether remodeling her motel room or defying libidinal decline with a nearby Hertz rental car employee, July’s protagonist, who talks a lot about respiration – “I breathed in; I breathed out” – finally breathes life back into herself.

Along the way, “All Fours” frames middle age as something that must be felt and communicated afresh, one powerful, awkward, minutely recorded sensation at a time.

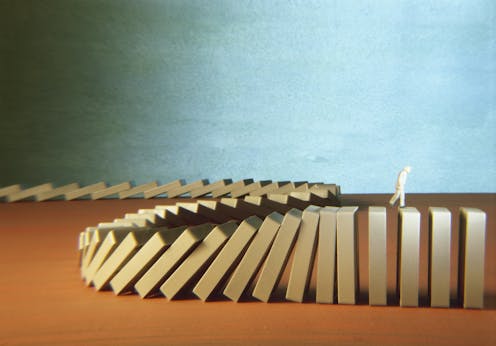

Easier said than done. Some clichés are like planets, their gravitational pull too strong for all but the most propulsive acts of creativity. Middle age is one of these. The changes often associated with being in your 40s and 50s – gray hairs, career doldrums, time’s squeaky-wheeled chariot drawing near – can seem as inevitable as aging itself.

And yet, as my research on the construction and representation of aging has shown, the middle years aren’t what they used to be, nor what they will one day become.

Inventing midlife

The history of middle age begins as far back as the eye can read.

In classical Western literature, the middle of life is represented as a time to live and die magnificently.

In the Greek epics, Odysseus and Ajax – are middle-aged, and neither loses sleep wondering about his life choices or whether his skills are falling off. Nor does Homer worry much about conveying how these men became who they are. Wily Odysseus, you can only assume, was wily pretty much from the cradle.

Beowulf, the hero of an early Anglo-Saxon poem, likewise does not show signs of slowing down until old age, when a dragon proves too much for him to kill without help from a much younger man. Embarrassing.

The middle phase of life, these works imply, is the time when people are most themselves, with the greatest abundance of skill and purpose that life will ever confer.

Even Shakespeare saw midlife as little cause for anxiety. Among the “seven ages of man” described in “As You Like It,” middle age corresponds roughly to the part of “the justice,” a man with “fair round belly” and “wise saws” who sounds a little quaint, perhaps, but also content; it is only during the sixth age, with the approach of what Shakespeare calls “second childishness,” that a major shift occurs and quality of life starts to drop.

The birth of crisis

Then everything changed. The Industrial Revolution gave rise to a new bourgeois class that, when not reeling from the latest market crash, had time and money to burn.

Middle-class leisure, unlike the aristocratic kind that greeted one at birth, required shifting gears, from a full-steam-ahead search for one’s place in the world to the relative stagnancy that came with having found it.

This kind of whiplash was enough to make a crisis of midlife: a deep-seated feeling of anxiety about the value of one’s achievements, the meaning of existence and the proximity of death.

While the actual term “midlife crisis” was not born until 1965, thanks to 48-year-old Canadian psychoanalyst Elliot Jacques, its gestation stretched across the 18th and 19th centuries. Romantic poets such as John Keats and Percy Shelley, who died at 25 and 29, respectively, taught readers to covet the summer of life with almost desperate intensity, and even a slight chill in the air became cause for dread.

The Victorians, perhaps sensing that Britain’s empire could not stay young and virile forever, took this Romantic dread and ran with it. In the 1853 novel “Little Dorrit,” 41-year-old Charles Dickens portrays 41-year-old Arthur Clennam, who gloomily meditates on what he’s done with himself and how little it’s gotten him:

“‘From the unhappy suppression of my youngest days, through the rigid and unloving home that followed them, through my departure, my long exile, my return, my mother’s welcome, my intercourse with her since, down to the afternoon of this day with poor Flora,’ said Arthur Clennam, ‘what have I found!’”

For Clennam, a jaded merchant who recently vacated his position with the family firm in search of some greater purpose, taking stock of one’s life seems a painful but necessary exercise. He also takes another kind of stock, investing in a Ponzi scheme that plunges him, with most of London, into a state of financial crisis that mirrors his personal one.

A generation later, in the U.S., Theodore Dreiser’s 1900 novel “Sister Carrie” tells the story of George Hurstwood, a successful businessman whose life begins to unravel the moment he stops working long enough to question its real worth.

Both Clennam and Hurstwood eventually take up with a 20-something woman – one finding regeneration in that relationship, the other dishevelment and death.

In another time, both men might also splurge on a red Corvette.

Future midlife

What about middle-aged women in the 19th century?

In a way, there were none. The critic Sari Edelstein, in her 2019 book “Adulthood and Other Fictions,” encourages readers to think about adulthood not as a biological fact but as a cluster of political rights and privileges conferred on some people in the U.S. – usually white men – and largely withheld from others, such as women and people of color.

While race, class and marital status profoundly impacted women’s experience of midlife, one fact remains constant for much of the century: the absence of full adult status under the law. Even as they matured, women were kept little.

They were also portrayed as such. Popular novels such as “The Lamplighter” and “The Wide, Wide World” retraced time and again the approved boundaries of a married woman’s life, which extend no further than the home. Unmarried women and widows could hold property and manage their own financial affairs, but the period literature far too seldom represents their point of view. Not until the advent of second-wave feminism, and works such as Doris Lessing’s 1974 novel “The Summer Before the Dark,” did middle-aged womanhood become a topic more openly and creatively explored on paper.

For all that creative labor across the past century, the English-speaking world has been largely resigned to the idea of middle age as a dreadful, isolating crisis.

This is likely due in part to the midlife crisis’s amazing elasticity – the way it stretches to accommodate shifting cultural contexts and the rise of whole new artistic forms. Few other topics seem to lend themselves so generously to esoteric offerings and crowd-pleasing genre fare, to the page and the screen. (For my money, one of the best films about midlife crises is Martin Scorsese’s “Casino.”)

If not a crisis, what else could midlife be?

Perhaps the gateway to something universal.

While the narrator of “All Fours” suffers plenty of distress and ennui, she never uses the word “crisis” without scare quotes. She’s clearly holding out for another kind of midlife.

That faith is rewarded in the last chapter, when she watches a dance recital and feels the “warm, hallowed feeling” from her hotel retreat “gilding the whole neighborhood, the whole city … The whole universe? Yes…”

She reflects: “If 321 was everywhere then every day was Wednesday, and I could always be how I was in the room. Imperfect, ungendered, game, unashamed. I had everything I needed in my pockets, a full soul.”

Her consciousness expanding and contracting between the scale of the universe and that of her own pockets, July’s narrator does more than regenerate. Rising and falling, part St. Teresa and part Lady Macbeth, she embraces both the ecstasy and the tragedy of life and is twice empowered.

It is a midlife metamorphosis.

This article has been updated to remove a characterization of Achilles as middle-aged.

Matthew Redmond does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.